Laughing has 1,000 mothers: the grotesque goddesses of Mary Beth Edelson

by Clelia Rebecchi • June 2023. In collaboration with Drawing Room, London • Journal article

Introduction

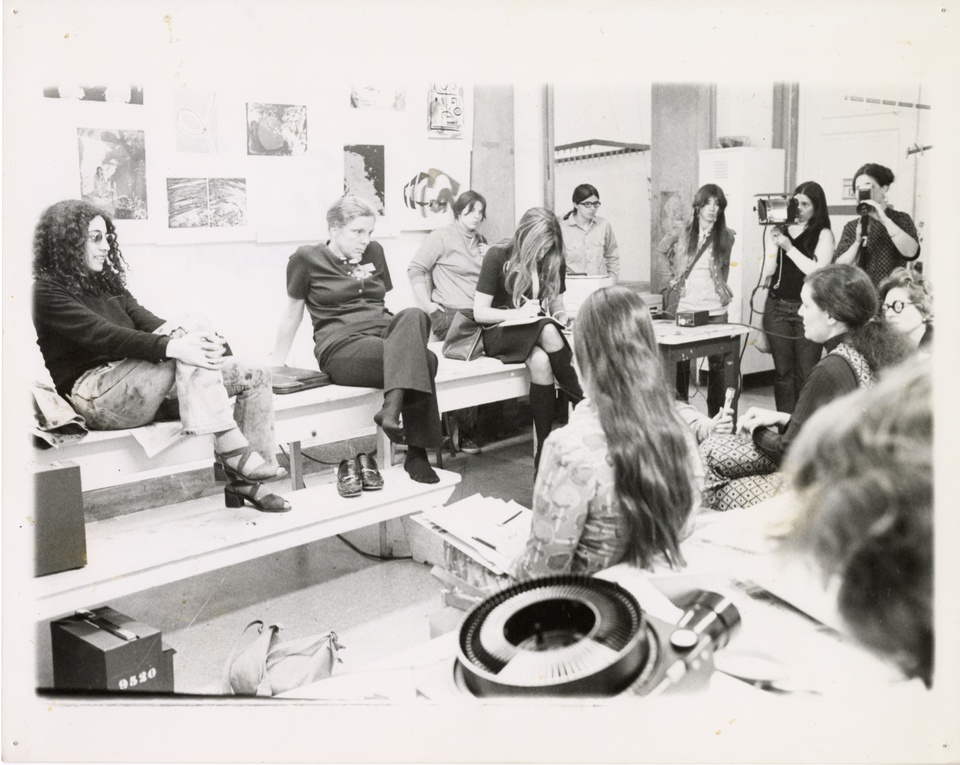

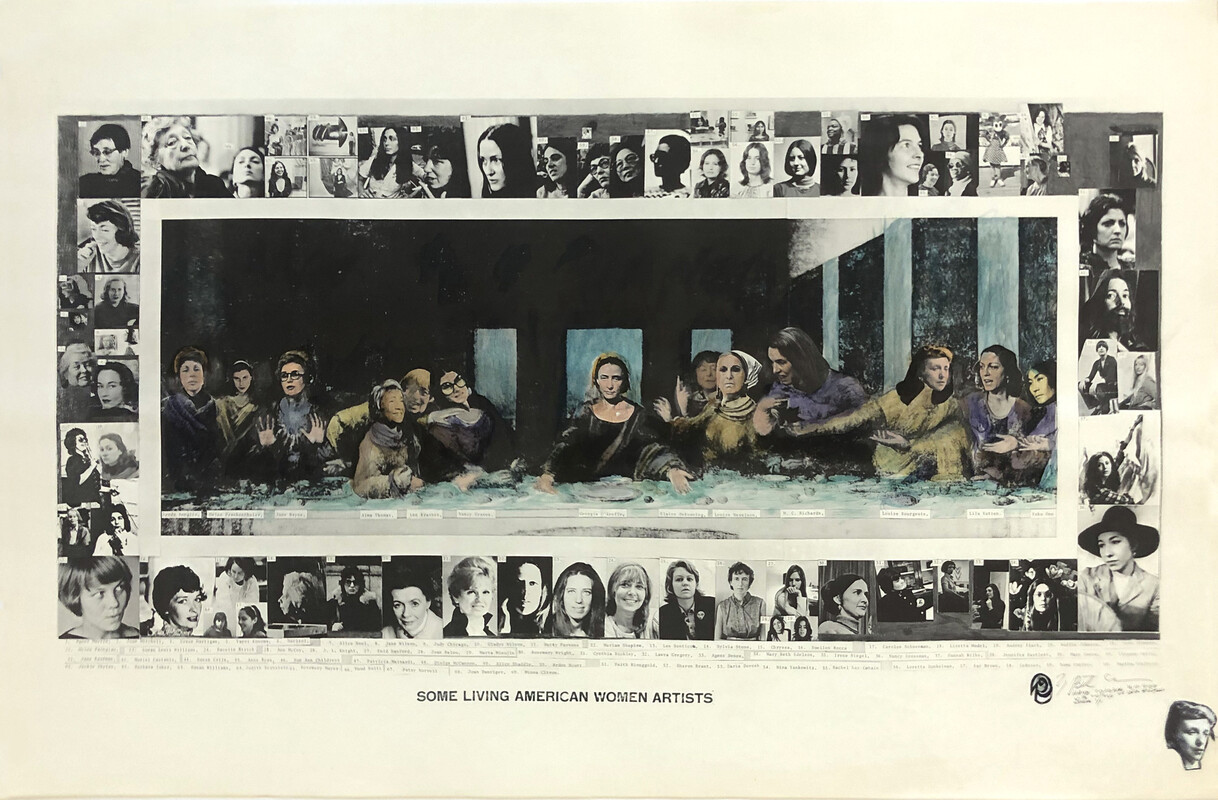

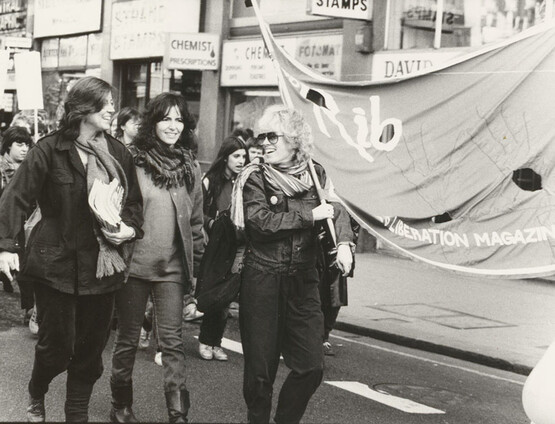

The American artist Mary Beth Edelson (1933–2021) was a leading figure of the feminist art movement. In 1972 she was one of the organisers of the Conference of Women in the Visual Arts held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, which constituted the first large-scale gathering of women in the arts FIG. 1. After working in Washington from the 1960s to the early 1970s, Edelson moved to New York in 1974 to join the newly formed A.I.R Gallery, a feminist collective that established an exhibition space for women artists outside of the male-dominated institutional and commercial art world. In 1976 Edelson was one of the nineteen founding members of the Heresies Collective, which produced a bimonthly journal dedicated to different feminist issues and, in 1992, she became an active member in the Women’s Action Coalition FIG. 2. These projects attest to Edelson’s belief in the sociopolitcal possibilities of art as a platform for feminist activism. Her output, which spanned five decades, comprises painting, drawing, body art, performance, photography and collage, and is underpinned by an ongoing interrogation of existing image culture and a quest for a new vocabulary with which to represent women.

Edelson is often associated with goddess spirituality, a belief that proliferated in the United States throughout second-wave feminism, and which the artist espoused visibly in her practice. Edelson’s works relating to goddesses are motivated by a belief in the potential of myth for feminist struggles and by the role of mythical imagery in the construction of both individual and collective identities. This article investigates two photographs, Jumping Jack Sheela (1973) and Trickster Body (1973), both of which belong to Edelson’s Trickster Series (1973), a body of photographic works in which the artist attempts to redefine women’s image culture through an appeal to goddess imagery.1 The article teases out the variety of formal strategies and vocabulary that Edelson adopted in her goddess works, which have remained largely underexplored, in order to better chart her contributions to feminist art history and map her works within broader art-historical and theoretical currents.

Despite being a dominant figure in feminist art, celebrated by such figures as Lucy Lippard, Jack Burnham and Laura Cottingham, Edelson’s critical reception and presence in the art establishment have suffered from the negative criticism directed at goddess spirituality, which has dominated feminist academia since the 1980s.2 Strategies associated primarily with goddess spiritualism, including the celebration of women’s naked bodies and the positive reclamation of so-called ‘female qualities’ and ‘attributes’, came under attack for promoting essentialising views of femininity that naively asserted the existence of an innate feminine identity that had a locus in the female body.3 Such feminist strategies were said to uphold existing dichotomies between male and female instead of challenging any innate biological determinism.4 Rather than a positive re-evaluation of femaleness, feminists in the 1980s – particularly those in academia – called for the dismantling of power dichotomies through a deconstructive strategy informed by psychoanalytical and socialist theories. In art, this translated into an ironic or textual approach, where depictions of women’s naked bodies became a taboo.5 As Miwon Kwon later claimed, the crux of the issue was ‘the body as a transparent signifier of identity versus the body as a nexus of arbitrary conventions’.6 In contrast to goddess feminism and so-called ‘cultural feminisms’ (thus called because it allegedly encouraged the creation of a separate woman’s culture), the constructivist position expanded upon throughout the 1980s described the body and identity as effects of sociocultural contingencies, understanding categories like the feminine as functions of systems of representation. In art, this position resulted in the vast problematisation of the portrayal and celebration of women’s bodies. Within this climate, goddess art was accused of endorsing a naive and disengaged female counterculture that lacked a critical approach to women’s representation and evaded feminist struggles.

The overdetermination of goddess art within essentialising tendencies has partly overshadowed the contributions to the feminist movement that are evident in Edelson’s goddess images and has resulted in the wider obscurity of her work. This article adopts feminist readings of Freudian psychoanalysis, informed particularly by the writings of Barbara Rose and French psychoanalytic feminism, to shed new light on the feminist strategies used in Edelson’s goddess art. Although the artist was not known to be interested in the psychoanalytic writings of Freud, the present author contends that her works deconstruct the concepts of castration anxiety and fetish and, through their use of humour and the grotesque, anticipate the writings of Hélène Cixous and Mary Russo’s feminist reading of Mikhail Bakhtin. Considering Edelson’s works in this way facilitates a shift in the discussion of her goddess imagery away from the essential female body towards an appreciation of her deconstructive strategies.

Edelson’s iterations of goddess imagery range from a lyrical language to a humorous and parodic tone; this humour should be considered one of the main feminist strategies of disruption pioneered by the artist. Her rendition of the goddess in the Trickster Series unveils a comic sensibility in which the carnival grotesque and the exaggerated display of female genitals come together as deconstructive tools, eliciting a subversive carnivalesque laughter. Through this lexicon of humour, Edelson’s works complicate constructions of femininity and mockingly assault the phallocentric grammar of psychoanalysis and its production of female subjectivity. Edelson’s grotesque and parodic rendition of the goddess celebrates a pleasurable form of female exhibitionism and appeals to a communal laughter that crosses centuries to bring women together in solidarity and hilarity. Focusing on Edelson’s humorous strategies highlights the different ways in which goddess imagery permeated women’s art and opens new lines of inquiry into the contributions of feminist spiritualism to feminist art history.

‘Woman Rising’: reclaiming herstory

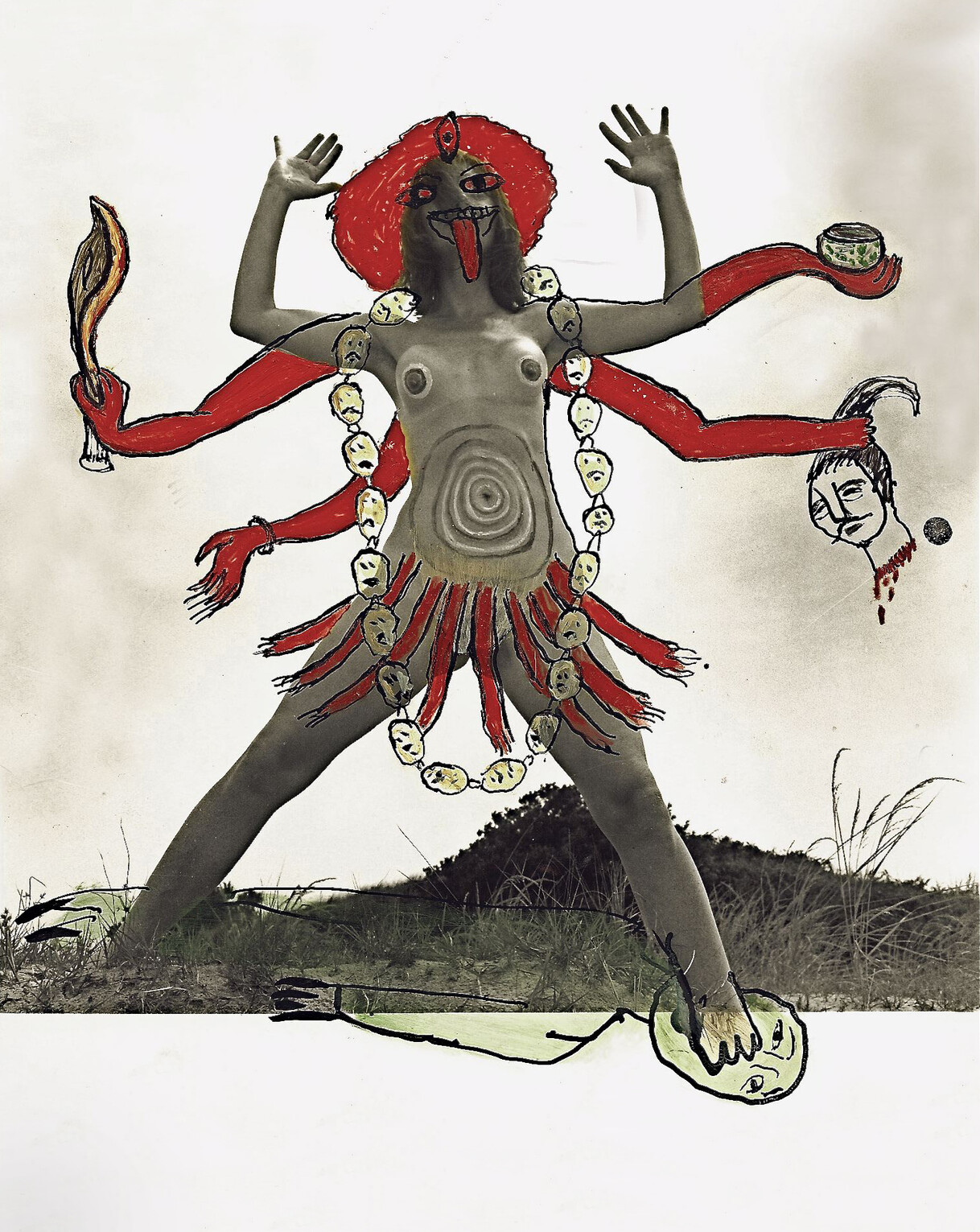

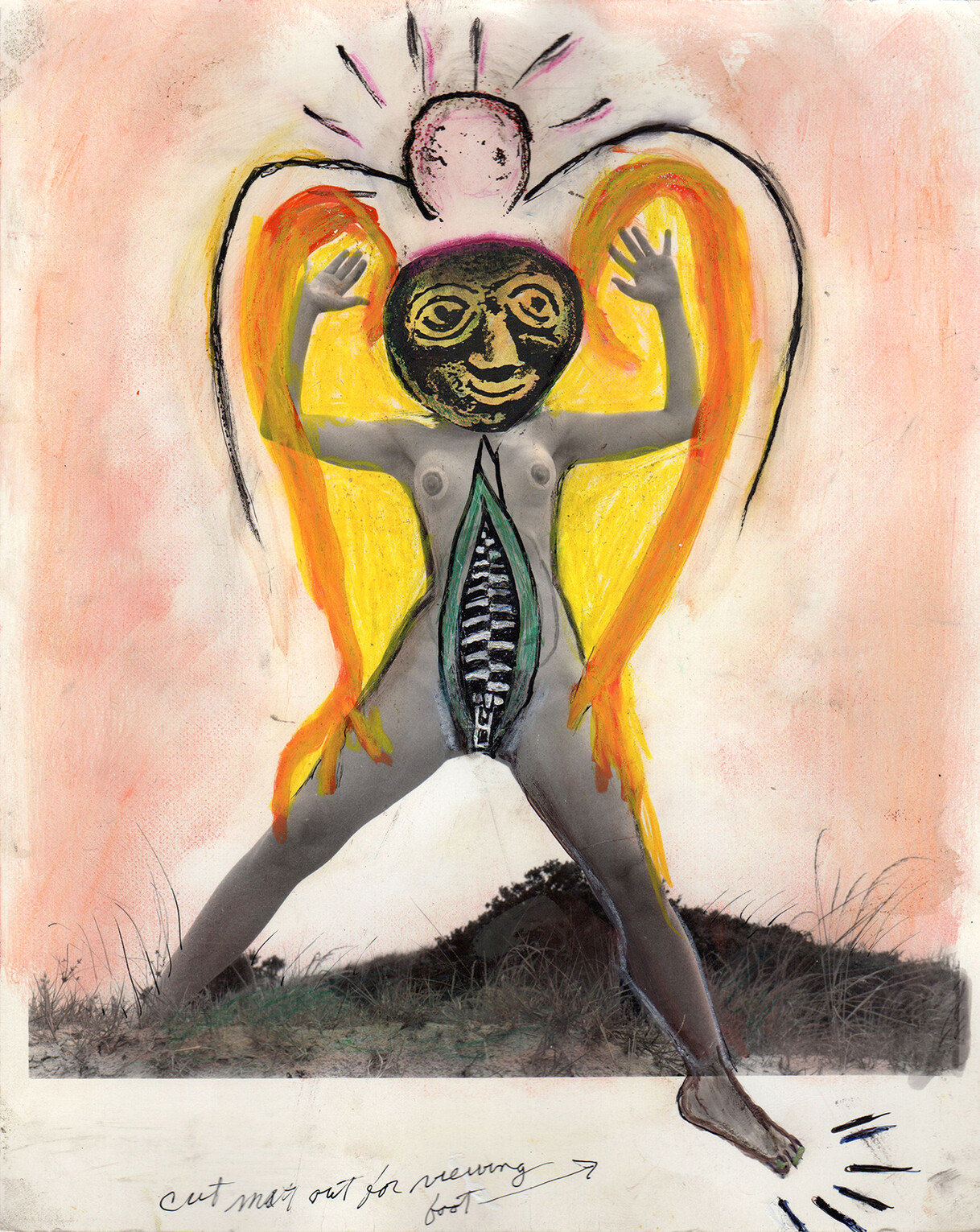

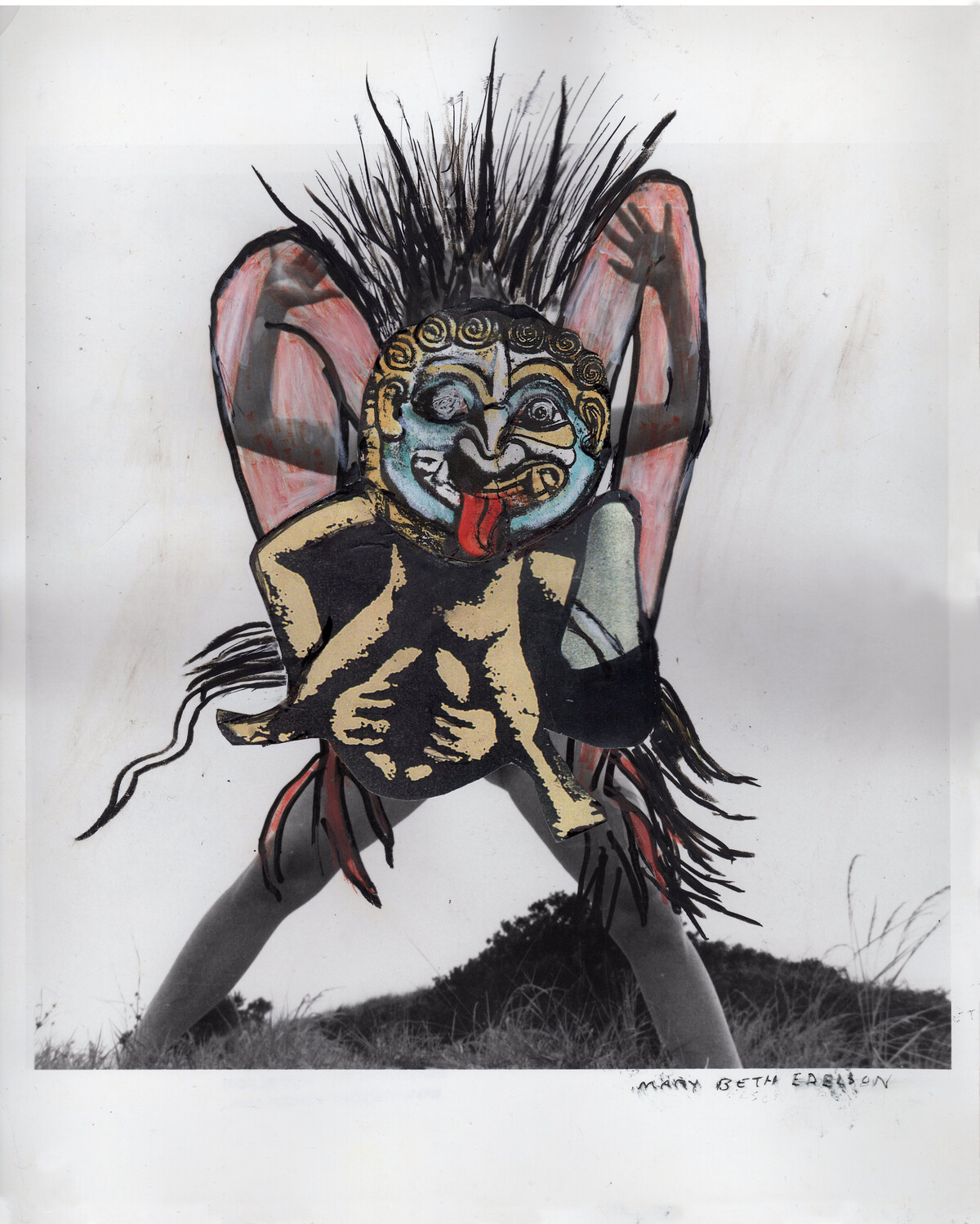

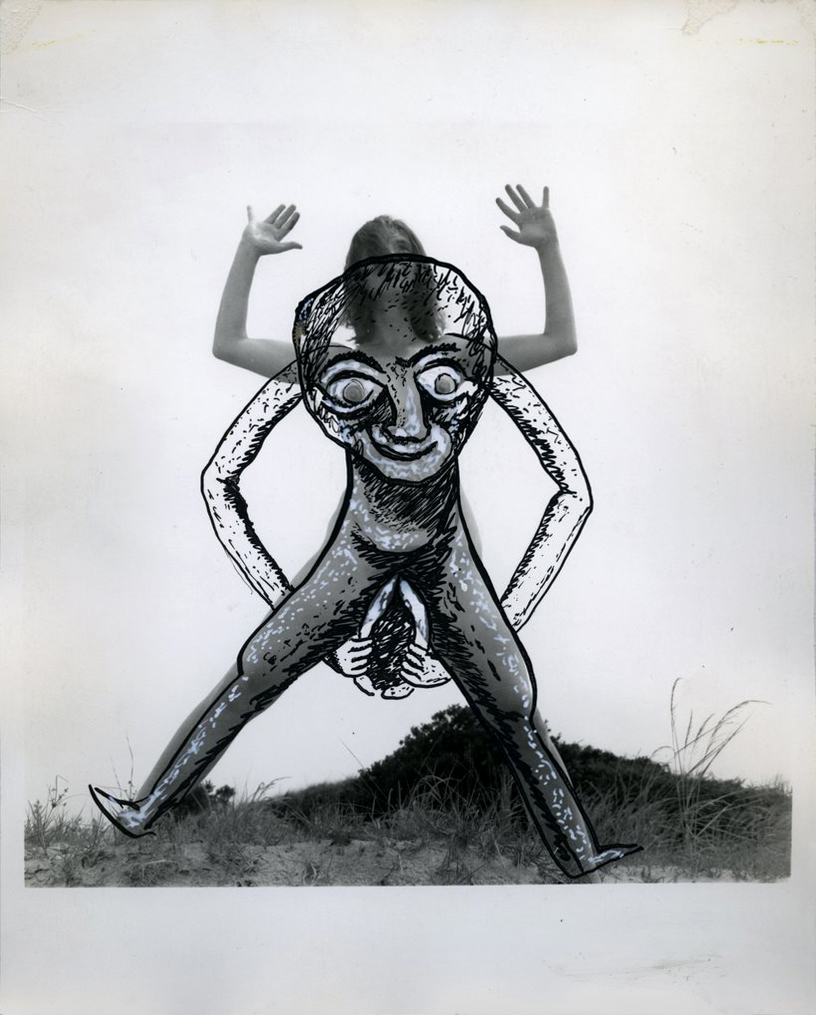

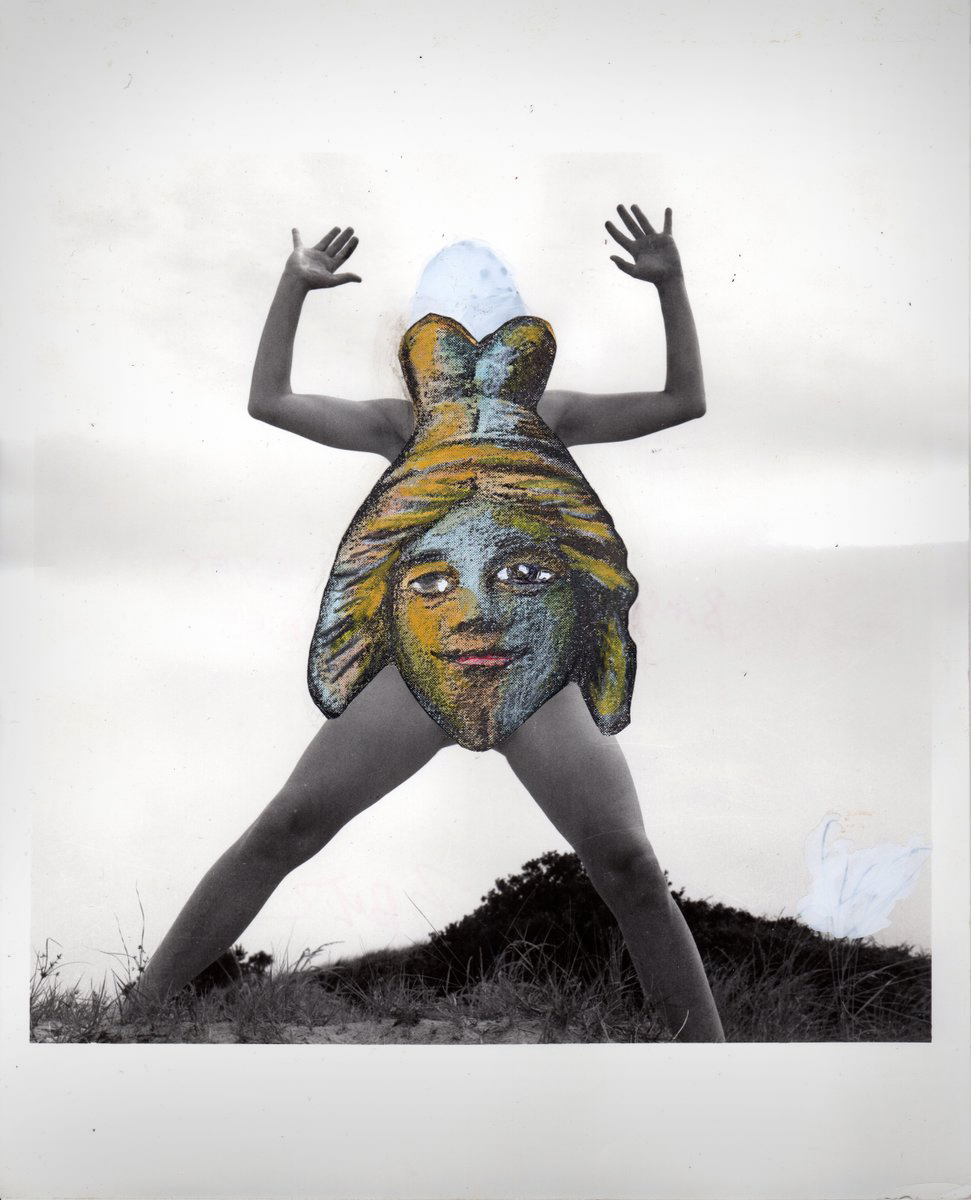

The Trickster Series consists of visual superimpositions, through ink or paint, on a repeated photographic image printed on silver gelatin. Edelson produced the series in 1973 following a private ritual performed in Outer Banks, North Carolina, which she recorded on 35 mm film. Edelson printed the photographic documentation and duplicated it multiple times, drawing different mythical figures or goddesses on each photograph. The resulting pantheon of goddesses, drawn from the writings of Marija Gimbutas, Robert Graves and Erich Neumann, is transnational and transhistorical.7 The goddesses included the Hindu Kali FIG. 3, the Greek Baubo and the Celtic Sheela-Na-Gig FIG. 4. Whereas some images only represented one goddess at a time, others creatively mixed elements from different deities to create hybridised figures FIG. 5, at times juxtaposing them with real-life figures like the critic Lucy Lippard or the artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) FIG. 6.

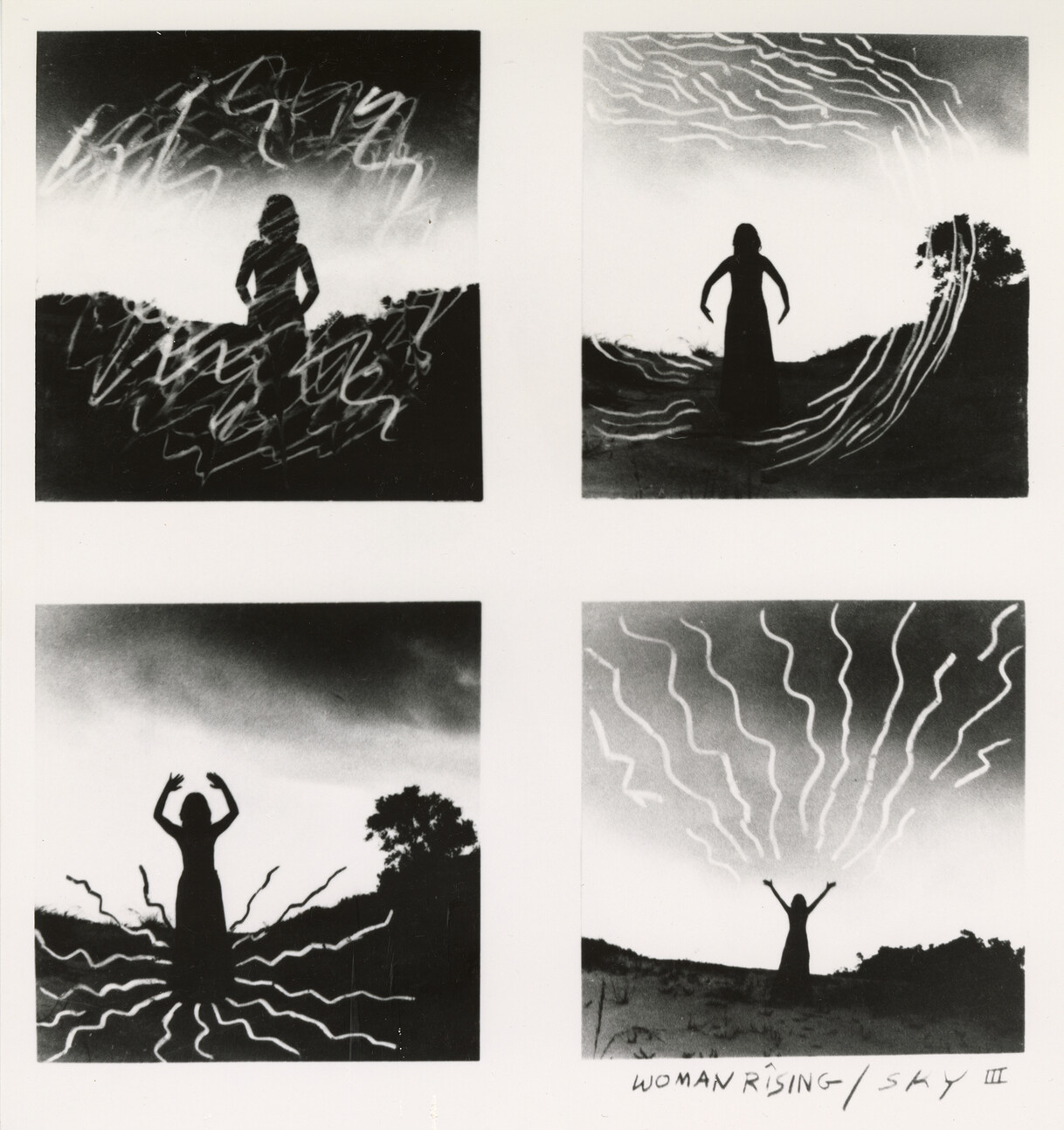

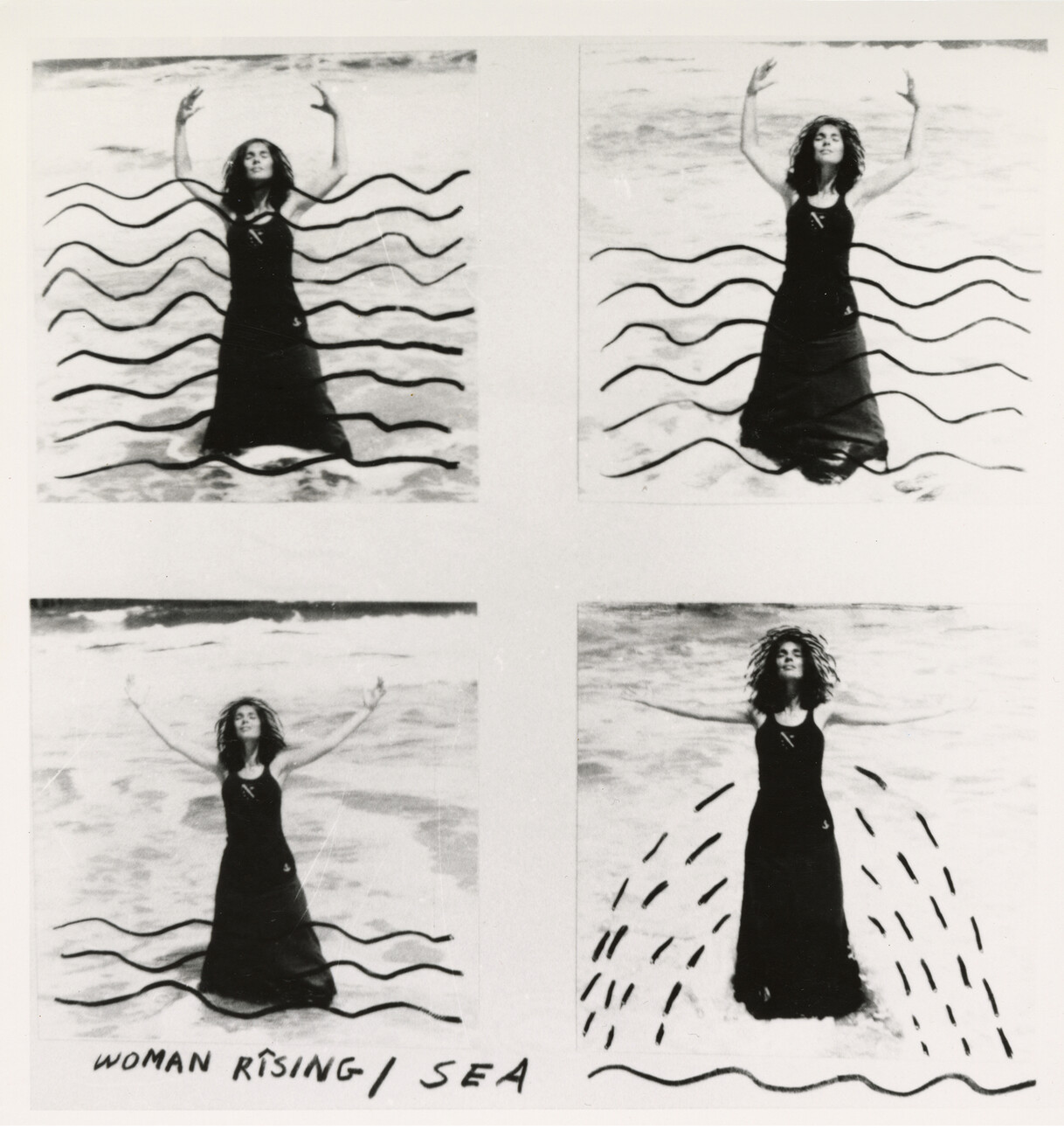

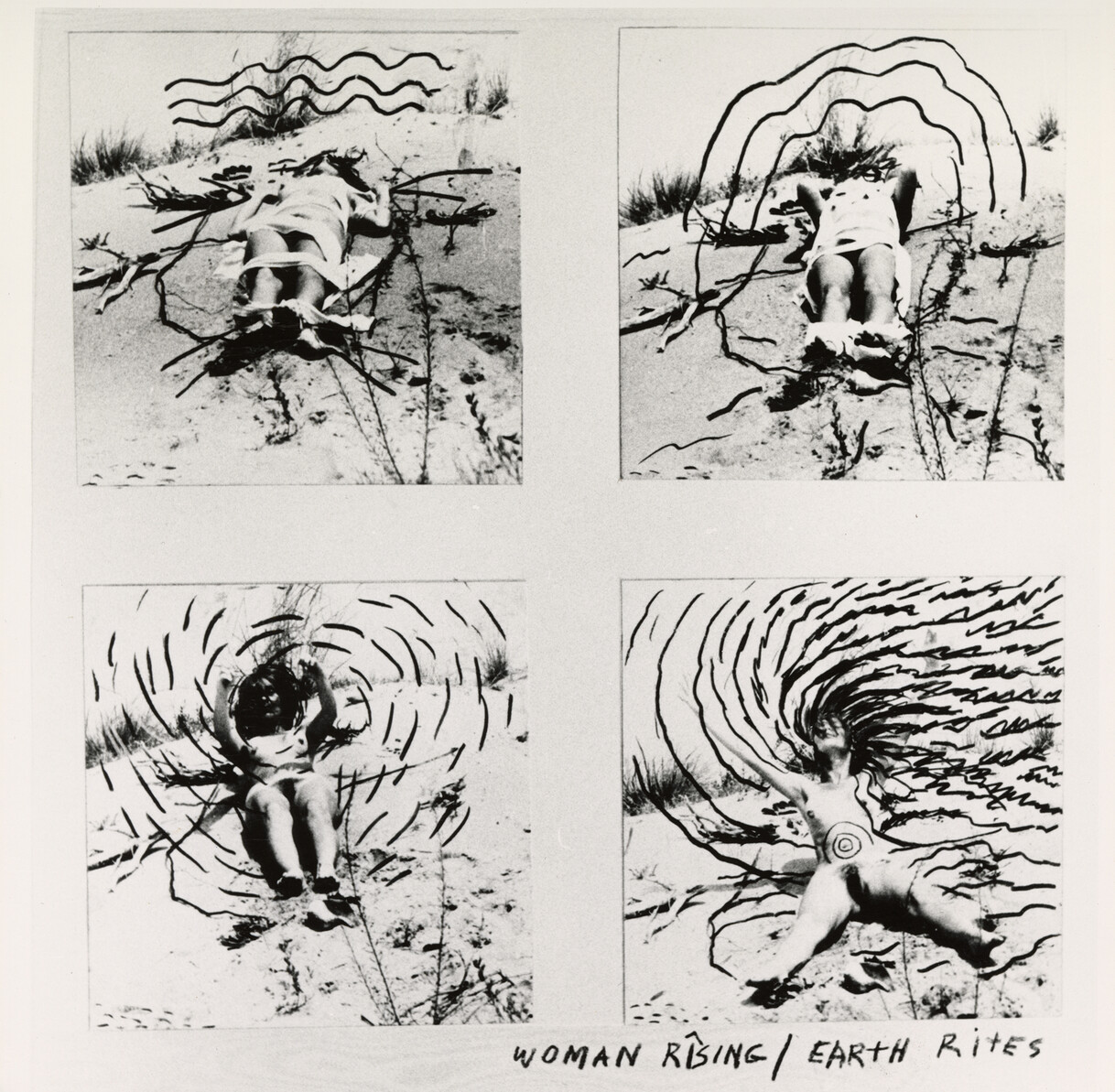

The performance that was photographed and used as the basis for the Trickster Series belonged to a larger ongoing ritualistic project titled Woman Rising FIG. 7, which marked Edelson’s shift from painting to performance, a medium that she considered better suited to articulate the ethos of feminism and feminist spirituality. According to the artist, performance and body art had the capacity to bring together the spiritual focus on ritual as a gateway to a metaphysical experience of the union of mind, spirit and the (female) body:

After 18 years, suddenly I stopped painting because it went stale for me. I wanted more direct ways of communicating with people […] these images were defining images – not who I was but who we are – the spirit of what liberation felt like in bodily form as mind / spirit / sexuality all in one, presented assertively.8

Set in a pristine natural landscape, the Woman Rising photographs, the only documentation of the performances, show the artist striking sculptural poses, at times fully naked and at times wearing a dark dress FIG. 8.

The belief in the goddess was a central, guiding metaphor for these rituals. In the photographs, Edelson presented herself in the guise of the ‘Great Goddess’ to create a universal image that could speak, in the artist’s words, ‘of women’s powers’.9 In the Trickster photograph, Edelson posed naked in a deserted natural landscape, her hair flowing over her face, her legs spread apart and her hands upraised in a sculptural pose. The concentric dark and white circles painted on her naked chest and abdomen were a gesture acknowledging the power that the artist attributed to women’s bodies.10 Edelson, whose silhouette occupies most of the photograph, presented the female body as a source of power, freedom and pleasure, while the natural landscape around her suggests the complicit interconnectedness between women and nature, which feminist spirituality vocally espoused.

The artist’s authoritative pose spoke to the unleashing of women’s potential and referenced the freedoms many women found in the 1970s.11 In describing Woman Rising, Edelson stated that she aimed to make a symbolic image for women ‘that says I am, and I am large, and I am my body, and I am not going away’.12 Through this emphasis on women’s bodies and sexualities, Edelson explored a theme that would become a defining one for many feminist writings of the time, and that is perhaps best articulated in the work of Cixous. In 1975, two years after Edelson’s performance, Cixous wrote ‘The laugh of the Medusa’, which many have called a feminist manifesto.13 In it Cixous advocated for the creation of an écriture feminine, a form of writing derived from women’s differential experience of pleasure and drawn from their libidinal body.14 Cixous claimed that women needed to start speaking of pleasure to extol a female sexuality and unleash women’s powerful creative force. While admittedly for Cixous it was through writing that women should assert this jouissance and break free from patriarchal narratives, many women such as Edelson found a comparable tool in performance, and particularly feminist ritual FIG. 9, with which to engage in a process of self-discovery. As a new medium, freed from the conventions of a male-dominated history of art, performance was seen as a particularly fruitful arena for feminist explorations, one that, like Cixous’s écriture feminine, saw the libidinal, sexual female body as the locus of women’s liberation. In this spirit, Edelson’s performances laid a political claim on women’s ability to reclaim their sexualities and their bodies, and offered a lyrical and empowering celebration of female pleasure and power, aptly capturing the spirit of a new generation of feminist consciousness.15

In the Trickster Series, Edelson elaborated on the language she used in Woman Rising, adding a new, material layer of meaning through the superimposition of ink and photographs that exhumed a pantheon of defiantly deformed and exaggeratedly promiscuous female characters, appropriated as goddesses under the aegis of feminism. Rather than a lyrical celebratory tone that emphasised the sacred power of women’s bodies, the Trickster Series used a deconstructive and carnivalesque lexicon of humour. This humorous language allowed Edelson to reclaim a pleasurable female sexuality and affirm women’s exhibitionism while also comically deconstructing phallocentric constructions of femininity. In this sense, the lyrical and mystical tone of Woman Rising that celebrated the beautiful and powerful female body was left behind in favour of a comical strategy that affirmed women’s stake on their sexuality by means of mockery and critique. The juxtaposition of Woman Rising and the Trickster Series suggests the array of strategies deployed by the artist to address the struggle of women’s historical representation and offers insightful material on the multifaceted materialisation of goddess spiritualism into women’s art.

Edelson’s lexicon of humour: the carnivalesque and the grotesque body

In the Trickster Series, Edelson engaged in an archaeological excavation of female power and imagery to reclaim women’s myths. In Jumping Jack Sheela FIG. 10, Edelson turned to the Celtic fertility deity Sheela-Na-Gig, who was transformed in a Christian context into an apotropaic grotesque figure. Sculptures of her were often used in churches as a means of guarding the faithful against the dangers of sinful lust and female pleasure. In Trickster Body FIG. 11, Edelson invoked the Orphic Baubo, a figure celebrated during the Greek festival of the Thesmophoria. Edelson’s rediscovery of these mythical figures fits within the retrieval of women’s lost herstories in feminist spirituality. As part of its agenda, feminist spiritualism offered not only an alternative to patriarchal religions but also attempted to recover a female-centred symbolism that could allow women to better negotiate their place in history and reclaim their rights in the present. This led to a positive valorisation of supressed images, from prehistoric fertility statuettes to the ostracised hags and witches, which became a powerful symbol of feminist resistance. Edelson incorporated such figures in her Memorial to 9,000,000 Women Burned As Witches during the Christian Era (1977), a collective performance carried out at A.I.R Gallery in remembrance of the witches executed during the rise of Christianity.16

Edelson had already carried out elements of this critique in the large collage Some Living American Women Artists FIG. 12 and again later, in its most articulated development, in the performance Grapceva Neolithic Cave See for Yourself FIG. 13. In Some Living American Women Artists, Edelson criticised Christianity for its denial of access to positions of power for women and commended the works of sixty-nine women artists, who are presided over by Georgia O’Keeffe in the guise of Christ. In See for Yourself, Edelson travelled to a cave in what was then Yugoslavia (now Croatia) after reading Gimbutas’s The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, in which the scholar identified Yugoslavia and the Balkan region as an area of early goddess worship and matrifocal cults.17 Edelson sat down naked in the centre of the cave and recorded her ritual using a time-lapse technique, creating a ghostly photograph in which the trace of the artist’s movements evokes otherworldly presences interacting with her body.18

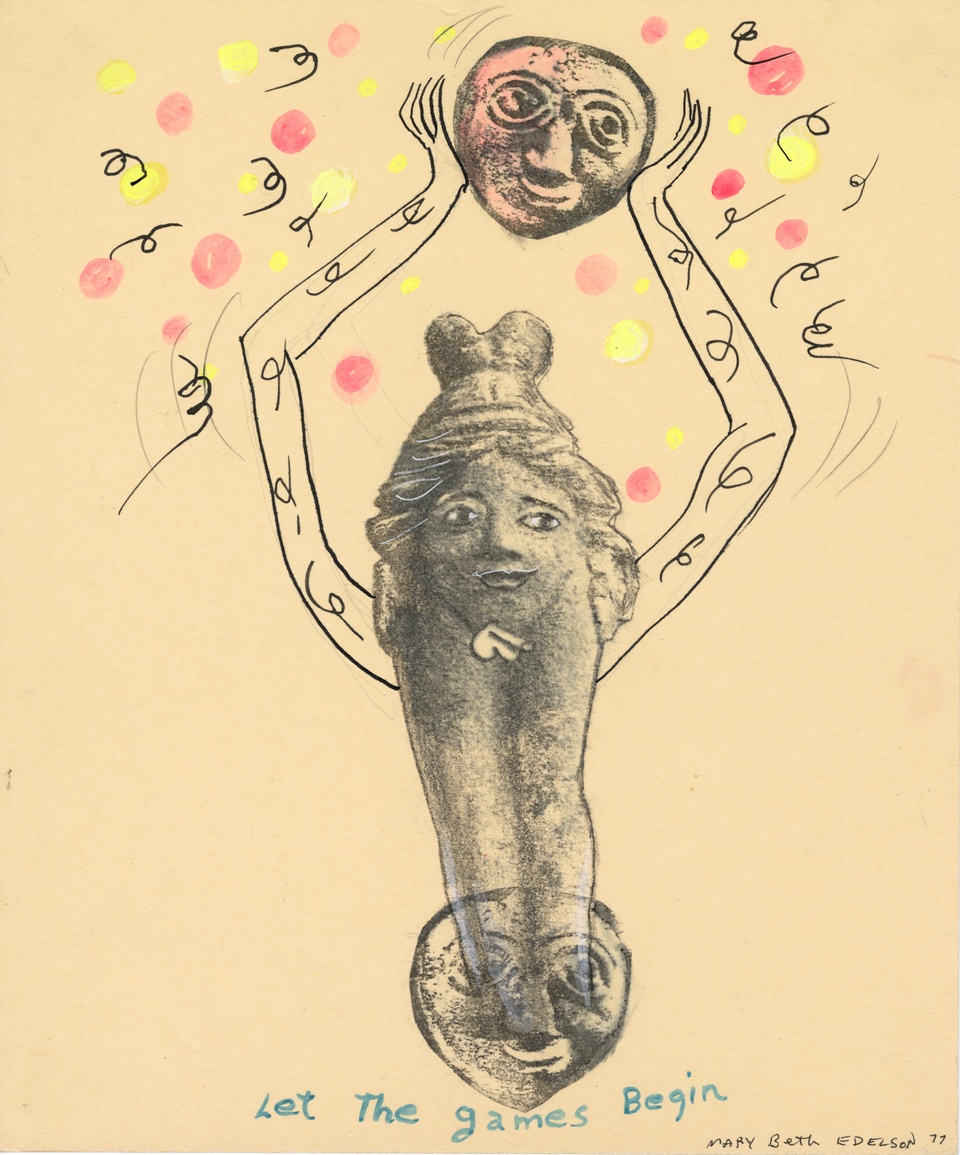

In the Trickster Series, Edelson articulated this investigation into women’s herstories with a comic sensibility, which is evident in the parodic rendition of the goddess as the confrontationally promiscuous and anatomically warped Sheela-Na-Gig and Baubo. Edelson drew this iconography from a long visual tradition of portraying Sheela and Baubo in the act of anasyrma: the revealing of the genitals. In the Sheela-Na-Gig image, the exaggerated display of the vulva connects to her role as a fertility goddess associated with life-giving powers, who through her gesture assisted and protected women during labour.19 Baubo’s iconography derives from Greek myth.20 After Persephone’s abduction on behalf of Hades, Demeter – Persephone’s mother and the goddess of harvest and agriculture – travelled across Greece looking for her daughter in despair. One day, Demeter encountered the old woman Baubo, who, upon seeing the sadness on Demeter’s face, lifted her skirt to reveal her genitalia, provoking Demeter’s laughter for the first time since Persephone’s disappearance. This story is often playfully illustrated by the conflation of Baubo’s head and abdomen in representations of her.21

Following these iconographical traditions, both Jumping Jack Sheela and Trickster Body call attention to the female genitalia and, in the latter, to the particular conflation of Baubo’s head and body. In Jumping Jack Sheela, the focus is the defiant gesture of Sheela, whose hands ostentatiously guide the viewer downwards while she smirks confrontationally. In Trickster Body, Edelson’s own head is faded, while on her abdomen Baubo’s head-genitalia looks at the camera, smirking in a similar manner. This exaggerated focus on the lower parts of the body of both Sheela and Baubo, together with their defiant gaze and wry expression, contribute to their comic appearance and situate their visual portrayal within the realm of the Bakhtinian grotesque and carnivalesque. The grotesque body is the body of the medieval carnival. In Rabelais and His World (1965), Bakhtin maintained that the carnival represented a temporary site of insurrection characterised by the comic and festive mocking of hegemonic narratives.22 It used parodic and satirical humour to subvert what was oppressive about everyday structures, disrupting the conventions and powers of society through play.23 The carnivalesque laughter proliferous during these moments of liberatory transgression was equally radical, rebellious and freeing: ‘gay and triumphant, and simultaneously mocking and deriding’.24 In tandem with the carnival’s comic inversion of high and low, the grotesque body violated the norms of Classical beauty. Whereas the Classical body is self-contained, polished and well-proportionate, the grotesque body is defined by a logic of excess and disproportion.25 The grotesque focuses on the lower parts of the body and emphasises features associated with excess, such as the belly, orifices and genitals.26 It is the body of pleasure, of debased carnal, sexual and ravenous instincts and appetites, whose transgressive incontinence was turned into the source of communal amusement and carnivalesque laughter.27

The grotesque body of the carnival is also the body of Sheela and Baubo. With her conflated head and abdomen, Baubo embodies Bakhtin’s remark quite literally and also visually recalls the laughing hags found in the ‘famous Kerch terracotta collection’ that he takes as emblematic of the female grotesque.28 Likewise, the fertility goddess Sheela represents grotesque orifices through an exaggerated, centralised void that lures the viewer in. When exhibited together, Edelson’s goddess-monsters create a festive procession reminiscent of carnival entertainments. In this way Edelson’s intentional choice of particular grotesque characters from an extensive pantheon of goddesses signals her intent to explore a broader vocabulary of women’s images, foregrounding the grotesque and the carnivalesque as an arena of possibilities for feminist aesthetics.

Edelson’s writings further locate her use of humour within the domain of the Bakhtinian carnivalesque. Although she never referenced the carnival directly, Edelson repeatedly stated that Sheela and Baubo embodied two manifestations of the trickster archetype, which allowed her to humorously suggest notions of female uncontrollability.29 The trickster is discussed by Carl Jung as a being a mythical creature, half-divine and half-animal, and distinguishable through its folly and wit.30 The Jungian trickster is the bearer of chaos, but it is also the unfiltered voice of truth, which interrupts and critiques any authoritative narrative.31 Not unlike the role of the carnival, the voice of trickster – here in the guise of Baubo and Sheela – makes fun of and exposes hegemonic paradoxes through an appeal to laughter.

In The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (1986), Peter Stallybrass and Allon White explain the carnivalesque as a political demystifying instrument that can unsettle and expose the oppressiveness of hegemonic dogmas through humour: ‘The carnivalesque laughter and carnivalesque inversion deny with a laugh the pose of autonomy adopted by the subject within the hierarchical arrangements of the symbolic’.32 At play in Edelson’s portrayal of grotesque bodies is precisely this return to a carnivalesque humour to irreverently disrupt patriarchal authority and affirm women’s claim on pleasure and sexuality. Edelson’s Trickster Series deploys old myths to resurrect Bakhtin’s carnivalesque laughter to suggest a pleasurable, uncontrollable and subversive investment in women’s bodies. At stake in these goddess images, therefore, is an understanding of carnival humour as a way to break the hold of phallocentrism to reclaim women’s libidinal body with a liberatory and rebellious laugh.

What is so scary about castration? Edelson’s deconstructive use of humour

The Trickster Series utilises the disruptive potential of carnivalesque humour to contest external authority and to open up this irreverence to play. In particular, Edelson’s grotesque goddesses undo the construction of the idea of woman in psychoanalytic thought, dismissing men’s castration anxiety and the way it generates a fear of women’s bodies. Edelson’s focus on women’s genitalia connects to the broader context of 1970s trends in feminist art, for which the motif was a central one. Lisa Tickner considered this new iconography to be one of the key strategies adopted by artists to signal the celebration of women’s mark of otherness, a characteristic that was fundamental, for instance, to the art of Judy Chicago.33 Within this context, the mythical figure of the Sheela-Na-Gig and her promiscuous gesture was increasingly reclaimed by women artists, figuring prominently in the production of Nancy Spero and in Cathleen O’Neill’s Millennium Poster, The Spirit of Woman. Edelson similarly adopted the sexual focus of Sheela and Baubo’s iconography as a powerful tool to celebrate female pleasure and jouissance.

Responding to these trends in art, Barbara Rose argued that such iconography refuted the Freudian concept of penis envy and the notion of ‘woman as the dangerous sex’.34 In his psychoanalytic writings, Freud defined ‘woman’ as a lack, in relation to men’s genitalia.35 During the Oedipal phase, the realisation of this lack by a young boy creates a castration complex and results in a fear towards women’s genitals, which is mitigated through the creation of a fetish.36 The fetish represents an object of replacement for the lost maternal penis that soothes men’s anxiety. The castration complex and the resulting fetishistic splitting result in women becoming the inert recipients of an objectifying and sexualising gaze that displaces men’s anxiety by giving the impression of mastery. In the Trickster Series, the reclaiming of the female sex through an appeal to the grotesque, instead, forces Freudian psychoanalysis to confront precisely what is scary about women, deriding men’s castration complex and disallowing the ensuing fetishisation of women.

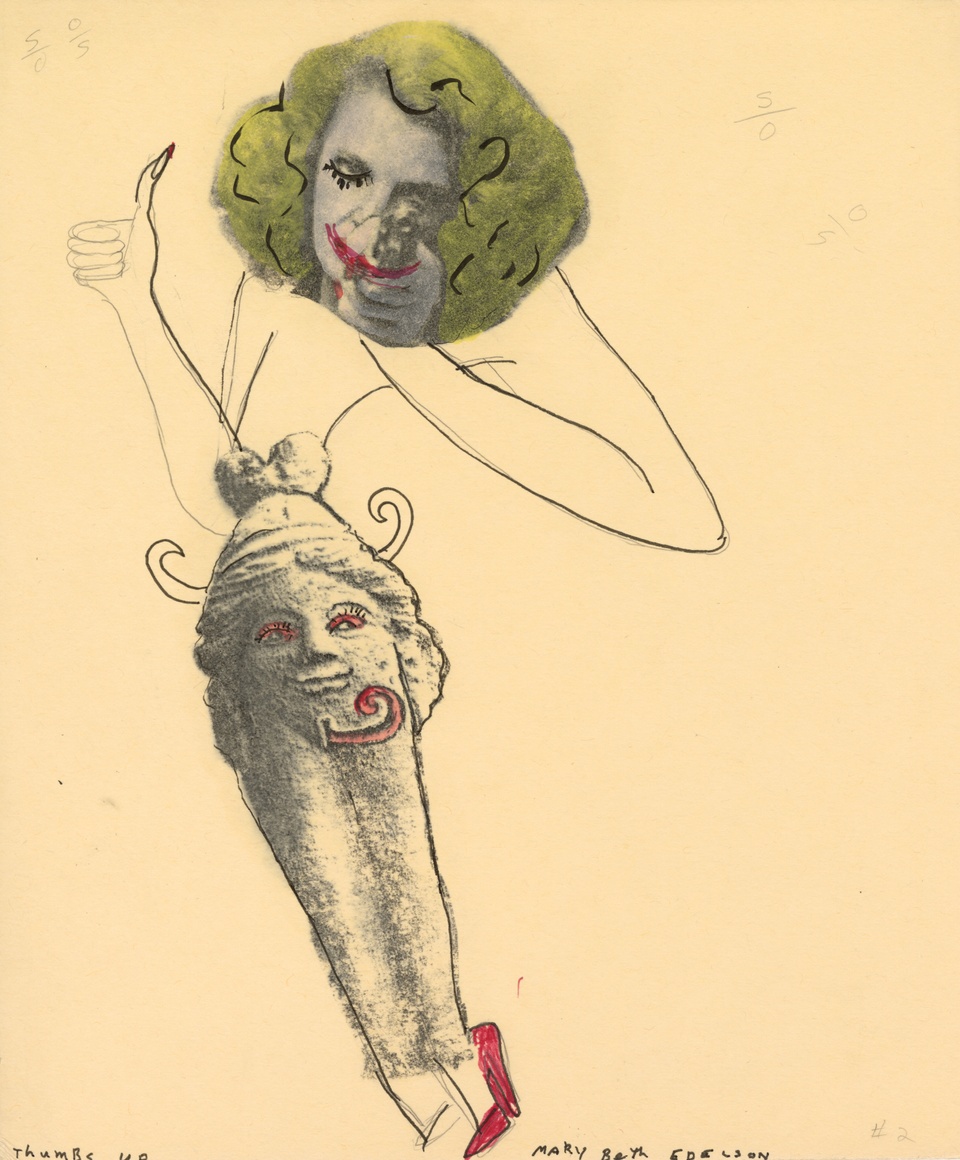

This humorous deconstruction of the castration complex is evident in many of Edelson’s goddess works. In Thumbs Up / Subject as Other FIG. 14 Edelson conflated a drawing of Baubo with an image of one of the women from her Shooter Series (1993). The woman points a gun at the viewer and Baubo looks suspiciously to the right, her coiled tongue playfully inviting male viewers to look exactly at what they fear the most. In another drawing, Let the Games Begin FIG. 15, Edelson switches up Baubo’s traditional iconography by portraying her with male genitalia as she playfully juggles two Sheela heads, evoking Freud’s alleged female envy only to deride it.

In a piece of writing from 2005 Edelson confirmed this purposeful denial of the castration complex by quoting Hilary Robinson, who identified in Baubo ‘a potential alternative to the castrating display of Medusa’.37 Cixous famously concluded ‘The laugh of the Medusa’ by claiming that Medusa is not scary, ‘she is beautiful, and she is laughing’.38 Medusa had become the symbol of the phallocentric misappropriations of female myths. Freud’s 1922 On the Head of Medusa has transformed her, and by extension all women, into the embodiment of profound lack.39 For Freud, Medusa became the symbol of men’s castration anxiety; while it is unclear whether it is her decapitated head or her gaping mouth, typical of the Gorgon’s iconography, that evokes the act of castration, the figure of Medusa came to stand in Freudian thought as the female, castrated genital region.40 Moreover, her serpents function as fetishistic objects that displace men’s fear of castration by means of evoking men’s most prized possession.41 As the philosopher Hazel Barnes explains in The Meddling Gods, Medusa becomes the epitome of men’s fear of the castrating, petrifying female gaze, which can only be soothed through an objectifying and fetishistic male gaze.42 In Cixous’s text Medusa is retrieved and her laughter becomes a radical solution and an invitation to all women to laugh, for laughter, like the Bakhtinian carnivalesque, can debase oppressive dogmas of gender. In turn, Susan Suleiman claims that Cixous imagines a female spectator who finds the very notion of women’s castration laughable.43 Edelson’s Tricksters enact Cixous’s invitation to laugh at castration and to deconstruct myths that define women in relation to a lack. Her smirking grotesque goddesses are caught in the act of laughing at men’s anxieties and reclaim their pleasurable take on their own bodies.

Baubo and Sheela’s confrontational gazes and their active gestures acquire further relevance in this context as reclamations of the female gaze and agency. In her work on Baubo, Froma Zeitlin compares Baubo’s iconography and René Magritte’s Le Viol (Rape) (1934; Menil Collection, Houston) highlighting the conflation of head and genitals present in both images.44 The striking difference between Le Viol and Baubo, however, is that Magritte’s Le Viol has no access to the gaze nor to speech because her eyes and mouth have been replaced with her genitals. Instead, Baubo, like Sheela, is actively looking at the viewer and smiling. Edelson’s goddesses therefore oppose a female confrontational gaze that disallows the fetishistic consumption of their bodies and revindicates women’s control over themselves.

Through her recourse to the grotesque female body, Edelson further reinforced this comic defiance of the mastering sexualising gaze. Mary Russo discussed this use of the carnival grotesque body as a site of feminist possibilities to suggest alternative versions of femininity.45 Russo traced a genealogy of female grotesques that begins with the crone and terminates with the female patients suffering from ‘hysteria’ in the care of Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, who pathologically enacted society’s repression of the carnival spirit and the grotesque.46 Reading Bakhtin through a feminist lens, Russo contended that after the Middle Ages the female grotesque was repressed because she was deemed uncontrollable, irrational and overly sexual and therefore threatened the social status quo. This resulted in the view of the grotesque as ugly and repulsive.47 For Russo, a feminist return towards the grotesque could enact an insurgency against normative notions of femininity by comically unmasking the oppressiveness of the expectations placed on women’s objectified bodies.48 The grotesque bodies of Baubo and Sheela dwell in physical pleasures and deny the standards of beauty imposed onto the female body with a laugh that radically unsettles the phallocentric mastery over women’s bodies.

In her representation of Baubo, Edelson also invokes a story of female solidarity and of women coming together in laughter. Shirley Ardener suggests that Baubo’s exhibitionism was aimed at mocking the defilers of Persephone and Demeter in a show of solidarity for the injustices suffered by mother and daughter and that, in turn, this defiant rejection of male authority provoked the goddess’ burst of laughter.49 Baubo’s anasyrma and Demeter’s laughter were re-enacted every year during the Thesmophoria, a festival where women came together in Athens for three days to celebrate Demeter’s cult.50 On the second day women partaking in the festival honoured Demeter’s loss by engaging in sexually obscene gestures or jokes. Likewise, the Trickster Series enacts a humorous resistance to phallocentric constructs that perpetrate women’s oppression in a show of solidarity with other women. The implication of this parodic and comic gesture lies in the response of communal hilarity that it demands of its female public and in the strengthening of interpersonal relations – the belonging to a group of people who get the joke. Edelson’s images are a product of this premise of the unifying nature of laughter in a demonstration of female solidarity: the carnivalesque laughter that Edelson evokes affirms women’s sexual pleasure, exposes what is frightening about the female sex and equally encourages all women to embrace the same. In her writings on Nancy Spero, Jo Anna Isaak commented that Spero’s works speak to the fact that women have always been prone to laughter and have a particular stake in its political potential.51 However, prior to Spero’s own works on the Sheela, Edelson’s Trickster Series was already enacting women’s claim to laughter and encouraging its audience to share in its liberating potential.

In appropriating the myths of Baubo and Sheela and exploiting their potential for a feminist critique, Edelson’s historical mode of analysis traces a genealogy of women’s laughter and excavates stories of laughing mothers and daughters to reinscribe them in the agenda of the women’s liberation movement. This act of travelling into the past to retrieve a lost history of female solidarity and defiant pleasure gives Edelson’s images a timeless quality. The title of one of Edelson’s essays, ‘Success has 1,000 mothers’, is similarly an appeal to the shared histories of women coming together across the centuries. Within this context, Edelson’s retrieval of ancient myths and goddesses and their reimagination through a comic and parodic lexicon of the grotesque is a politically charged invitation to share in our ancient mothers’ laughter.

A public reappraisal

The appeal to carnivalesque laughter as a model for feminist critique formed the premise of the 1994 exhibition Bad Girls held at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, curated by Marcia Tucker.52 Permeating Tucker’s exhibition was the claim that humour distinguished a younger generation of women artists – the ‘bad girls’ – from the women artists of the 1960s and 1970s whose rage, Tucker seemed to suggest, prevented them from exploring the emancipatory potential of laughter.53 Unsurprisingly, therefore, many feminist works from the early 1970s were excluded, including Edelson’s goddesses despite their anticipation of the exhibition’s use of the carnivalesque. Although Bad Girls is only one example, its omission of works of art from this period nevertheless highlighted a bias in feminist scholarship, in which humour and parody are not considered to belong to the works of second-wave women artists.

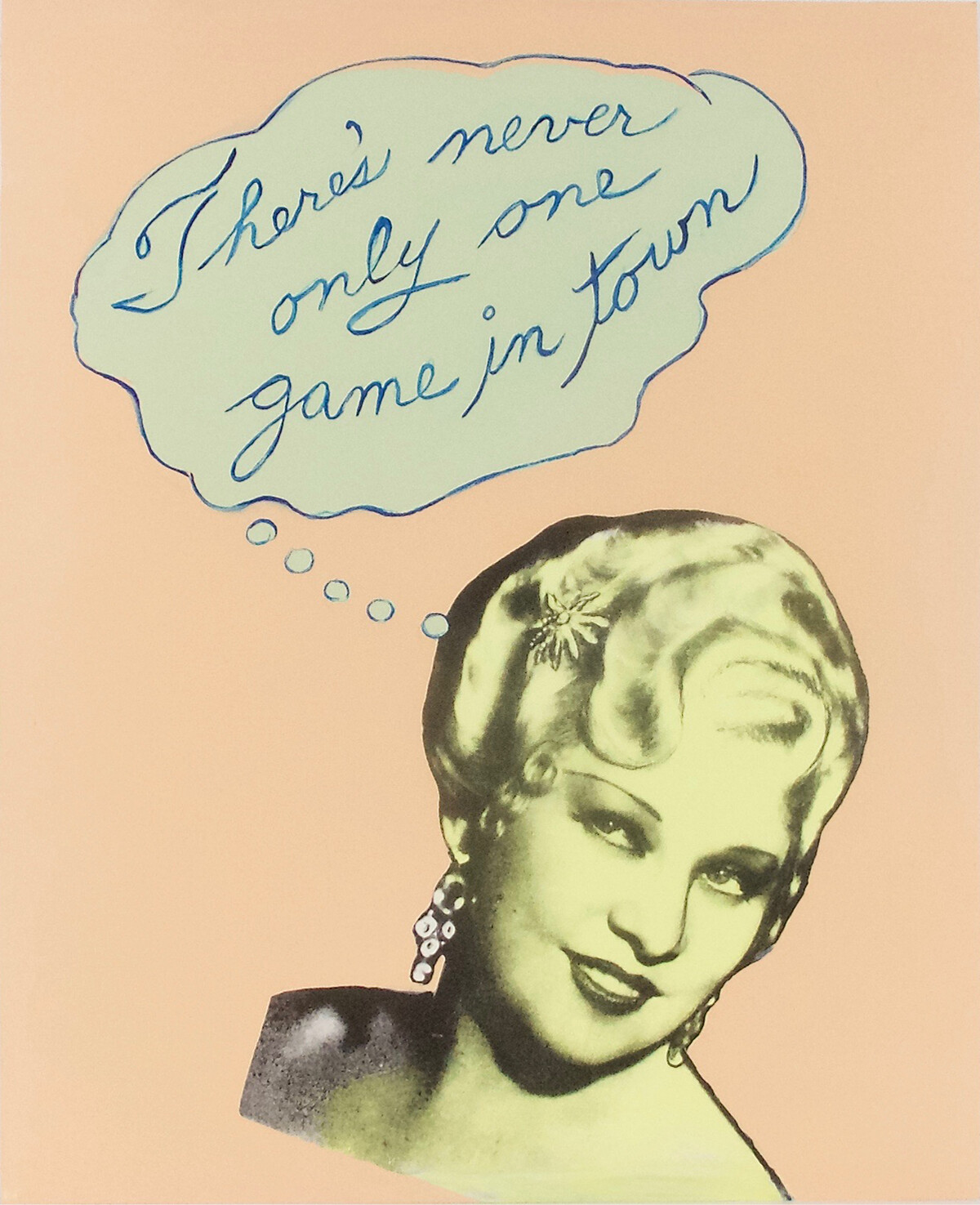

In her exhibition history, Edelson’s comic sensibility is mentioned solely in connection to her posters and works from the 1990s, but rarely in relation to her goddess imagery. The goddess remained prevalent in Edelson’s art throughout the 1960s, 1970s and the early 1980s. In conjunction with these works, Edelson also articulated her parodic interrogations of women’s representation through her posters and her Shooter Series. In Shooter Series, Edelson, inspired by E. Ann Kaplan’s Women in Film Noir (1978), collaged together images of Hollywood actresses holding guns as a way to reclaim women’s agency in films. These later works, together with her posters, have been exhibited extensively, particularly in feminist group shows, and have been discussed in relation to the artist’s use of humour. For instance, a number of posters for A.I.R were featured in Cornelia Butler’s travelling exhibition WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, which was first staged at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 2007.54 In 2015 the exhibition Mary Beth Edelson, Feminist Humour as Political Device, held at the Bernstein Gallery, Princeton University, promised to be an auspicious retrospective on Edelson’s investment in humour, but only displayed a small body of Edelson’s Hollywood collages, such as There Is Never Only One Game in Town FIG. 16. Although giving a new visibility to the work of Edelson, the omission of her goddesses from these exhibitions has heightened the divide between the critical reception of them and her other works. Moreover, it has reinforced the academic and curatorial bias that it is only through the denial of now-outdated belief systems that certain second-wave feminist artists can be included in the history of feminist art.

Only in the past five years has Edelson’s goddess imagery received more critical attention. In 2017, a solo exhibition at David Lewis Gallery, New York FIG. 17, The Devil Giving Birth to the Patriarchy, showed the Trickster Series alongside Edelson’s sculpture Kali Bobbit (1994), in which a mannequin, replete with dangling knives, revives André Masson’s Surrealist photographs with a feminist twist. In The Pleasure Principle, held in 2019 at Maccarone Gallery, Los Angeles, Edelson’s Trickster Series was exhibited side by side with works by Annie Sprinkle (b.1954) to trace a genealogy of provocative women’s art. Albeit a long time coming, these exhibitions aim to reframe the discussion of Edelson’s goddess images and represent an important step towards the reappraisal of feminist spiritualism in women’s art. More recently, the Feminist Institute, New York, partnered with Google Arts and Culture to digitalise the artist’s archives, affording unprecedented access to her work and offering renewed attention to her interest in the goddess.

Without suggesting an overdetermination of Edelson’s practice within goddess trends, this article is a similar attempt to reframe the discussion of Edelson’s goddess imagery by foregrounding a spiritualism alive with irony, playfulness, deconstructive critiques and parody. In the conclusion to Female Grotesques, Russo returned to Bakhtin’s remarks on the grotesque hags to underscore the radical potential of women’s laughter: ‘I see us viewed from ourselves and by others in ways that are continuously shifting the terms of viewing, so that looking at us, there will be a new question, the question that never occurred to Bakhtin in front of the Kerch terracotta: why are those hags laughing?’.55 Edelson’s Trickster Series prompts such a question. She accepted Cixous’s and Russo’s invitations to explore the radical potential of laughter and retrieved old laughter from other times – of Demeter and Baubo, of the women celebrating the Thesmophoria, as well as the carnivalesque laughter of the Middle Ages – to lay a claim to its liberating potential for women. Through a historical mode of analysis, Edelson’s goddess works offer at once an alternative, celebrative vocabulary that speaks of women’s pleasure and an engaged critique of logocentrism. Edelson’s art proposes a confrontation with history and myth and exemplifies the notion of a multiplicitous feminism open to parody as well as to lyricism and celebration, attesting to a feminist spirituality that is as politically enraged as it is witty and jocular.