New York’s downtown in Dan Colen’s and Dash Snow’s ‘nests’

by Grace Linden • June 2020

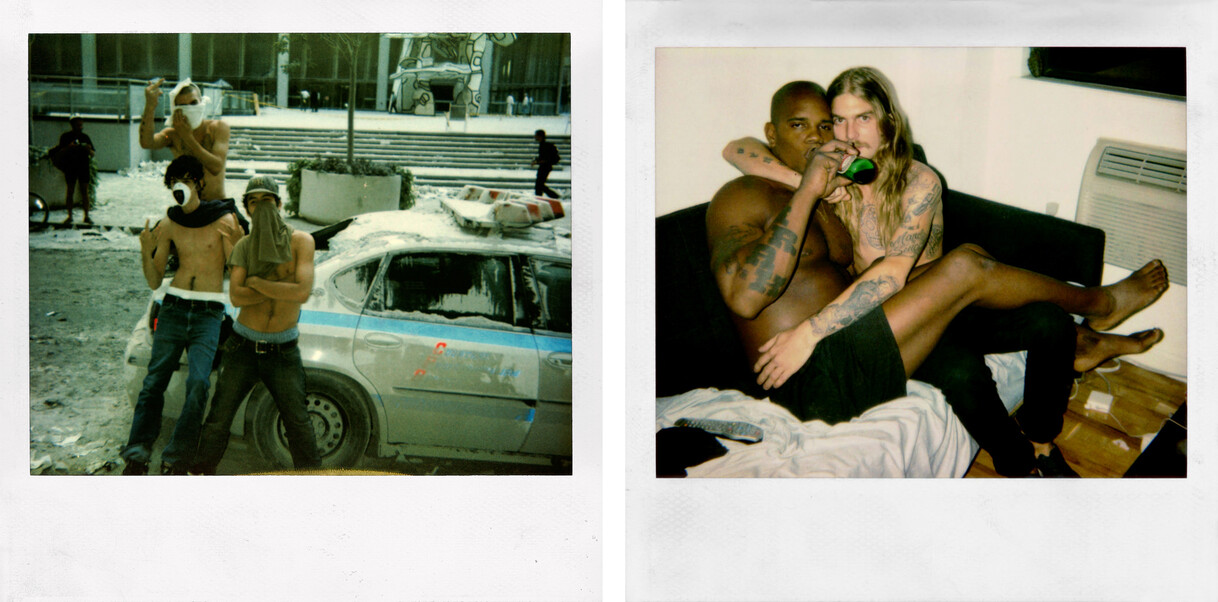

In the early days of their friendship Dan Colen and Dash Snow created immersive spaces that they called hamster nests. Initially these were private rituals that took place in hotel rooms where, fuelled by drugs and alcohol, Colen (b.1979) and Snow (1981–2009) would tear at the curtains and sheets, rip up any paper materials they could find and roll around in the wreckage like hamsters in a cage. As with the notorious havoc wreaked by celebrities such as Keith Moon and Keith Richards, by the end the rooms were wholly destroyed, a mess of papers, rubbish, spilled beer and bedding. The first nest occurred in 2003, and others soon followed: on a road trip from New York to Miami; in Los Angeles one New Year’s Eve; and in a hotel room in London paid for by the art dealer Charles Saatchi. The nests were haphazardly documented by Snow or sometimes by their friend Ryan McGinley, who, in 2016, posted a photograph on his Instagram account from a nest created in 2004 FIG. 1. The image shows a room thoroughly destroyed, where specks of paper glint like reflections in a disco ball. Snow, doubled in the mirror’s reflection, looks feral and leonine.

Stories circulating the art world about the nests seemed to verify claims of Colen’s and Snow’s ‘bad-boy’ tendencies.1 ‘The nests’, reflected Colen, ‘were all about wanting to invent a new place [where] only your rule is relevant’.2 Both his and Snow’s developing practices were suffused with a sense of hedonistic autonomy, a forceful focus inward that informed both their aesthetics and their lifestyles.

Colen met Snow when he was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). They quickly became synonymous with New York City’s ‘downtown’ art scene emerging in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks in 2001, a group of tightknit friends who mined their physical environment and social networks to produce an art of and about their lives.

During this period Colen predominantly created hyper-detailed oil paintings, while Snow embraced a variety of materials – although he remains primarily known for his series of semi-candid Polaroids featuring his friends and the city FIG. 2. Born in Manhattan, Snow was a descendant of the de Menils, whose immense art collection formed the basis of what is now the De Menil Collection, Houston. Even so, Snow is often described as having ‘stumbled’ into art, a reluctant artist averse to the drama and wealth he witnessed as a child.3 To be able to stumble into a career, however, suggests a degree of economic and social privilege, the same privilege that enables one to trash a hotel room and exit not just unscathed but buoyed.

Life downtown

On paper, there existed little overlap between Colen’s and Snow’s practices, but they both shrewdly defined themselves as New York artists rooted in the downtown community, allying themselves with a specific vision of the city. Downtown New York has long been mythologised as ‘avant-garde terrain’, and a central aim of this article is to examine the use of this legacy by Colen and Snow in the nests and their wider careers.4 This construction dates to the 1960s, when artists and writers relocated to Greenwich Village for its mix of eccentricity, history and multiculturalism. As Sally Baines explains:

In the early Sixties, when New York City was undergoing massive demolitions, reforms, and building construction, Greenwich Village was acutely conscious of its historical character in a number of respects: as an elegant landmark district, as a bohemia, and as an ethnic neighbourhood. Indeed, it was self-consciously a steadfast village, with several interwoven histories, that its residents thought managed (partly through long-standing geographic isolation) to preserve the warmth of face-to-face, “authentic” experience in the midst of escalating metropolitan anonymity.5

This ‘authentic’ historical character became the bedrock of the downtown and lay the foundations for the city’s countercultural movements of the 1970s and 1980s.6 The area had cultivated a bohemian image since the mid-nineteenth century, when artists and intellectuals including Mark Twain, Winslow Homer and Walt Whitman moved to the neighbourhood. Home to one of the country’s oldest free Black settlements since the seventeenth century, the Village had long encouraged and attracted diversity of all forms. The opening of the Cherry Lane Theater in 1925 and the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931 further cemented the district’s identity. By the 1960s Greenwich Village was ‘acutely conscious’ of its bohemian heritage.7

Later histories of the downtown, which expand beyond the Village to include the whole of lower Manhattan, exploited understandings of the area as a ‘historic mecca’ for bohemians.8 Within the art world, such language is particularly tied to SoHo, where artists flocked in the 1960s to occupy the glut of cheap and abandoned real estate marked for demolition by the city to make room for a planned Lower Manhattan Expressway. (The name SoHo, which stands for South of Houston, came into use only after the artists had already transformed the neighbourhood.)9 Inside the lofts a vibrant cultural sector emerged, and dealers and gallerists soon followed. SoHo’s renaissance, however, led to rising rents; first came the luxury boutiques and restaurants, then wealthier professionals, all of which proved more profitable for landlords than art.10

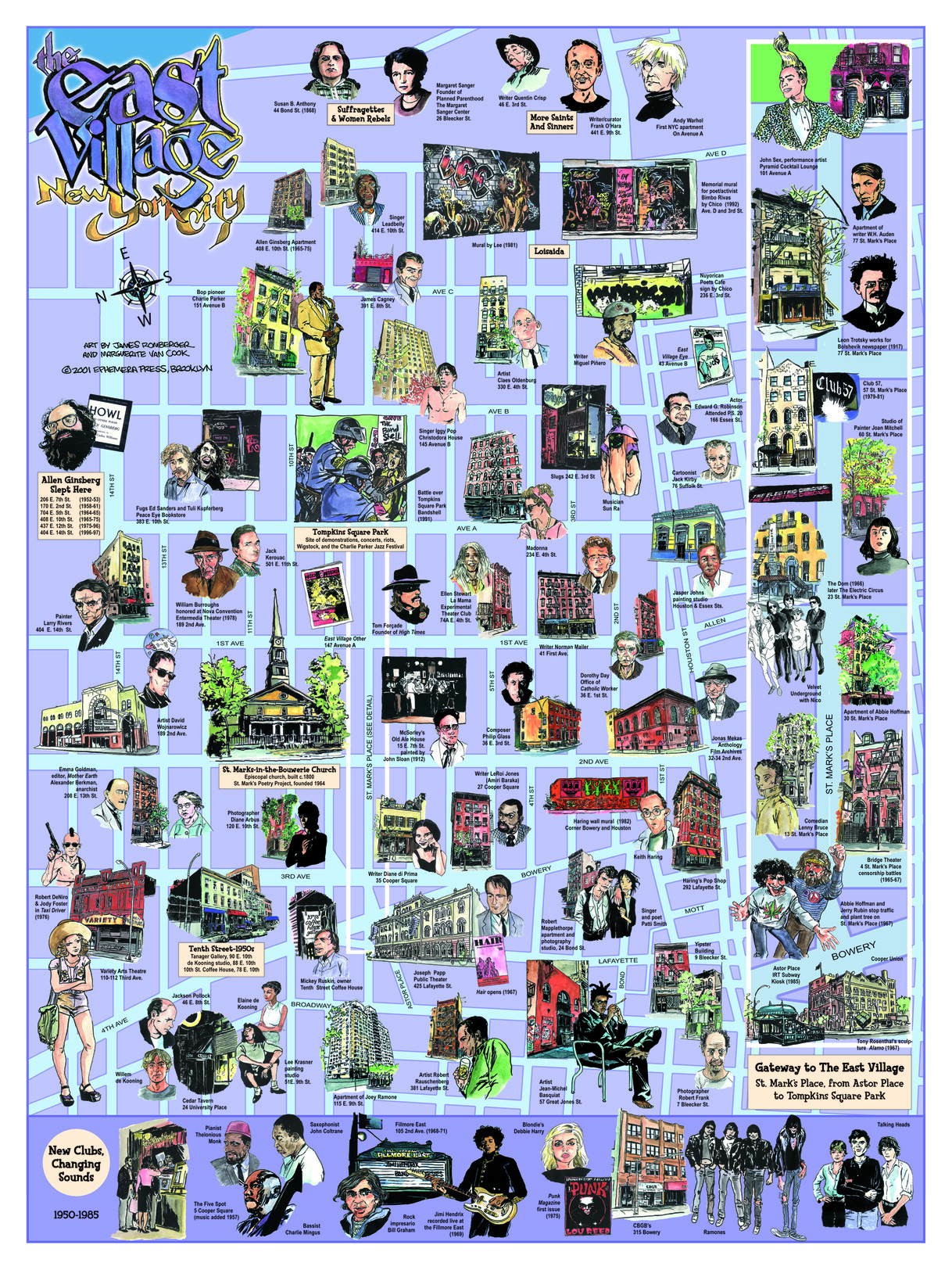

The idea of a downtown bohemia can be seen in and is reinforced by the representation of certain cultural figures. Sylvère Lotringer’s and Giancarlo Ambrosino’s biography of David Wojnarowicz (1954–92), for example, also functions as an urban oral history.11 In interviews, Wojnarowicz’s friends, partners, and collaborators discuss their relationships to the artist vis-à-vis the landmarks of their New York. By grounding their stories in the downtown neighbourhoods, the memories shared become contingent upon an engagement with the city itself. The already entangled relationship between the city and its inhabitants is brought to the fore and further emphasised by the book’s endpapers, which reproduce a map extending from the Village through SoHo and the East Village FIG. 3. The illustration is annotated with sketches of famous addresses and figures including Keith Haring’s Pop Shop, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s studio on Great Jones Street and Madonna’s apartment. Downtown, this map says, is for artists; downtown is the place where creative history is made and lived. The concentration of artist figures gave these districts a ‘distinctive appeal’ that was ‘intensely cool, identifiably local and ethnically diverse’.12 Yet by the time Colen and Snow were looking to launch their careers, that iteration of the art world no longer existed (if it ever did in the way that it has been presented retrospectively). A place’s cultural history is necessarily tied to its geography, but such a relationship can also lack nuance. If Lotringer’s map makes visible the district’s creative networks it also flattens the city’s many, and often divergent, layers.

By the early 2000s SoHo had become populated with luxury shops and restaurants. The East Village, home to immigrant populations and an explosive but short-lived art scene during the 1980s, saw its real estate skyrocket in the following decade; in 2000, the average rent for a studio apartment was above $1,000 per month.13 Nevertheless, the mere presence, however faded, of an arts community gave these neighbourhoods cachet. The traces of a bohemianism appealed to a gentrifying class and in turn, money followed in the form of real estate development. By 2007 much of New York had become prohibitively expensive for artists.

At this juncture, Snow’s gallerists were Melissa Bent and Mirabelle Marden of Rivington Arms, who had also given Colen his first solo exhibition in 2003. Bent met Marden, the daughter of artists Brice and Helen Marden, at Sarah Lawrence College, Yonkers, and in 2002 they opened a gallery on Rivington Street in the Lower East Side, five years before the New Museum relocated to the area. Bent and Marden understood the value of living within the community they represented as a means of cultivating a new art world. As Marden explained in an interview: ‘We love the energy and communal spirit of the neighbourhood, but we also wanted to be near our apartments’.14 The gallerists became poster girls for downtown life – helped in no small part by Marden’s familial association with the earlier scene – while simultaneously maintaining access to the elite world of their wealthy parents. It was within this setting that Colen and Snow operated, and in the context of these overlapping economies this article considers what happens when the nests were made public. How did the idea of the ‘downtown’ as both a real and metaphoric sphere function within these practices? And in what ways does language around artists and the ‘downtown’ become mingled with an aesthetic pursuit?

Nest at Deitch Projects

In 2007 Jeffrey Deitch invited Colen and Snow to install one of their hamster nests at Deitch Projects in SoHo. Founded in 1996, the gallery was known for its ‘audacious programming’, and for championing young artists who were seen to be affiliated with ‘street culture’.15 Deitch was drawn to artists whose practices were ‘indistinguishable’ from their lives,16 a characteristic that was central to much of the historical avant-garde as well to the development of performance art in the 1970s. But Deitch’s interest lay in more extreme examples of this philosophy, which became the focus of the anthology publication – Live Through This: New York 2005, a celebration of the ‘interconnected potentials’ of New York’s downtown scene, a group of fashion designers, musicians and artists, including Colen and Snow.17 These young artists were using their own lives to produce work that purposefully circumvented established ‘economies of exploitation’.18 Although bombarded by demands from commercial forces, these were people who made art for art’s sake.19

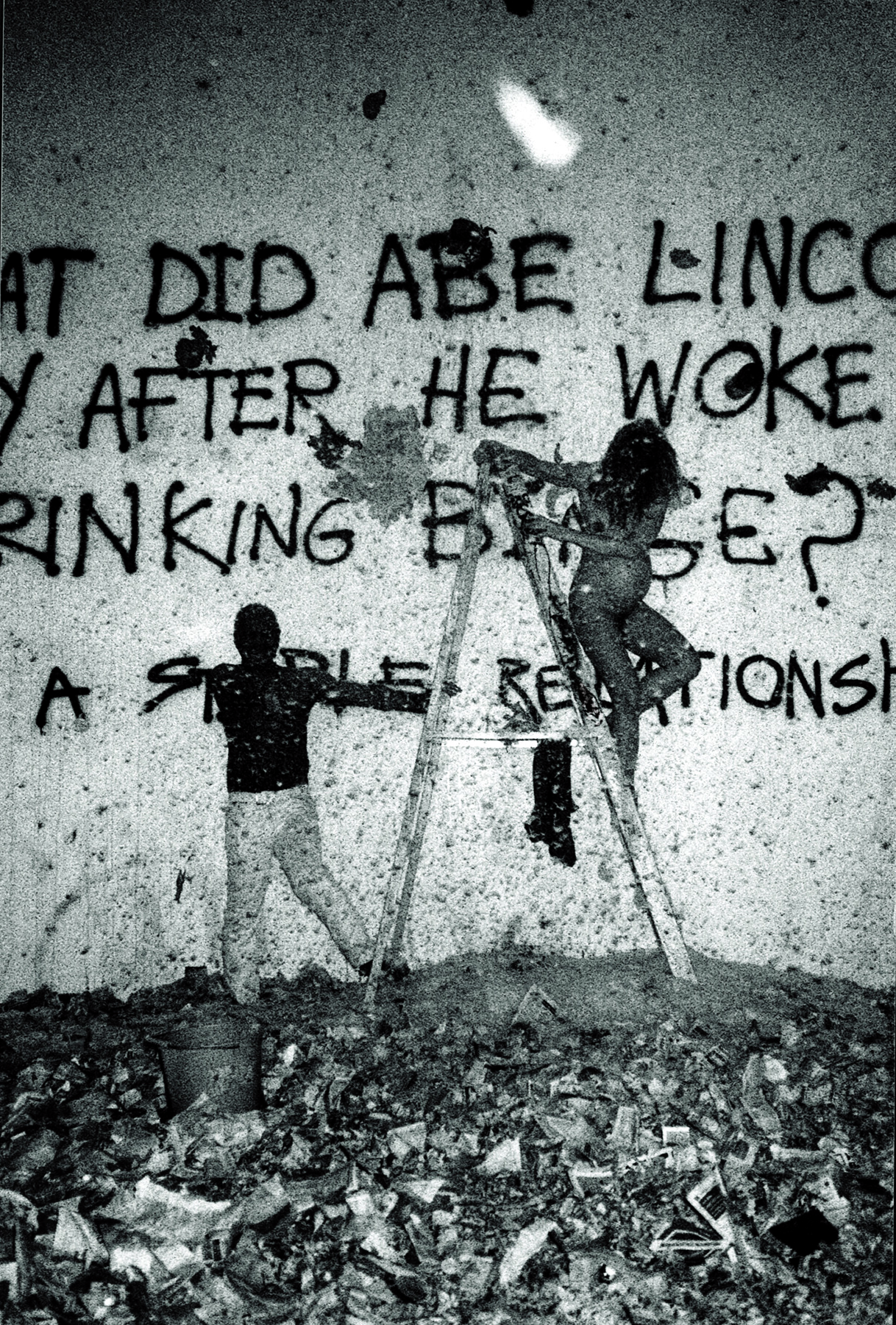

After much deliberation Colen and Snow agreed to create a hamster nest at Deitch Projects on the condition that they could completely take over the space FIG. 4. In preparation for the opening the gallery was filled with a sea of paper, shredded from over two thousand phonebooks FIG. 5. Fifteen other artists were invited to christen the installation and over a five-night period they wrought ‘creative destruction’ on the space FIG. 6.20 Photographs reveal piles of empty cans and bottles; slashed plasterboard; soggy scraps of paper mashed together; and the normally pristine white walls were adorned with inky drawings and crude graffiti – ‘WHAT DID ABE LINCOLN SAY AFTER HE WORK UP FROM A DRINKING BINGE?’; ‘IF YOU CAN’T EAT IT OR FUCK IT THEN TEAR IT UP!’ – to which Snow and Colen added throughout to the exhibition’s run. By charging through the paper piles, visitors also altered the Nest and contributed to its mutating chaos.

The opening of Nest was private and took place on 24th July 2007 FIG. 7. Despite the rubbish and its resulting stench, the critic David Valesco was ‘captivat[ed]’ by the installation, which he likened to ‘a rec room for those who make Vice and i-D magazines vade mecums’.21 He described for Artforum’s Diary column how ‘Stella Schnabel’s leopard-print panties hang like a trophy high above the entrance’.22 Established in 1962, Artforum’s ascent is tied to concept of the critic-scholar. It is a pedigree the magazine takes seriously, and one underscored in the review’s language, which intersperses references to Deleuze and Chuck E. Cheese, describing ‘a salmagundi of feathers, unidentifiable filth, and fluids (mostly piss and liquor, though one hopes for at least a smidgeon of blood and cum)’.22

Diary, which details art-world happenings and gossip, was launched in 2004 by Jack Bankowsky. Charged with bringing more visitors to the magazine’s website, Bankowsky wondered, ‘What would it be like to run a magazine within a magazine, a forum inside Artforum, and one whose purview, rather than art itself, would be “the art world”, the 24-7 social whirl the parent publication’s very identity depends on holding at arm’s length?’24 Since its inception, Diary has relied upon gossip as both an ‘oral artefact’ as well as a mode of production, and it consistently generates the majority of Artforum’s online traffic.25 It is one’s body and biography that hold currency, and even more so when the stories that surface have an underground prestige.

Language and its manipulation are essential to the invention of any public self. Within the art world, as with any celebrity industry, the cultivation of language necessarily shapes understandings of both the work and the artist. Nest served as a form of evidence that was seen to corroborate pre-existing rumours of Colen and Snow’s ‘bad boy’ behaviour. This was perhaps most effectively laid out in Ariel Levy’s contemporaneous profile for New York magazine. Her story remains one of the most substantive pieces of criticism written about these artists and its publication detailed the terms for their celebrity. Levy understood that Snow’s notoriety owed much to the perception of his elusiveness:

You may not be able to find him, but you can hear his name, that zooming syllable – Dash! – punctuating conversations in Chelsea galleries and Lower East Side coke parties and Miami art fairs and the offices of underground newspapers in Copenhagen and Berlin, like a kind of supercool international Morse code.26

Of course, Snow’s involvement with those fairs and shows indicates that he was far from elusive, but such a cultivation became bound up with his artistic identity, projecting as he did a ‘magic flash of insanity, framed and for sale’.22 The New York article foregrounds the importance of gossip to these artists as a means of transforming their lives into cultural capital.

Levy’s article was not well received by Snow or his community, probably because it openly acknowledges the various forces and stakes at play in the success of an artist. It made visible, for instance, Snow’s background and the role of his family in shaping the American art world. Coming from wealth is not an identity easily aligned with the bohemian figure Snow cut in the city. Far from being cynical however, Levy understood the necessary complicity of life as a working artist, a profession dependent upon courtship, patronage and the market.

Another downtown

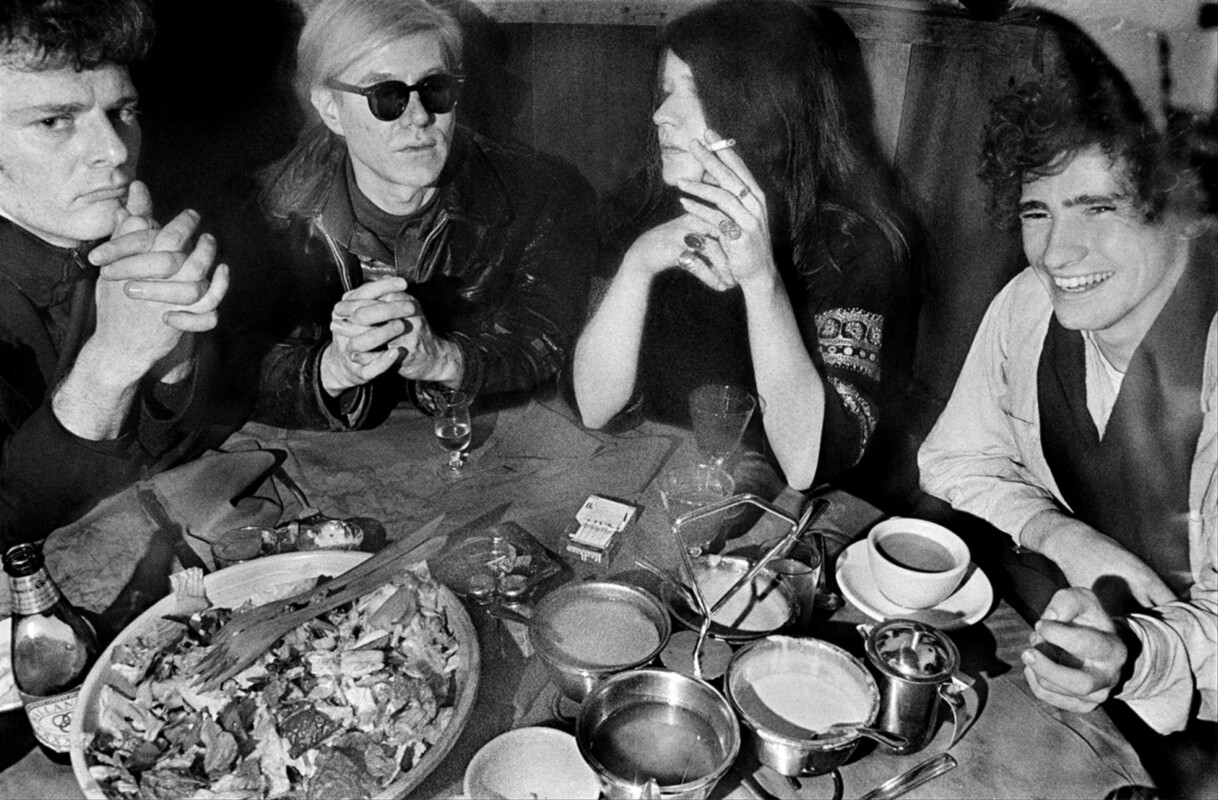

If the 1960s established the idealised language used in relation to New York’s downtown, the 1970s witnessed the exploitation of this rhetoric by Andy Warhol, who developed his ‘brand’ as one contingent upon a specular identity allied with that scene. By embracing countercultural communities at the risk of estranging the more conventional (i.e. uptown, an equally figurative construction establishment), he ‘paved the way for the now ubiquitous recuperation of the underground by the mainstream’, staking his reputation on the idea of an ‘authentic’ downtown artist.28 But Warhol’s downtown was defined by his engagements with the city: a studio on Union Square and nights at Max’s Kansas City took place in neighbourhoods distinct to the Lower East Side or East Village FIG. 8. Instead, the various and distinctive downtowns homogenised to form a single commodifiable entity: a ‘place-identity’ used by both artists and critics to represent a hip, alternative, artistic community; eventually the term was taken up and further reproduced by real estate agencies and within the mass media.29 The downtown scene of the 1980s, argues Christopher Mele, was one characterised by ‘the promotion of self and personality, artistic product, and neighbourhood’.30

By the time Deitch Projects opened in 1996, ‘symbolic representations’ of the downtown had long been ‘transformed from marginal and inferior to central and intriguing’, making a supposedly outsider culture palatable for a mainstream audience.31 Omitting nuance allowed for the marginalised communities of these neighbourhoods to be overlooked and whitewashed to accommodate the moneyed classes. Deitch Projects was able to profit from an ever narrowing and ahistorical conception of downtown, a representation whose very appeal lay in its imprecision. The gallery branded itself as heir to a scene that never existed, improbably located at the intersection of the short-lived East Village arts scene, with its ‘open social network of cheap artist bars’, and SoHo’s storied past.32

Part of what the gallery exhibited and sold was a creative abandon, a risk-filled life supposedly intrinsic to these communities. But as a commercial institution, Deitch Projects could only assume so much of the risk that made these lives seem glamorous. In Nest, for example, the drugs that had been so central to the hotel hamster nests were only obliquely referenced. ‘It’s a miracle that nothing bad happened’, Deitch said of the five-night party leading up to the opening, but in truth the exhibition was meticulously regulated.33 Still, Deitch boasted of the ‘tough street kids’ who arrived and spray painted over the graffiti that Snow and Colen had spent hours ‘subtly orchestrating’;34 he talked about the unexpected arrival of Snow’s ‘tormented’ and ‘estranged’ ex-wife Agathe.22 The success of Nest relied upon such gossip. It confirmed a version of these artists and their alternative lifestyle. Moreover, the inherent variability of Nest – its constantly changing graffiti and mix of makers – encouraged such stories to multiply and morph.

Nest could never be bought or perfectly replicated and in this way Snow and Colen’s strategy mirrored that of Happenings. But although such works share certain formal elements, the social interactions of the Happenings were often more rigidly structured than those of Nest. A more apt comparison can be found in Claes Oldenburg’s immersive installation The Street, whose heaps of wood, wire, and bottles, as well as abstracted figures, signs and automobiles, embodied the violence and dirt of the artist’s Lower East Side neighbourhood. First shown at Judson Gallery, The Street was created against the backdrop of Robert Moses’ plan to remake Lower Manhattan. The work, argues Joshua Shannon, put forth a means for thinking through and reflecting upon the city in light of the proposed project.36 Oldenburg offered up an urban sensation – the boisterous, disarrayed and illegible mess as experienced by a moving body – as an antidote to the rigorous order that Moses wanted to impose on the city.

The visual links between The Street and Nest are clear: both make use of a brown-and-black colour scheme and embrace a sullied materiality. The two also insist upon the fundamental importance of chaos as a strategy.37 Both espouse an interpenetration of context and work: The Street revels in the eternal complexity of urban life as a means of countering Moses’ claims to efficiency, while Nest puts forth a form of defiance as one embedded within a network of bodies. In declaring a hedonistic autonomy, Nest shifts the engagement away from the city’s physical structures and towards the self, moving the myth of the downtown into the body.

Nest is difficult to pin down because it engages anti-elitist strategies while simultaneously relying on and courting a market context. Although the interdependence of consumption and culture has long propelled the art world, Nest was created at a moment when such relationships were becoming all the more explicit. This was true for the artists of the 1960s who ‘circulated transgressive ideas in what would ultimately become acceptable packages’.38 They may have criticised middle-class values but discovered that it was impossible to wholly reject that culture. Nest, however, was never for sale and such ephemerality became its currency: to see the installation at Deitch Projects was to be in the know. At the exhibition’s closing party, Deitch told Artnet TV that ‘this [was] the kind of thing that legend builds around’.39With Nest, Snow and Colen did not radically resist economies of exploitation, but rather gave form to dynamics that have always been at play.