Mining Colombian contemporary art: histories, scales and techniques of gold extraction

by Ana Bilbao • May 2019 • Journal article

Mining for gold has played a fundamental part in Colombia’s religious, social and environmental landscapes since before colonial invasion, and continues to be an important source of income in some rural areas.1 Its history is inseparable from that of the country, from pre-Hispanic cosmovision, through the gold-fuelled economies of colonial and post-independence Colombia, to neo-colonialism in the form of foreign mining companies. The lives and identities of entire communities of indigenous or Afro-Colombian descent revolve around processes of extraction. Gold mining also plays a role in drug trafficking, guerrilla warfare and paramilitarism, as well as in ecology, indigenous and land rights, and art.

This article explores distinct moments in the history of gold extraction in Colombia through the lens of contemporary artists working within their local contexts and three works of art – the film Quiebralomo by Luna Aymara de Los Ríos Agudelo (b.1986) and Mauricio Rivera Henao (b.1980); the installation Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity by the collective Mapa Teatro; and the moving-image work Sin Cielo (Skyless) by Clemencia Echeverri (b.1950) – that articulate distinct visual languages. Together these works attest to the cultural importance of gold, a material that the anthropologist Michael Taussig has argued is a conduit for collective memory and national identity:

Transgressive substances make you want to reach out for a new language of nature, lost to memories of prehistorical time that the present state of emergency recalls, and as fetishes, gold and cocaine play subtle tricks upon human understanding. For it is precisely as mineral or as vegetable matter that they appear to speak for themselves and carry the weight of human history in the guise of natural history.2

While Quiebralomo’s visual language resonates with Colombia’s pre-Hispanic past and with the birth of artisanal techniques, Of Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity gives us a glimpse into the history of small-scale mining that originated during colonialism and Sin Cielo presents the ecological costs of industrial mining in the twenty-first century.

Quiebralomo: pre-Hispanic cosmovision and artisanal mining

In 1534 an indigenous Muisca man from what is today Colombia reportedly told the Spanish conquistadores that one of the ritual ceremonies of his region required the cacique (leader) to cover his body with gold powder. The cacique would then take a boat onto Lake Guatavita and throw himself into the water, along with offerings to the goddess of the lake of gold and emeralds. In its retelling, the story was transformed into the myth of El Dorado, and instead of a man, it became a city, then a kingdom, then an empire that was covered in gold.

An indigenous people and culture that flourished between 600 and 1600, the Muiscas inhabited the highlands of the Colombian Andes, an area roughly co-extensive with today’s departments of Cundinamarca (of which Bogotá is the capital) and Boyacá. In Muisca mythology gold represented the energy contained in the trinity of Chiminigagua, the supreme force and the creator of the world, composed of the moon, the sun and the rainbow. Because of the mineral’s colour, intense brightness and immutability, gold was associated with Sué, the god of the sun. It symbolised the sun’s fertilising sweat and semen and expressed the divine origin of the cacique’s powers.3 Believed to be an intermediary between mortal and other worlds, gold was frequently used in sacrifices, endowing goldsmiths with a special status in Muisca society.4

Silver and copper were thought to be more vulnerable than gold, since they are malleable and their colour changes with time; because their lives have cycles they were associated with the moon. Chía, the goddess of the moon and the companion of Sué, represented fertility, the human embryo and natural cycles. For the Muiscas, time was conceived through cycles such as those of the stars, animal reproduction and menstruation, and was often represented through spiral motifs. In Muisca cosmology, the spiral represented the beginning and the end, the duality of the eternal cycle of Chiminigagua. In Colombian rock art the spiral motif was used to symbolise the sun at solstice.5

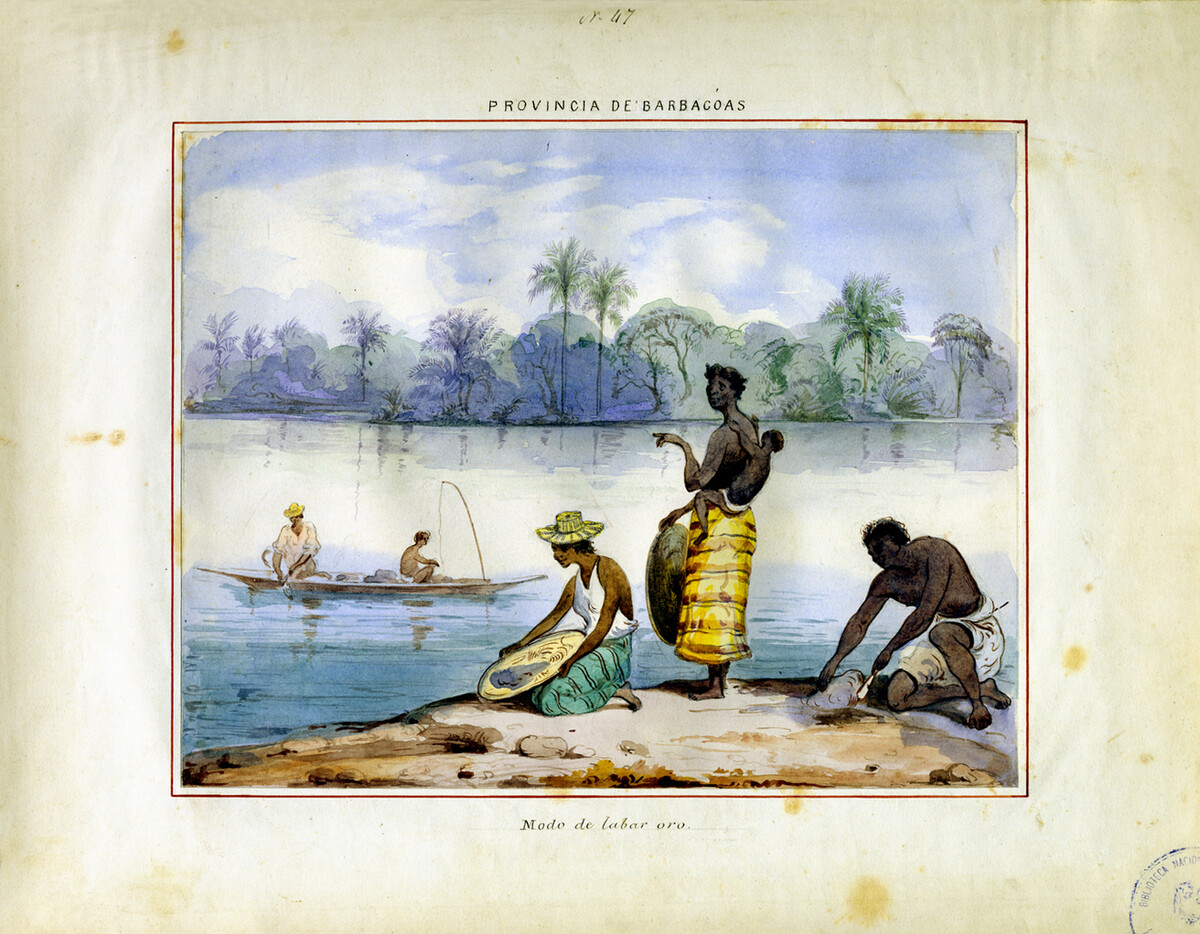

Quiebralomo, originally produced in 2016, was re-edited in 2018 as a part of a large collaborative project by De Los Ríos and Rivera titled Rivera de Los Ríos. De Los Ríos is an artist and anthropologist from Medellín and her work deals with spacio-temporal relations. Rivera is an artist from Pereira whose work focuses on symbolic interactions between humans and nature. The film, which takes its title from the mestizo village of Quiebralomo in Riosucio in the department of Caldas, makes direct reference to the artisanal process of gold extraction called mazamorreo (panning). Practised since pre-Hispanic times, mazamorreo FIG. 1 requires the miner (often female) to dip a wooden board called a batea lightly into a riverbed while making a swirling movement, washing out the gravel and allowing the gold to settle on the surface of the bowl.

Quiebralomo shows a hand performing circular movements with a batea obtained by de Los Ríos from an indigenous man in Riosucio. The movement makes a metal sphere – a Chinese baoding ball – travel in spirals, seemingly producing a noise similar to that of the carts used in industrial mines. The reflective sphere, evocative of treasure and luxury, is not used in mazamorreo. Nonetheless, the hypnotic sound it appears to produce as it circles the batea draws attention to the swirling movement, recalling the gesture that, albeit small, has a significant impact on life in villages around the country. Artisanal mining techniques that do not use chemicals, such as mazamorreo FIG. 2, zambuyidero (a diving technique) and cascajero (gravel mining), are central to many Afro-Colombian communities and shape the organisation of society and the division of labour.6 Although women, men and children are involved, women carry out the majority of the work, while in regions such as Chocó children can start washing the gold from as young as three. At six they can already break rocks and wash them: ‘in indigenous and afro-Colombian communities, the participation of children in gold mining is part of the traditional practice and activities’.7

De los Ríos borrows from archaeology the concept of ‘stratigraphic profile’ to describe the spatial-temporal layers contained in a work of art, including personal and collective memories ready to be unearthed.8 In Quiebralomo both object and movement are extracted from their original contexts and presented to the spectator as art. The batea is therefore removed from its usual muddy and watery landscape and displayed in the centre of a flat, dark expanse. The focal point is enforced by a fixed camera angle, which Rivera describes as an attempt to ‘minimise the staging by reducing distance’ between spectator and object.9 Having removed the batea from the practical context of mazzamoreo, what becomes salient in the work is the movement, the drive to create energy.

A mesmerising audio-visual landscape emerges that is not only an abstraction of contemporary life in an Afro-Colombian mining community but also a glimpse into pre-Hispanic cosmovision. In the same way that the framing of the image in the film emphasises the aesthetic, textural qualities of the batea, interrupting its associations with mazzamoreo, the soundtrack is produced by removing an object from its original context. Although it might at first seem that the sound is produced by the contact between batea and ball, it is in fact a recording of the artists playing a Tibetan singing bowl, an object used in meditation to induce physical harmony. This addition also attributes material powers to the baoding ball that it does not have in its original context, where such balls are used primarily for hand exercises and physiotherapy. Yet embedded in the layers of Rivera’s and de Los Rios’s ‘stratigraphic profile’, the objects are imbued with new associations that are informed by local practices and the historical use of the batea. As the sphere moves across the wood, it evokes the mythical movement of Chiminigagua, the supreme and creative force symbolised by spiral motifs or shapes. The sphere, therefore, is representative of the universe, its movement descriptive of the duality of beginning and end in the eternal cycle of life.10 In Muiscan culture the entire cycle is made possible by the contact between Chía’s embryo and Sué’s fertilising powers. In its ‘stratigraphic profile’, the work represents cultural and ritual practices associated with the process of gold extraction. It both represents community life, and builds bridges between distinct cultures and historical periods.

Of Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity: colonialism and small-scale mining

As the myth of El Dorado illustrates, gold became a primary motivation for Spanish expeditions to the new world. During the sixteenth century, gold extraction was key to economic growth in Nueva Granada and also the basis upon which cities were founded,11 transforming the pattern of indigenous settlement.12 Extraction techniques were learned from the natives, who were forced to work in gold mining together with slaves from Africa.13 Afro-Colombian communities still use techniques learned from indigenous populations during colonialism, including mazamorreo.14 These artisanal methods, however, are not the most effective techniques, since small pieces of gold can be lost and the gold cannot be completely separated from other metals, thereby affecting its purity. Small-scale mining emerged during colonialism as it became clear that water was crucial for improving processes of gold extraction. Gutters and wells were constructed in order to optimise the gathering and washing of the gravel and sinkholes were dug to extract veins of gold, which, although a complicated procedure, turned out to be one of the most productive techniques. Once the material was extracted, it was ground with tools made of iron and steel, and then separated with the batea. Tools such as the barra (rod mill) and almocafre (weeding hoe) were imported from Europe and used to obtain gravel and carry it to the gutters.15 In the eighteenth century, Charles III of Spain sent German mining engineers to Colombia to explore new extractive techniques, together with the chemist and mineralogist Juan José D’Elhúyar and his brother-in-law, the metallurgist engineer Ángel Díaz Castellanos, who were charged with modernising the mines and making them more profitable.16 These missions resulted in an increase in mining.17

Of Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity is an ‘ethno-fiction’ installed at the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid (October 2018–April 2019), by Mapa Teatro, a collective based in Bogotá that was formed in Paris by siblings Heidi and Rolf Eugenio Abderhalden Cortés in 1984. Their practice explores the intersections between visual arts and theatre. They experiment with media such as theatre, video, installation, opera, radio, urban interventions and lecture-performances, and their work draws on myth, history and archival documentation to aid them in constructing fictions. In the sixteenth century the building that now houses the museum was Madrid’s General Hospital, founded by Philip II. An eighteenth-century renovation of the hospital by the royal family was largely financed by gold from Latin America. The basement of the building was dedicated to assisting those who were considered to be ‘lunatics or lacking sanity’; this formed the principal setting for the installation of the same name.

As part of the installation Mapa Teatro traced the steps of the European engineers sent to Nueva Granada by Charles III. This research led the collective to the mines of Marmato, which have remained in use since before colonisation. On the basis of these materials Mapa Teatro created a fiction that narrates how Díaz Castellanos suffered symptoms of so-called ‘auriferis delirium’, supposedly a common illness at the time FIG. 3.

Unlike artisanal mining, which the government defines as processes that only include panning, small-scale mining techniques make use of suction and spoon dredges, water pumps, sluice boxes and hydraulic excavators. Most notably, however, this type of mining uses mercury, which easily amalgamates with gold and therefore allows to recover small pieces that would otherwise be lost.18 Mercury and cyanide (also used for extracting gold) are toxic and their release into the environment contributes to deforestation and causes water and food pollution. When ingested, these chemicals can lead to memory loss and damage the nervous system and internal organs. Although it is known that Díaz Castellanos died in Quiebralomo, Mapa Teatro’s fictitious account relates how he had to return to Spain due to similar health concerns to be treated in the basement of the General Hospital.19 The installation thus built a subtle anachronic bridge between the development of new extractive processes during colonialism and their contemporary and now well-documented impact on local communities.

Since the early 2000s the Colombian government has been quick to release permits to large-scale foreign mining corporations, but slower to respond to requests by small-scale miners, forcing many to work illegally.20 As a result, most miners have no explicit rights, live under precarious conditions and are vulnerable to encounters with armed groups. In regions that are rich in mining areas, such as Chocó, Bolívar and Antioquia, left-wing guerrilla groups, including FARC and ELN, have a strong presence, as do the Bacrim, dissident members of extreme right-wing paramilitary groups that were disarmed and demobilised between 2003 and 2006.21 With the decline in cocaine production in the late 1990s, both guerrillas and paramilitaries turned their attention to gold. As shown in the documentary Por todo el oro de Colombia made in 2012 by Roméo Langlois and Pascale Mariani, small-scale miners often worked in the mountains under FARC rule.22 They had to pay for land and extraction rights in order to sustain an activity that would allow their community to survive, thus involuntarily funding the armed conflict that has continued since the 1960s.

Small-scale mining has led to tensions between the economic development of the community, traditional practices and the conservation of the environment. As of 2013, mercury pollution rates in Colombia were the highest in the world,23 while the migrations of miners seeking work has put pressure on resident communities.4 For instance, a conflict arose in 2012 between miners and the indigenous Nasas from Cauca, who protest vehemently against the damage that mining practices cause to their land. For them, the ‘sacred mountains are worth more than all the gold in Colombia’.25

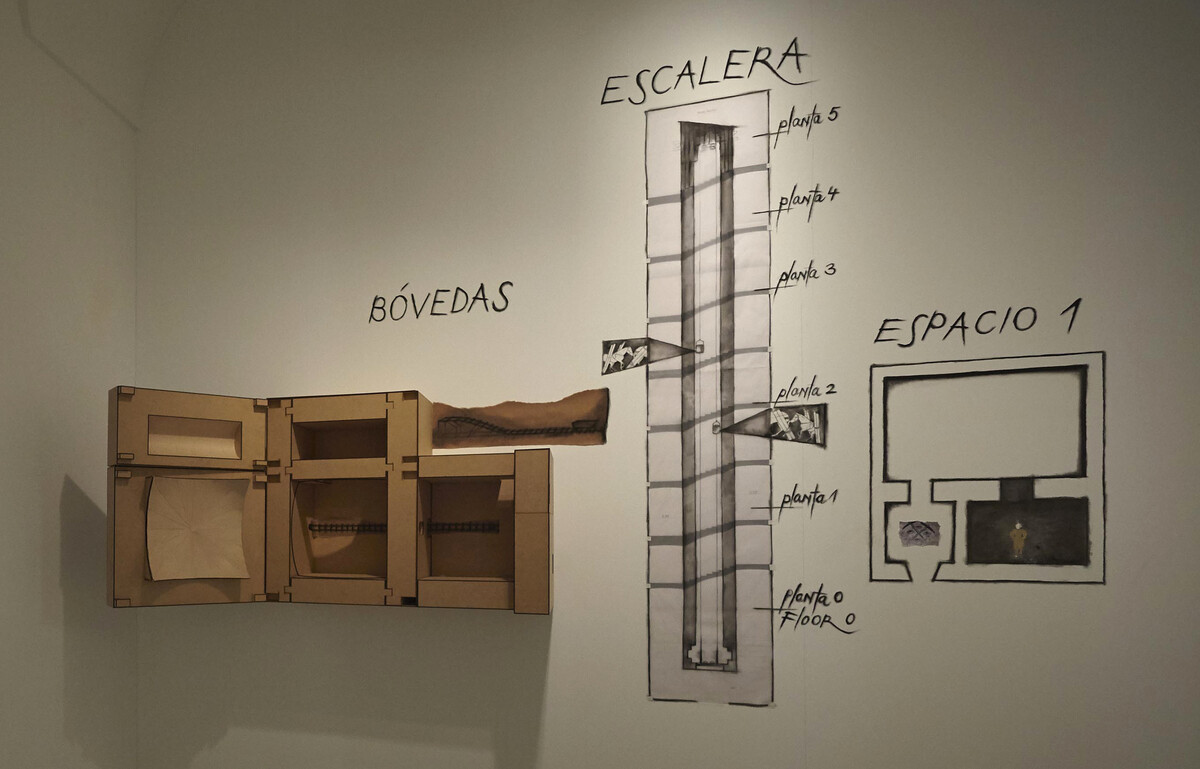

Of Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity was installed in three spaces in the museum: Espacio 1; the stairwell; and the Sala de Bóvedas (basement hall) FIG. 4. Espacio 1 exhibits research, films of mines FIG. 5, colonial maps with drawings of indigenous and African men, hospital documents from the archives, ordinances, letters from Díaz Castellanos and journal articles. The fictional narrative was presented in this space: the text on the wall combined archival materials with fantasy texts describing the symptoms and behaviours that Díaz supposedly experienced while ill.

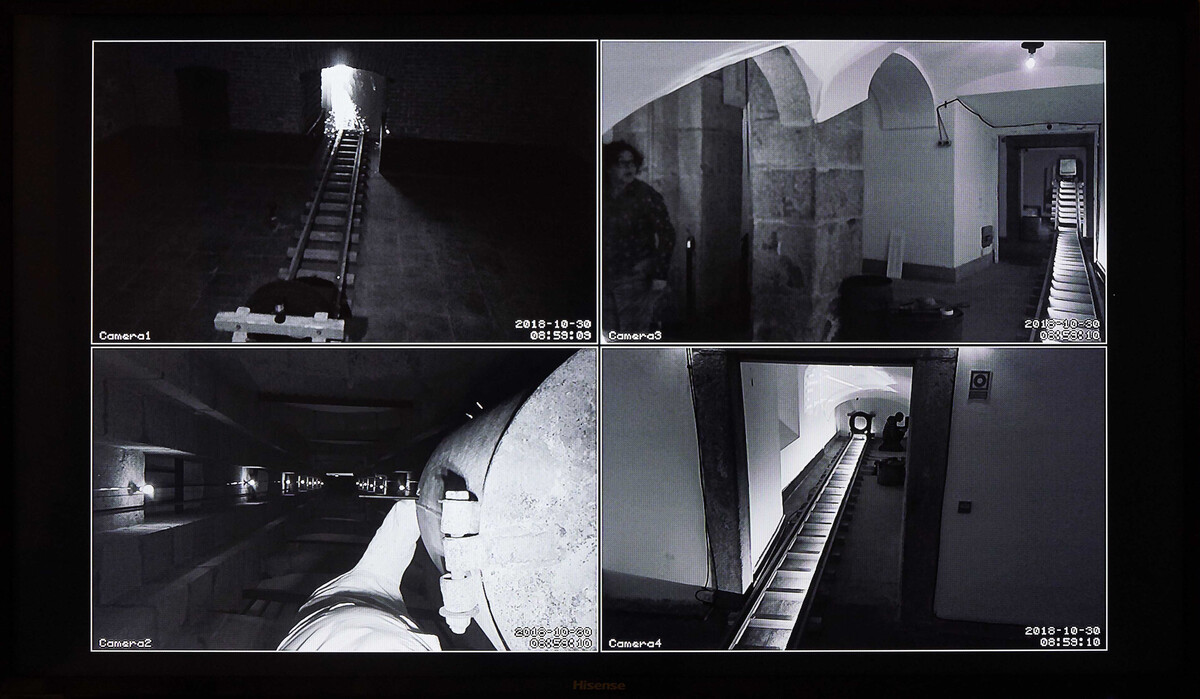

In the same room a screen displayed a closed-circuit television system that allowed visitors to see into the other two spaces FIG. 6, serving as a thread that connected works dispersed in different areas of the museum building and offering a window onto how visitors related to the space. On the staircase an audio-visual installation traverses five floors, including projected images of the pack mules used to access the mines and to assist workers. Running down the stairs in front of the projection was a wagon track like those found in mines to transport materials. Miniature wagons constantly travelled to the underground space FIG. 7 where patients were treated. The basement contained a second audio-visual installation, in which the space of a traditional mine was recreated using materials brought from Colombia FIG. 8. Footage recorded in the Marmato mines in Colombia was projected onto the wall.

Of Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity traces and reconstructs aspects of the history of small-scale mining and its origins in colonialism. It illustrates the precarious situation of the miners of Marmato, who continue to defend their labour against the monopolising gestures of multinational companies. Through the footage one can appreciate the resilience of the local miners who in the second half of the twentieth century attempted to resist the pressures coming from different factions of the armed conflict. The catalogue of the exhibition raises the issue of delirium. The myth of El Dorado was a delirium that had long lasting consequences, such as racialisation and unhinged capitalist global exploitation.26 Images shown in the projections often show working hands, touching and moulding the material. One can only wonder about the health consequences of such intense contact between substance and skin; it is as if the body of the miner is perceived as disposable, as if the hands’ only function was to serve as means to extract material resources. Departing from the fictional character present in most of the work, these images momentarily create links between racialisation and capitalist exploitation.

By blending fact and fiction, Mapa Teatro activates a distinct kind of spectatorship at the intersection between visual arts and theatre. This position blurs the museum’s claim to truth or knowledge with the experience of theatre, which traditionally entails a total or partial suspension of reality. In this sense, the work reverberates with the myth of El Dorado, of a fantasy goldmine that engendered colonisation and exploitation. The spectator is made to participate physically in this ethno-fiction in two ways: first, they are physically immersed in the effects of gold extraction by means of being inside the hospital built with profits from that gold. Secondly, the dispersal of the installation across the museum means that visitors must travel across spaces and levels, which recreates the miners’ journey and requires ‘physical exhaustion and real imaginative engagement’.27 Exhaustion is certainly a common thread between the miners’ experience during colonial times and the miners’ experience today, and also contributes to the inverting traditional roles of spectatorship in visual arts and theatre, where it is the actresses and actors who are expected to exert themselves for a static, usually seated, audience. While nodding towards institutional critique, Of Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity configures a distinct mode of experiencing art that activates different temporalities and offers a kaleidoscopic viewpoint of the historical, economic, social and physical effects of gold extraction.

Sin Cielo: contemporary large-scale transnational mining

Gold production reached its peak in Colombia in 1940. Between the 1950s and 1980s official statistics record a dramatic decrease. However, studies indicate that these statistics did not account for clandestine exports and in fact production remained stable.28 Production rose in the 1980s with the exploration of new regions, an increase in the price of gold and the setting of national prices to equal international prices.29 In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the government of President Andrés Pastrana Arango instituted a neoliberal model for extraction with the aim of attracting foreign investment. This was extended during the administrations of Alvaro Uribe (2002–10) and Juan Manuel Santos (2010–18). The arrival of multinational companies has caused tensions between the government and indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities engaged in small-scale and artisanal mining.30 For example, local miners refer to the Canadian company Gran Colombia Gold as the ‘new conquistadores’.31

Techniques for large-scale extraction include alluvial and open-pit mining as well as underground mining, used for deposits deeper than one hundred metres. Open-pit mining involves removing topsoil with significant amounts of explosives, encouraging erosion and altering the composition of the soil, causing sterility. As in small-scale mining, water, mercury and cyanide are used, but in larger amounts. Large-scale mining often requires the diversion of rivers, which has significant environmental impact. Furthermore, air, water and noise pollution damage local ecosystems.32

A report by the U.S. Office on Colombia in 2013 indicates that neither the government nor commercial bodies have been able to mitigate environmental risks or human rights violations, meaning that large-scale mining poses an ‘imminent threat’.33 Although much of the land subject to industrial mining is protected by law following consultation processes with Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities regarding ancestral lands, protests against mining on this basis have seen little success. Indeed, transnational companies have in some cases taken legal action against such communities for allegedly ‘obstructing their right to do business’.34 In other cases, community leaders have been subject to deadly attacks.35 The lands of indigenous, Afro, Raizal, Roma and Palenquero communities have been promised for large-scale mining, often resulting in forced displacement.36 The report concludes that sustainable peace in the country would require further discussions on mineral rights in relation to economic growth and armed group violence, alongside ‘issues of rural and human development’.37

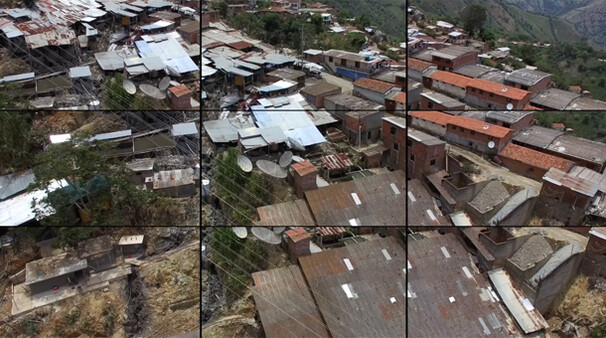

Sin Cielo (2017) is a video installation comprised of nine HD monitors by Echeverri (b.1950). The artist lives and works in Bogotá. After exploring painting and sculpture as mediums in the 1990s, she started working with installation, video, photography and sound. In recent years her work has been focused on sensorial and corporeal approximations to space, often related to her interest in territorialisation and de-territorialisation in the context of the recent socio-political history of her country.38 The monitors show fragmented scenes of gold extraction and its effects on the landscape around Marmato. However, during the editing process, the work was conceived simultaneously across the nine monitors. In this manner, Sin Cielo was thought of as a place able to account for the fragmentation of space, rhythms and temporalities of the work.39 Images decompose and recompose, each time offering us a different view.

One scene shows traces of mercury and cyanide in the form of a toxic mud that trickles down fractures in the mountains. The landscape is investigated slowly and thoroughly by drone,40 almost in a forensic manner. It is precisely this investigative process – mediated by cameras and drones – that confronts the spectator with the causes of the hurt landscape presenting evidence difficult to ignore. The Canadian artist Charles Stankievech has defined forensic art as ‘art that either uses forensic strategies or engages in a commentary on forensic processes’, arguing that such art often serves as ‘counter forensics – a strategy to contest the status quo or state power’.41 Sin Cielo is, albeit not deliberately, a work that adheres to this aesthetics of evidence problematised by Stankievech.

As legal cases contesting industrial mining in Colombia resulted in little success – and provoked legal action in return – the question is whether works that make use of an aesthetics of evidence are able to serve as effective counter forensics, and, if so, whether this represents a conflict of interest with their aesthetic value. In this regard, Sin Cielo offers a space for concomitance by inverting the roles of spectator and landscape, challenging our conceptions of a passive landscape that merely witnesses conflict and revealing the intrinsic connections between social and environmental violence.42 Echeverri does not include any voices of the people affected by the arrival of transnational companies.43 Instead, the image of the landscape is allowed to disclose its own audio-visual narrative, bringing it to the fore as a suffering agent and not only as the stage for violence. This, however, does not detract from the evidentiary value of the work. On the contrary, the medium itself – video – acts here as a mediator between us and the realities of Caldas. Sin Cielo allows the viewer to see corners of the earth inaccessible to our sight, inviting close attention to the skin of the earth and the stories that it contains and expresses of neo-colonisation, violence, abuse and displacement caused by gold extraction. Sin Cielo is an uncomfortable work. It does not demand the spectator to react or participate, but instead inverts the roles, portraying the landscape as an active suffering agent and the viewer as a mere impotent witness.

The three projects discussed in this article are among an increasing number of works by artists and collectives that are turning their attention towards the effects of extractivism in Colombia. As well as those artists working specifically on gold extraction including Fredy Alzate, Miguel Ángel Rojas and Mario Opazo, there are others examining the commodity-based use of natural resources in the country, notably Carolina Caycedo, whose project Be Damned (2012–) examines the impact of dams in Latin American countries.44 Quiebralomo, Lunatics or Those Lacking Sanity and Sin Cielo also link to the interdisciplinary field of enquiry that draws intersections between extractivism and contemporary visual art from Latin America.45 However, each work also relates to other lines of enquiry including institutional critique and aesthetics of evidence that are shared by contemporary artists elsewhere. The three works foreground gold as a transgressive substance, both symbolically and trans-historically. Gold serves as an intermediary between peoples and cultures, cutting across distinct forms of cosmovision. The exhausting physical experience of a miner’s journey evokes the process of extraction, blurring the lines between fact and fiction. Finally, gold is presented as the substance liable for harming the earth; as Taussig asserts, it ‘appears to speak for itself, carrying the weight of human history in the guise of natural history’. As these works illustrate, transgressive substances also make us want to reach out for a new language of art, for new forms and new modes of spectatorship, carrying the weight of human history in the guise of art history.

Acknowledgments

I would like thank Acción Cultural Española and lugar a dudas in Cali, who made this research possible. I am also grateful to Mauricio Rivera Henao, Luna Aymara de los Ríos Agudelo, Heidi and Rolf Eugenio Abderhalden Cortés, and Clemencia Echeverri for their generous contribution to this research.