Living extinction: Robert Smithson’s dinosaurs

by Suzaan Boettger • November 2021

The dinosaurs made a tremendous impression on me. I think this initial impact is still in my psyche. – Robert Smithson

Imagine a sound like a hollow metal tube repetitiously rapping and echoing in a vault, low and eerie.1 It is heard approximately five minutes into Robert Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty, enhancing the strangely florid atmosphere pervading the screen, where appear indistinct forms of towering dark creatures FIG. 1. We are inside the American Museum of Natural History in New York, wondering what looming dinosaur skeletons rendered black by the camera’s red filter have to do with Smithson’s earthwork of the same name on the north-eastern shore of Great Salt Lake, Utah.

Throughout his life, writings and art, Smithson (1938–73) displayed a connection to dinosaurs that extended far beyond a common childhood fascination with the ‘brutes’ that the science fiction novelist Eric Temple Bell, whom he often quoted, likened to ‘no prehistoric monster known to science’.2 In fact, the creatures that Smithson filmed have since been identified as Gorgosaurus.3 More significantly, the importance of the beasts to Smithson has so far gone unrecognised in the art world. Both the idea of ‘prehistory’ and the unknown quality of the ‘prehistoric monsters’, as emphasised by Bell, drew Smithson’s attention. Evidently, they held an iconic power for him, such that, even when Smithson was thirty-two years old, dinosaurs haunted his autobiographical film Spiral Jetty. Speaking to Paul Cummings in a 1972 interview for the Archives of American Art Oral History programme, Smithson acknowledged that ‘the prehistoric motif runs throughout’ his œuvre.4 And for him prehistory was the domain of dinosaurs.

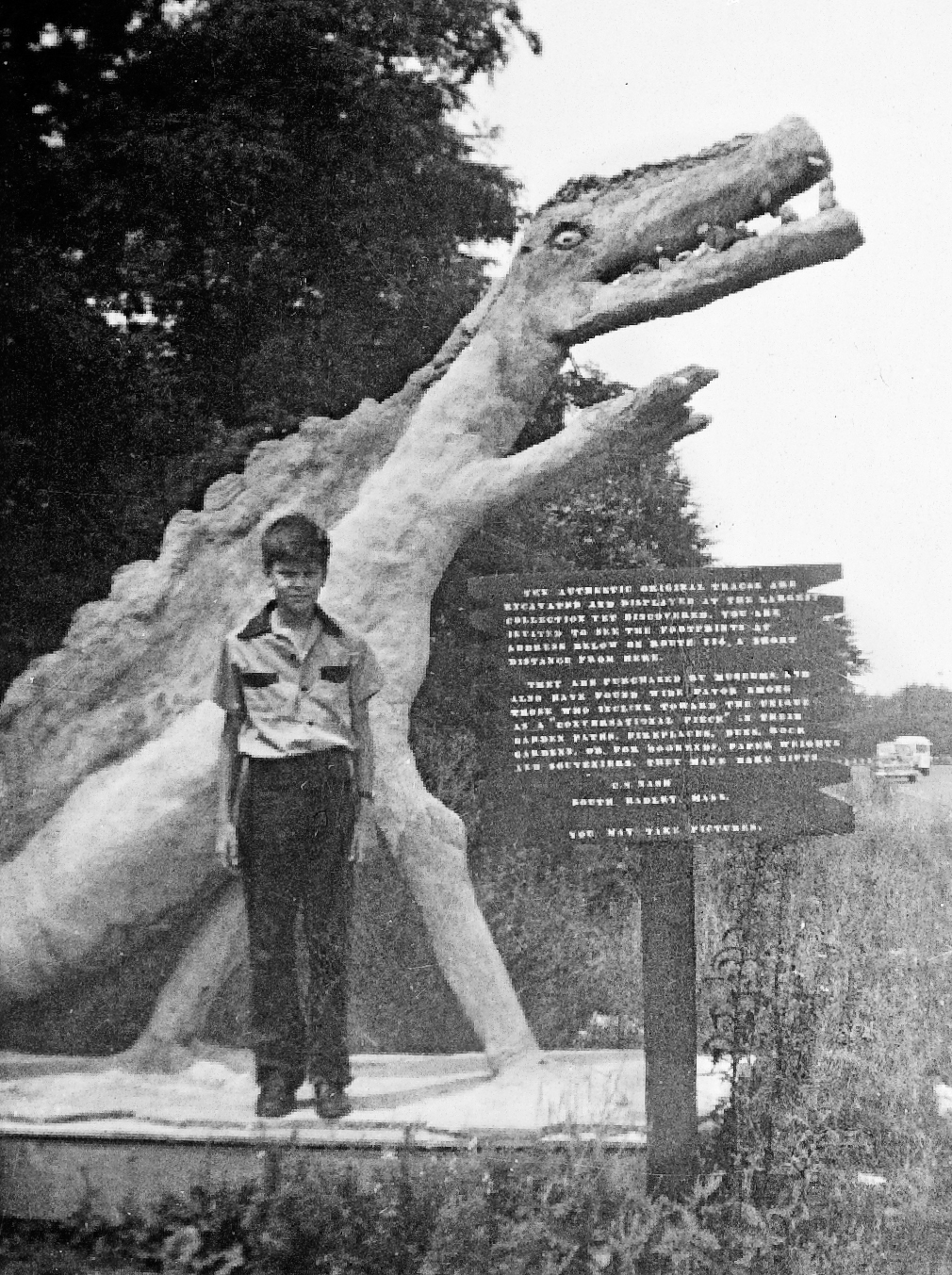

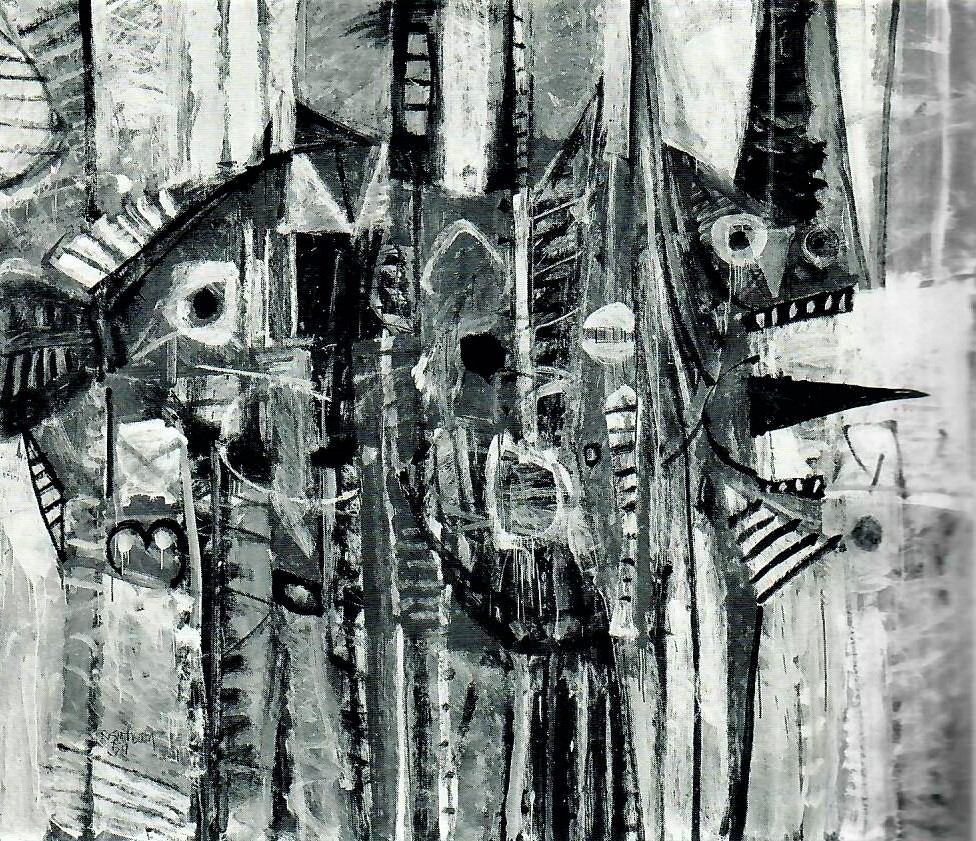

‘We used to go to the Museum of Natural History all the time’, Smithson recounted, detailing visits with his father from across the Hudson River in suburban New Jersey.5 Aged seven, he constructed paper dinosaurs and drew a large mural of one for the hallway of his elementary school. Around the age of ten, he and his parents visited the site of dinosaur tracks near South Hadley, Massachusetts FIG. 2; at fourteen, he planned a family trip to a dinosaur park in Rapid City, South Dakota. In his solo show at The Artists’ Gallery in Manhattan in 1959, when he was twenty-one, he displayed paintings titled Blue Dinosaur and White Dinosaur. These and the other fourteen works on the show’s checklist have since disappeared, presumably discarded by the artist, as he ambivalently described: ‘I destroyed a lot of them. Those are really like talented early work that I grew dissatisfied with’.6 A black-and-white photograph of Blue Dinosaur FIG. 3 shows that the creature was barely perceptible, embedded in – or penetrated by – vertical painterly stripes. Nonetheless, one can discern a rotund form with a series of triangular back plates along its spine, a thick tail and, most prominently, widened eyes and an open jaw with bared teeth and a long, protruding tongue. Years later, Smithson accurately defined the origin of the word ‘dinosaur’ as ‘terrible lizard’; as coined in 1842 by the English zoologist Richard Owen, from the Greek words deinos (terrible) and saurus (lizard).7

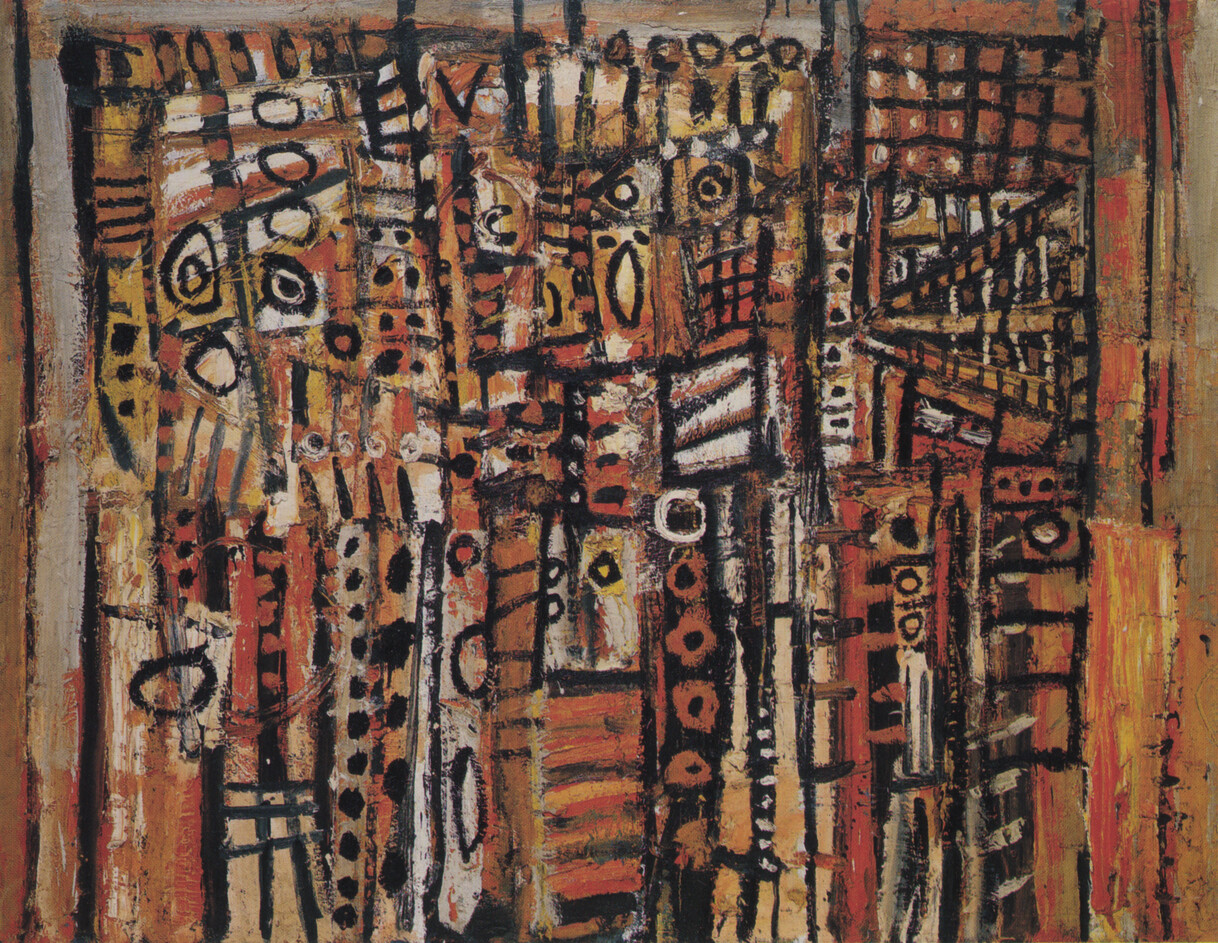

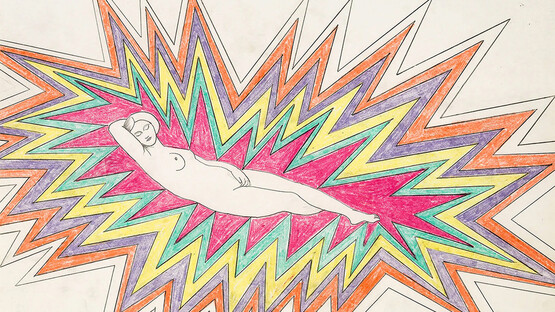

As a painter who made drawings, Smithson depicted that devouring demon several times. In the aforementioned 1959 exhibition, the big eyes, gaping mouth and broad, forked tongue also appeared in Flesh Eater and in the now lost triptych Walls of Dis FIG. 4. Dis is the name of the capital city in the lowest three circles of hell in Dante’s Inferno, and it appears that Smithson was so engaged with the subject that he painted it twice. In his second work titled Walls of Dis FIG. 5, also made in 1959, the triangular open jaws and horizontal tongue have been subsumed into an abstraction of thick black lines, grids, circles and black dots on a rust-orange field, suggesting a crowd of eyes behind the wall’s grid.

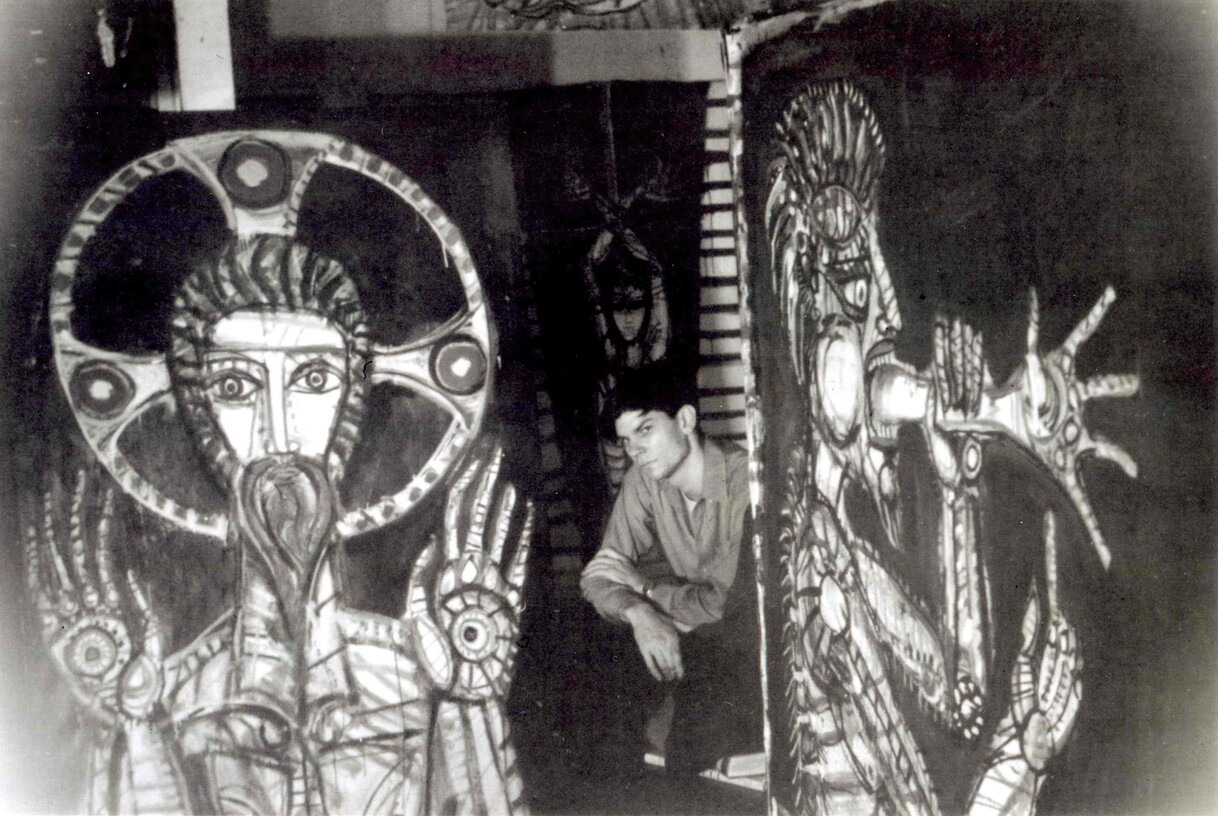

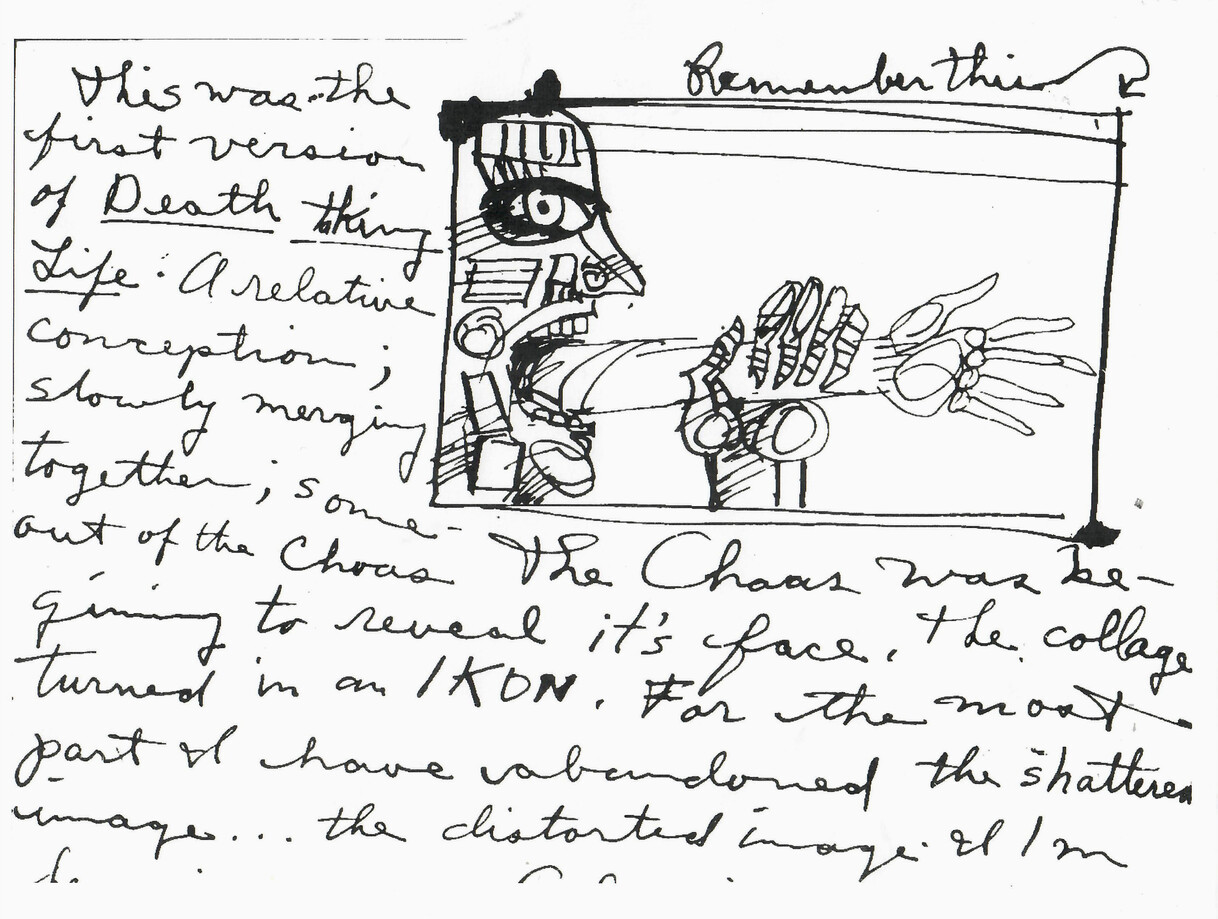

In around 1960 Smithson was photographed in his studio next to a large painting that depicts a creature with a teeth-bared, open jaw profile that is similar to those in Blue Dinosaur and Flesh Eater, with the addition of a victim’s arm in the mouth FIG. 6. Here the carnivore appears human, evoking a famous precedent of a male chomping on another’s arm, Francisco Goya’s Saturn devouring one of his children (1820–23; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid). Smithson’s schematic head reduces and flattens Goya’s broadly brushed volumetric nude. We know that the painting was titled Death Taking Life because Smithson sketched it in a gouache in a letter to his gallerist in Rome (Galeria George Lester) FIG. 7. It had been purchased by Raymond Saroff, who saw Smithson’s exhibition at The Artists’ Gallery and subsequently visited his studio in Chelsea to view more of his work. Saroff recalled that 1960 visit: ‘I liked what he was doing – the artistic brain behind them. The images’ grotesqueness appealed to me’.8 Death Taking Life was acquired in 2006 by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; although the present author has informed the curatorial department of Smithson’s letter, it continues to be catalogued as Untitled FIG. 8. The Whitney is one of the few museums in the world to own a Smithson painting, most of which, like this example, are on paper.

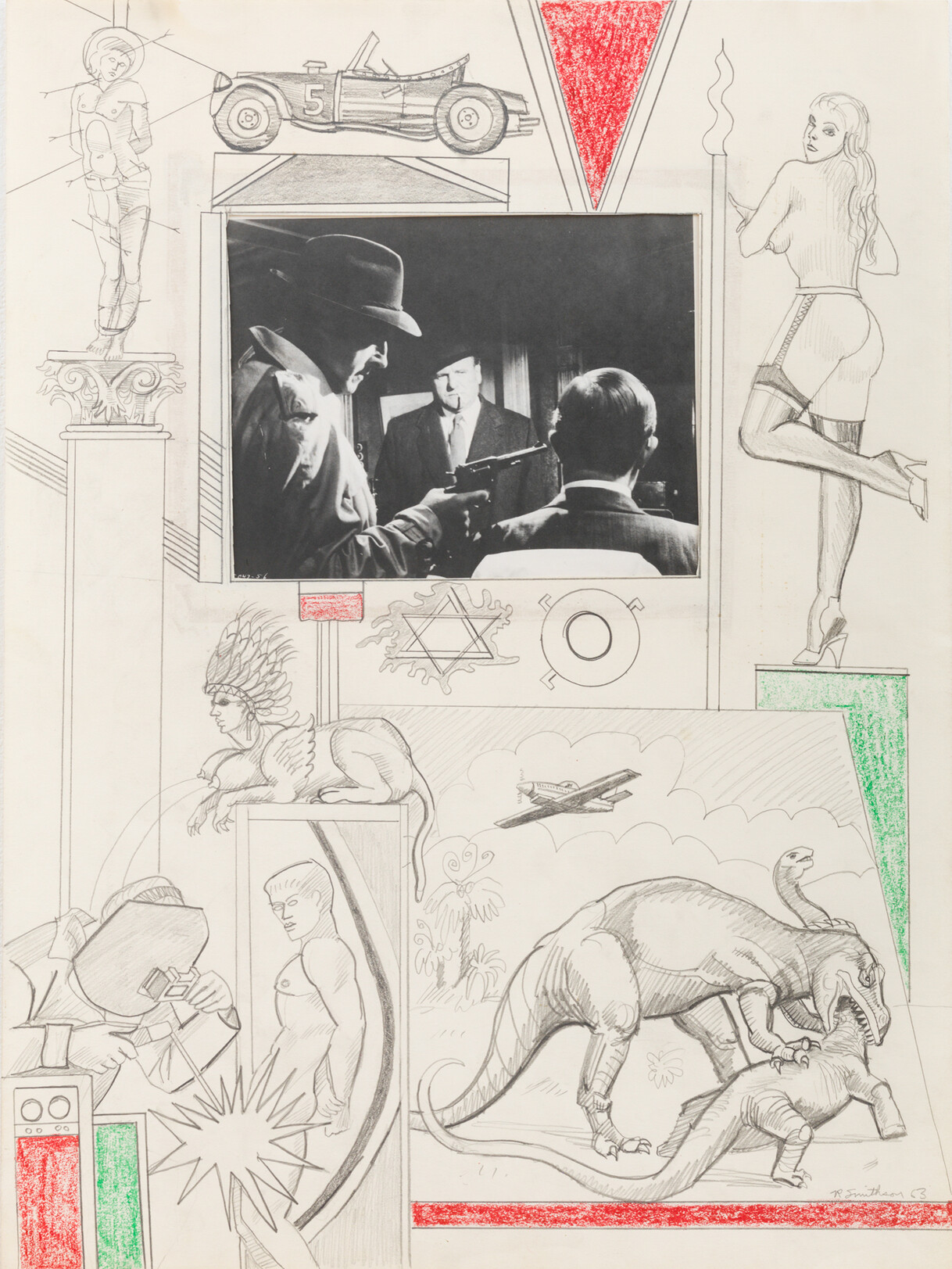

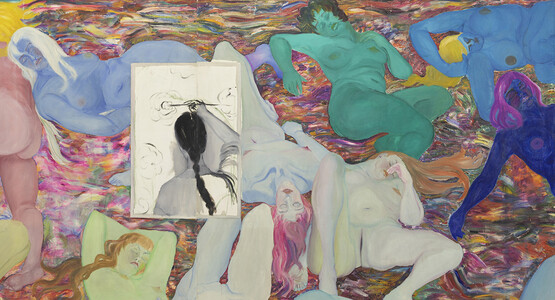

Around late 1964 Smithson stopped painting and began a professional transition; in 1965 he exhibited as what could be called a ‘proto-sculptor’, that is, showing constructions of planar plastics hung on the wall. From 1960 to 1964 he produced a large number of drawings: fanciful angels and fantastic hybrid creatures; scrawled repeated words and languorous male nudes. These demonstrate a radical change in the artist’s style – to gambolling graphite figures rendered in crisply outlined academic idealisation and shading with soft coloured pencil. In these drawings, nudes are often arranged around a central rectangular collage, its elements cut from decorative shelf paper or from an illustrated book, periodical or catalogue. Years later, Smithson cleverly if grandiosely compared the central, flattened components of these compositions to a ‘cartouche’ – an architectural ornament simulating an unrolled scroll or tablet, often a stone panel with or without incised text and often surrounded by Baroque flourishes.9 Although Smithson signed and dated his ‘cartouche’ drawings, he did not title them, and there is no evidence that he either sought to exhibit them or that they were shown during his lifetime. This suggests their function as private expressions or personal visual pleasures. His assemblage of figures around the core image do not align into a narrative arc or cohesive meaning.

In one of these drawings, from 1963, the dinosaurs, rendered in a way characteristic of Smithson’s works in the period, have mutated into naturalistic realism FIG. 9. In the lower right-hand corner two dinosaurs brawl, a larger one lunging over the other; a plane flies overhead, suggesting that these are not prehistoric creatures but are living in modern times (it is worth noting that this drawing predates Michael Crichton’s novel and Jurassic Park films by decades). At the top right, a vintage-style female ‘pin-up’ poses on a plinth, nude except for a 1940s-era garter belt, stockings and heels. A hot rod with racing stripes and a number five – perhaps a reference to I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold by Charles Demuth (1928; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and, by extension, a nod to Demuth’s openly gay identity – directs the eye to St Sebastian in the top left corner, who also stands on a pedestal, haloed and nude except for a loin cloth, punctured by many arrows. He represents another sort of allure. Smithson, who was widely read and in his drawings displayed an appreciation for homosexual eroticism, depicted a saint to whom gay writers and artists were particularly drawn.10 Particularly in the post-war period of homophobia, St Sebastian’s mixture of statuesque physique and evocation of the rapture of penetration offered an exemplar of fortitude for those whose inclinations put them at risk of being personally and professionally martyred. Gay – or in Smithson’s case, sexually fluid men – could identify with the saint’s mixture of masculine beauty and torture.

In the centre of the work, Smithson has re-gendered a sphinx. In classical mythology and its nineteenth-century adoptions, the sphinx was depicted with the head and breasts of a woman and the body of a lion. Here, Smithson has subverted the traditional gendered characteristics: the facial profile of his sphinx is decidedly masculine and wears a native American chief’s headdress and sunglasses with round frames similar to those worn by Piet Mondrian and Le Corbusier and later adopted by John Lennon and I.M. Pei – a sort of insignia of creative intellectuality. The sphinx’s tumescent breasts still signal a female identity, but they squirt liquid onto the men below so propulsively as to evoke not lactation but male urination. The hooded welder below ignores the stream; he is focused intently on the crotch of a well-built man, from which radiates signs of explosive energy – or excitement.

All of these images encircle a collaged black-and-white photograph, unidentified by Smithson, of a man pointing a gun at the head of a seated man seen from the back, who is being interrogated by a third male. It is a still from the 1961 British thriller film The Secret Partner, in which the protagonist is blackmailed by a villain who himself is being threatened by a mysterious man. In this composition’s panoply of sex and aggression – made in the same year that Smithson and his childhood neighbour and classmate Nancy Holt married in an uptown Manhattan Catholic church – any one of the figures could be Smithson’s ‘secret partner’. It provides a provocative context to his choice to depict, of all arenas in Dante’s Inferno, Dis, the penal confinement assigned to the violent and bestial, fraudulent, hypocrites and betrayers.

In 1966 Smithson co-authored an article on the Museum of Natural History’s Hayden Planetarium with Mel Bochner;11 in it they included a mural of a dinosaur watching an exploding meteor painted by staff member Thomas W. Vater, who in 1956 had illustrated the book All About Dinosaurs. Two years later, aged thirty, Smithson published an essay ‘A museum of language in the vicinity of art’ with a postcard of a painting by Charles R. Knight of a marsh with a brontosaurus.12 At this time or perhaps shortly thereafter, he acquired a copy of The Day of the Dinosaur (1968), an illustrated science book.13 In his Spiral Jetty film he pictured the book at the bottom of a stack topped with a 1965 edition of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). Two years later, Smithson affirmed that at this time dinosaurs were much on his mind. He recalled ‘titles like White Dinosaur, which I think carries through right now, a similar kind of preoccupation’.14 This implies that his connection to dinosaurs transcended his stylistic transitions – across painting, sculpture, earthwork and film-making. He made their enduring presence emphatic by declaring ‘the dinosaurs made a tremendous impression on me. I think this initial impact is still in my psyche’.15 His locution suggests the impression was like a deep crater.

After giving a lecture about Spiral Jetty, Smithson told the architect, artist and art critic Gianni Pettena that he liked ‘landscapes that suggest prehistory’.16 In cultural history, the early natural world is conventionally idealised as an Edenic purity – what in a private essay written a decade earlier Smithson had lamented as ‘a terrible yearning for Innocence stares back over Original Sin into some impossible paradise’.17 Later his embrace of the entropic became central to his self-representation: ‘I think that’s part of the attraction of people going to visit obsolete civilisations. They get a gratification from the collapse of these things’.18 These statements frame his presentation of the site of the Spiral Jetty as a prehistoric environment, which he described as ‘countless bits of wreckage’ caught in ‘sediments of salt flats border[ing] the lake’. He further commented that ‘The mere sight of the trapped fragments of junk and waste transported one into a world of modern prehistory’.19 In the film he manifested this idea by interspersing a grunting bulldozer piling earth to form the jetty with a view of a painting of stegosaurus dinosaurs by George Geselschap for the American Museum of Natural History FIG. 10. In the museum, the wall panel was located behind a display case of fossils and had been on view from 1935 to 1960. FIG. 11 Since childhood Smithson had collected and maintained an interest in fossils. Therefore, for his 1970 film he must have photographed an illustration of the painting in a Readers Digest book, Our Amazing World of Nature, Its Marvels and Mysteries (1969). Its five-second glimpse then appears as if a transient flashback.

At another point in the film, as the camera pans over the radiantly carmine view of the dinosaur skeletons, Smithson intones:

Nothing has ever changed since I have been here. But I dare not infer from this that nothing ever will change. Let us try and see where these considerations lead. I have been here, ever since I began to be, my appearances elsewhere having been put in by other parties. All has proceeded, all this time, in the utmost calm, the most perfect order, apart from one or two manifestations the meaning of which escapes me. No, it is not that their meaning escapes me, my own escapes me just as much. Here all things, no, I shall not say it, being unable to. I owe existence to no one. Going nowhere, coming from nowhere.

As he does not attribute these lines to their source, the novel The Unnamable (1953) by Samuel Beckett, Smithson’s voicing of this first-person statement in an autobiographical film about his construction of Spiral Jetty implies that it is about himself. Despite Beckett’s straightforward declarative sentence structure and Smithson’s ponderous reading of it together evoking the quotation’s ‘utmost calm’, the rumination on existence is emotionally charged, fraught with more than philosophical discourse.

At the time, there was no reason to take Smithson’s insertion of this quotation as reflecting anything other than his own penchant for metaphysical arabesques. However, in the catalogue for the first exhibition of Smithson’s work after his death in 1973 (he was killed in an airplane crash while constructing the Amarillo Ramp), his widow, Holt, inserted a biographical fact that shifted the implications of Smithson’s adoption of Beckett’s claims. Smithson’s birth followed the death of his parents’ first child, Harold, at the age of nine-and-a-half from leukaemia. Death was haemorrhagic and swift; median survival was approximately six weeks.20

A week after the first anniversary of Harold’s death, the Smithsons conceived their second child, Robert. The timing indicates a parental desire to honour their survival of a year without Harold and to start again – to heal the family’s Broken Circle, as Smithson would title an earthwork in 1971 – replacing the lost child by conceiving another. Two days after the start of 1938, their new baby was born, regenerating their family triad. Smithson’s very existence was prompted by and entwined with the death of his predecessor. Characterised by psychologists as ‘replacement children’, the child arrives with not only with joyous love, but obligations, whether unstated or unconscious, to compensate. And inevitably, to compete – with a sibling who, being dead, can do no wrong. The existential coalescence of bereft parents, the memory of a dead child and the presence of a new child makes for complex circumstances in which each participant is awash in ambivalent regard for themselves and one another. The successor child commonly experiences a mixture of grief, gratitude, guilt and grudge for their sibling’s sacrifice.21

This biographical perspective affords Smithson’s use of Beckett’s lines an uncanny relevance: ‘my appearances elsewhere having been put in by other parties’ suggests Harold as his prototype, while ‘my own [meaning] escapes me’ evokes the family ghost, whose identity he cannot grasp, and the conflict with his own – between what was and what is. For anyone else, the assertion, ‘I owe existence to no one’ would be fatuous, but, considering Smithson’s early life, this declaration is at once a boast of autonomy and patently false. Chronologically and logically he owes his conception to his predecessor’s halted existence. ‘Survivor guilt is a common response in replacement children. Their life, they feel, is owed to the death of another’.22 Contrary to those conceived independently from the tragic death of a sibling, ‘Coming from nowhere’ does not exactly define his situation and neither does, for this inventive and literary artist, the idea that he is ‘going nowhere’. Both emphasise an arbitrariness rather than the deliberate nature of both Smithson’s birth and ambitious career trajectory.

At the beginning of his Oral History interview, Smithson jumped ahead chronologically to connect his dinosaur construction at seven to what he called the ‘prehistoric motif’ that ‘runs throughout’ his Spiral Jetty film: ‘So in a funny way I guess there is not that much difference between what I am now and my childhood’.23 For Smithson, his deceased brother and dinosaurs shared attributes: both were presences looming from ‘prehistory’ – geological and his own. Harold was a figure who existed prior to the beginning of his own life history and who, having been his parents’ only child for nine years, loomed large in family memory and importance – a fearsome competitor to a nominally ‘only’ child. Both dinosaurs and Harold were dead, and yet the number of Smithson’s visual and verbal allusions to the extinct beasts and coded references to his ‘secret partner’ suggest that for him neither were gone at all. Smithson remarked that he had ‘a kind of tendency toward the prehistoric after digging through the histories’ and ‘the entire history of the West was swallowed up in a preoccupation with notions of prehistory and the great prehistoric epics’.24 Both phrases picture a family overcome with thoughts of their own prehistory: the nine years with the first son and their ‘prehistoric epic’ with his tragic, wasting death before starting a new family history with their next son, Robert.

Smithson’s remark that ‘our future tends to be prehistoric’ may be taken as a zany literary conundrum; it is an elaboration of his frequent quotation of Vladimir Nabokov’s line ‘The future is but the obsolete in reverse’.25 But like many of his statements, it masked his psychological acuity and its autobiographical source. In the future, he would repeatedly configure his maps in terms of representing a connection to the past, stating about Spiral Jetty ‘I needed a map that would show the prehistoric world as coextensive with the world I existed in’.26 The world he lived in, metaphysically and psychologically, which included dinosaurs – and Harold – was a past not passed, as the titling of another now-lost painting from his 1959 exhibition attests, Living Extinction (1959).

The connection between Harold and dinosaurs is reinforced by a quotation which appears to have been so important to Smithson that he pinned a typed excerpt to a wall:

For some time Joey continued to draw dinosaurs. Indeed, the fascination of these huge extinct animals for many psychotic children is quite remarkable. Typically, they get interested in dinosaurs when they begin to guess what must happen if they are to lay the ghosts of their past: they must first exhume and put correctly together those skeletons in the closets of their minds; that they must understand what the skeletons meant when they still roamed through their lives. Freud likened the work of psychoanalysis to archeological discoveries. Maybe these children have found a better analogy than the reconstruction of dead buildings and artifacts from buried places. Their need is to unearth something that was once very alive, very huge and overwhelmingly stalked them.27

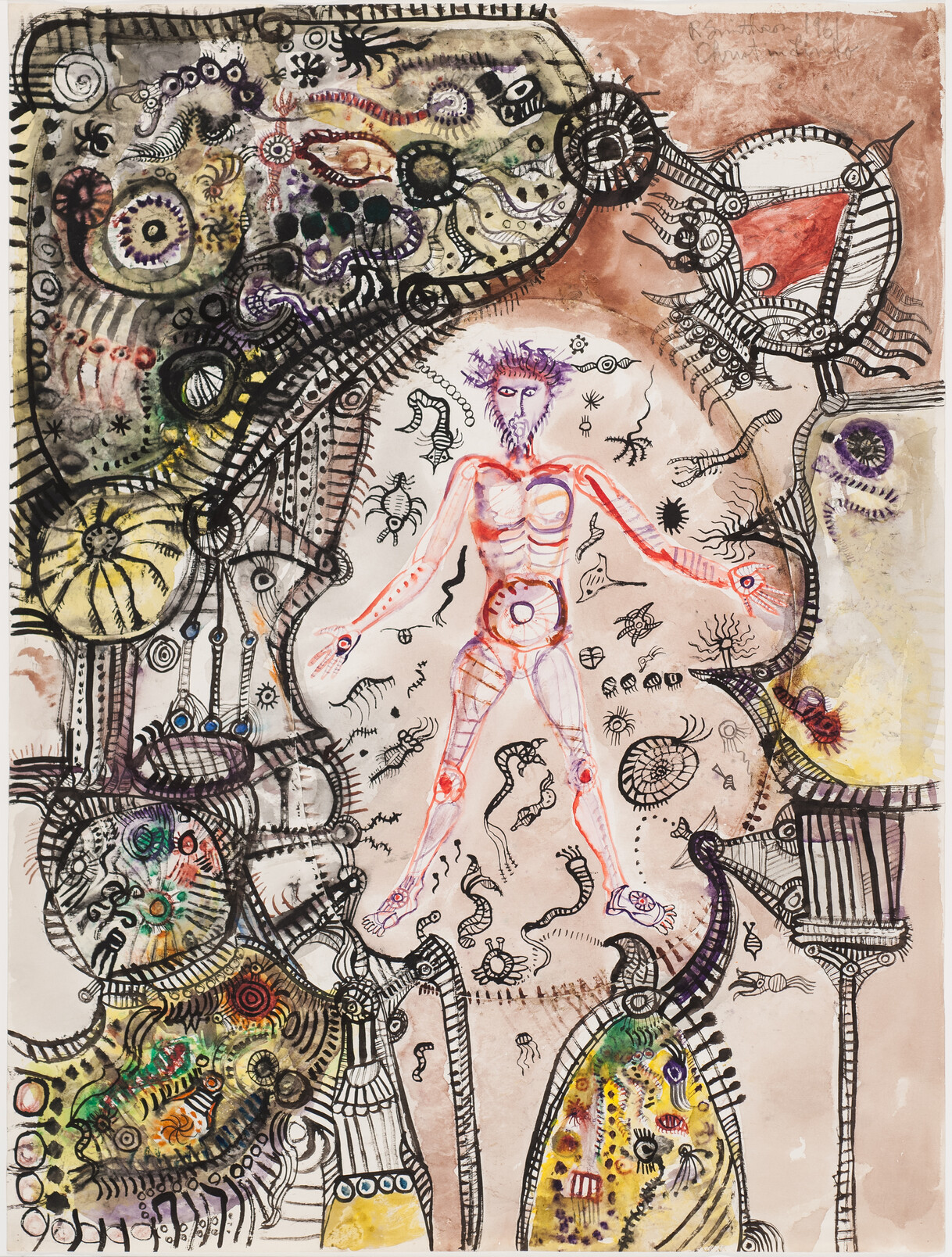

Smithson quoted a 1967 study by the Austrian-American psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, ‘The empty fortress: infantile Autism and the birth of the self’, in which he describes a young patient, Joey, ‘putting his fantasies on paper’, a process that Smithson – or any artist, implicitly – could relate to.28 He could have easily identified with Bettelheim’s Joey, similarly feeling ‘stalked’ by the predecessor ‘once very alive’, whose presence loomed ‘huge’ to the family, threatening to ‘overwhelm’ his own identity. Bettelheim continues, ‘in addition to being dangerous and huge, something that was once alive and is now dead [...] To Joey they also stood for something that is buried and can be dug up again’.29 In the early 1960s he painted creatures in subterranean spaces with titles such as Alive in the Grave of Machines (1961), Buried Angel (1961) and Christ in Limbo FIG. 12. At thirty-two he drew fragments of architecture mired in earth and produced the earthwork Partially Buried Woodshed (1970) at Kent State University, Ohio. Smithson piled soil on top of a cabin-like woodshed, engulfing it until its central beam collapsed. When Joey first encountered Bettelheim he was nine-and-a-half years old. As such, ‘Joey’ represents both Harold, in age, and Smithson, in his attachment to dinosaurs, evoking the common fusion of identities in replacement children.

To return to the dinosaur sequence in Spiral Jetty: the indistinct nature of Smithson’s knowledge of Harold is rendered in the beasts’ shadowy presence. However, he aids identification by photographing the dinosaurs through a red lens, which, in turn, corresponds to Beckett’s description of ‘unnamable’s’ eyes that ‘from the tears that fall unceasingly [...] must be as red as live coals’. Red is a colour necessarily associated with Harold’s haemorrhagic leukaemia. Thus, Harold is the ‘unnameable’ twofold: socially and emotionally. The extent of Smithson’s references to Harold – not just in relation to dinosaurs, but in other works and statements – indicates that his parents did not openly discuss their loss and put the issue to rest; he clearly learned from them that difficult issues were not to be discussed. Professionally, his containment was facilitated by the rejection of Abstract Expressionism’s uninhibitedness by artists in the 1960s; macho intellectualising sculptors did not speak of intimate conflicts. But also, the idea of the ‘unnamable’ suggests not the lack of a name but the inability to name it, something so traumatic that words fail, being unfathomable to oneself and unrepresentable to others – aspects associated with trauma.

Smithson’s attachment to dinosaurs was far more substantial than mere fascination with the huge reptiles still found in ‘shopping malls, theme parks, movies, novels, advertisements, sitcoms, cartoons and comic books, metaphors and everyday language’, as W.J.T. Mitchell notes in The Last Dinosaur Book.30 The literary scholar Richard Stamelman offers a compelling explanation for the repeated representation of loss:

We try to overcome loss by naming it, by representing it and by finding new forms and images through which to retell, recall, remember and resuscitate what has disappeared [...] surrogate objects that, standing in the place of what has disappeared, simultaneously memorialise its significance and mourn its loss.

For Smithson, dinosaurs were a means for a creative ‘“presentification” of absence’.31 Depicting these creatures allowed him to continue a relationship, however ambivalent, with his lost brother. Through his projection of Harold’s existence onto the ferocious beings – that in his mind were not at all extinct – he enacted both memorialising mourning and vitalistic remembering. In him, both Harold and dinosaurs lived.