Drawing out: speculative seriality in Richard Tuttle’s ‘Looking for the Map’

by Laura Lake Smith • June 2023. In collaboration with Drawing Room, London • Journal article

In progress

‘I put this enormous pressure on what drawing is, but I know it’s not the conventional way of thinking about drawing. Everything in life is drawing’.1

In early 2014 Richard Tuttle (b.1941) presented new work in an exhibition titled Looking for the Map at Pace Gallery, New York FIG. 1 FIG. 2. Billed as ‘drawings and studies’ that Tuttle had created for his upcoming project for the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, London, later that year, this exhibition – the press release noted – would display twenty new works in anticipation of Tuttle’s largest project to date. By conventional standards, then, it was expected that the exhibition would showcase early plans for the large-scale piece, but neither the work nor the accompanying labels made explicit reference to preliminary plans for what would eventually be a vast textile installation in the Turbine Hall. Instead, the exhibition presented twenty delicate, relatively modestly scaled and highly abstract works, comprising malleable and quotidian materials, such as wire, fabric, cotton and thread.

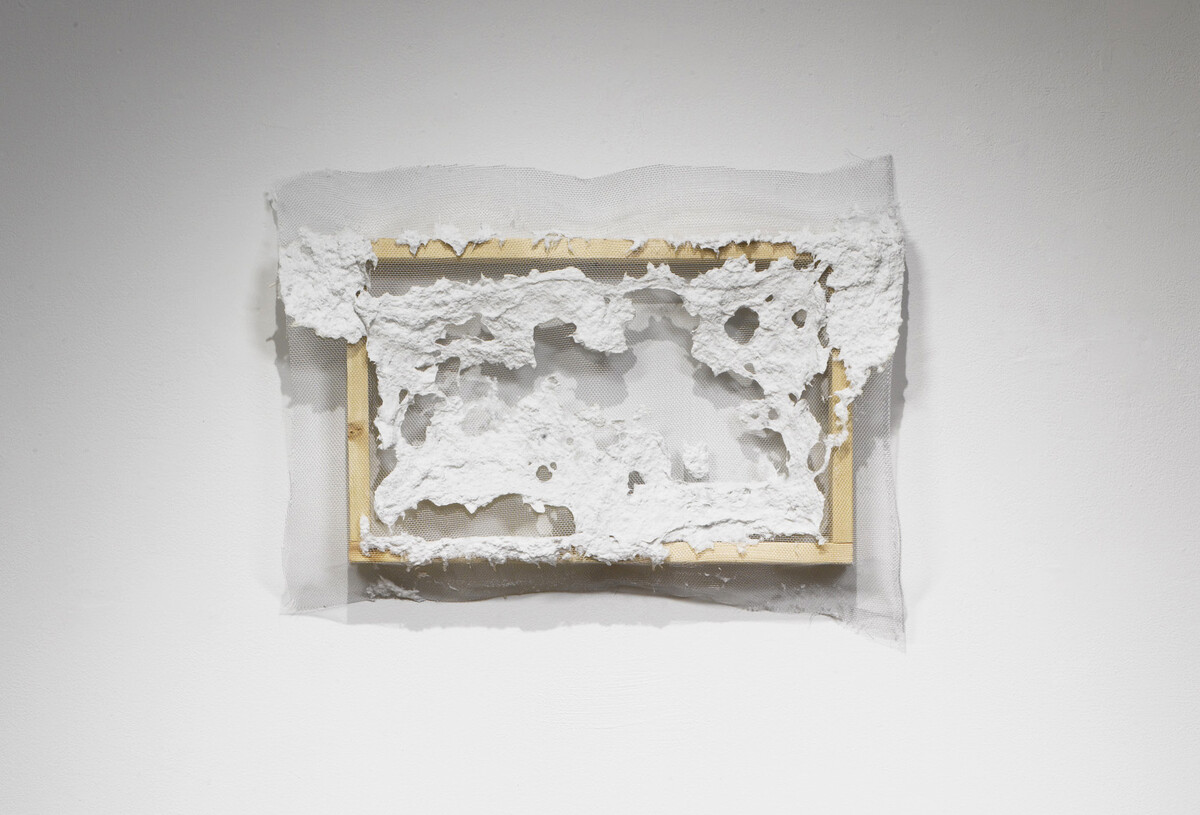

In fact, the exhibition included two disparate and distinct series: Looking for the Map 1–11 (2013–14) and PlusMinus 1–9 (2013–14). The works in the Looking for the Map series consist of different configurations of fabric, chicken wire, wood and pins, among other materials, and range in size from approximately half a metre to 2.5 metres in height. Some works are wall-bound, whereas other, larger makeshift pieces are sustained simply by being leaned against the walls FIG. 3. PlusMinus consists of small, wall-mounted works, comprising different configurations of cotton pulp affixed to wire mesh in a wooden framework. As this cursory survey of the work evinces, Tuttle’s forms are palpably mutable and unresolved, suggesting a sense of uncertainty, if not incoherence. This is made all the more evident by the manifestation of the drawings in series, which, when viewed in numerical order, create wandering lines that elicit confusion and irresolution. Although a certain degree of in-progress work would have suited the exhibition’s premise for something larger, Looking for the Map seemed to present an altogether different inflection of work in progress.

Drawing has long been seen as processual in nature and, whether deployed as a tool for detailed planning or an expression of thought, the medium is closely associated with temporality. Seen in this light, Tuttle’s serial drawings, rife with a sense of flux, appear to revel in the mutability of time. This article will consider the provisionality and irresolution of the serial drawings in Tuttle’s 2014 exhibition as ploys to reconfigure and expand the existing concepts of drawing. Tuttle is adept at deploying unorthodox materials in transitional states, and his method of drawing can be seen as a way of drawing by other means. The very activity is just as important as the works it produces, which are made in a curiously meandering, diverse and unresolved seriality. As a result, the act of drawing for Tuttle should be seen as a way of speculatively ‘drawing out’ – an ongoing means of thinking, searching and questioning.

Drawing in-between

Tuttle has a rich history of drawing by other means. Often associated with the movements of Post-minimalism and Process art that emerged in the mid-1960s, Tuttle’s work makes use of commonplace materials, such as domestic fabric, rope and wire, as well as the more traditional pencil – all of which highlight facticity, process and temporality. This is especially evident in his drawings that reconceptualise the fundamental components of line and plane or the relationships between figure and ground. These include Wire Pieces (1972), which are drawn directly onto the wall using pencil and lines of florist wires, and Ten Kinds of Memory and Memory Itself (1973), a drawing made with multiple strings, placed in various configurations on the floor, necessitating constant movement on the part of the viewer to take in the entire work. In much of the existing literature on Tuttle’s œuvre, his work is regularly discussed as being in flux or a temporary state.2 For example, the art critic and art historian Robert Pincus-Witten described Post-minimalist art as having an ‘emphasis on the process of making, a process so emphatic as to be seen as the primary content of the work itself’.3 Process as content, medium as meaningful: these are central tenets for a generation of artists who emerged in the wake of the modalities of both the highly personalised procedures of Abstract Expressionism and the severe, object-bound approaches of Minimalism.

Tuttle’s reimagining of drawing was recognised early on alongside a broader re-evaluation of the medium in the post-war era. By the mid-1970s Tuttle’s use of everyday materials had found kinship with the Italian movement of Arte Povera, the artistic explorations of which likewise engendered a new vernacular of drawing with unconventional materials and methods. In 1976 the Italian gallerist Ugo Ferranti sent Tuttle a request to show some ‘new drawings’ in his Rome gallery.4 Tuttle agreed and the following year he exhibited a series titled Scheggia (Splinter; 1977). These relatively diminutive abstract drawings, measuring approximately 4 by 8 by 1.5 centimetres, are made of gouache and acrylic chalk on thick pieces of roughly textured cardboard. This combination of materials and support locates these drawings in an ‘in-between’ place, fluctuating and splintering forms in the second and third dimensions. They read as both sculptural reliefs with painterly elements and drawings made of colourful incisions on a traditional support. Indeed, then and now, drawing for Tuttle defies categorisation – it is always unstable in its identity and seemingly toggling between the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional.

In 1976 one of the drawings from Wire Pieces, which were well known at the time for their untraditional transitional qualities, was included in the exhibition Drawing Now: 1955–1975 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). In the catalogue, the curator Bernice Rose assessed a new frontier of contemporary drawing in which Tuttle’s practice participates: ‘during the past twenty years a number of artists have, and with increasing intensity since the middle sixties, seriously investigated the nature of drawing’.5 As Rose noted, contemporary drawing was expanding in the hands of this new wave of artists – no longer just preparations for a final product, it was becoming fundamental to explorations of form, traces of process, marks of time and acts of contemplation. Rose’s essay is equally important for the lineage it presents of drawing since the Renaissance, reminding us that for this period of Western art history, drawing was largely subsidiary to painting, sculpture and architecture; throughout and prior to the Renaissance, it was more entangled with conceptual modes of speculation and ideation, as well as with the matters and processes of reality. By the 1970s contemporary drawing was restoring much of the latter ideas to the forefront of the medium.

It is unsurprising, then, that drawing for Tuttle at this time was radical in its materiality and technique, as well as its capacity for investigating the conceptual and speculative. For Tuttle, drawing is a practice that is entangled with the matters of life. In 1979 the artist stated that ‘the actual physical making of a drawing is very similar to comprehension’.6 Similarly, Susan Harris sees Tuttle’s drawing practice as ‘enmeshed with his processing of experiences, ideas and perceptions’, suggesting a sense of ‘philosophical freedom’, and Jennifer Gross contends that Tuttle’s drawings are ‘a process of three-dimensional inquiry’.7 Indeed, Tuttle sees his art as being concerned with a certain metaphorical ‘depth’ about ‘the world’s complexity’: ‘artwork has to work with a depth [...] about the depth that we operate in’.8 Such an interest becomes all the more salient when one considers that Tuttle’s shifting and liminal drawings are made in what can be termed a ‘speculative seriality’.

Seriality

Since the beginning of his career in the 1960s, Tuttle has worked almost entirely and deliberately in what the present author has contended elsewhere is a paradoxical and speculative seriality.9 Although the term ‘series’ has been used to describe a number of Tuttle’s projects, including by the artist himself, there has been a resistance to labelling the artist’s overall working method as ‘serial’, perhaps because his seriality confounds the conventional definition, which is associated with sameness or progression. Although Tuttle’s series may, at times, employ identical materials, similar constructions and chronological ordering, they ultimately do not follow discernible patterns. Instead, they appear unfinished and wilfully unresolved, with each work representing a different moment in some provisional unfolding. Moreover, the last work of any of Tuttle’s chronologically produced series – conventionally a moment of resolution – appears only as an arbitrary end, an abrupt break in a trajectory that could have continued, if only it was allowed to do so. Thus, in encountering Tuttle’s seriality, one may feel that they have been drawn into a logic that is obscure, uncertain and unfinished. When this searching incoherence is considered alongside the provisional constitution of his abstract drawings using dispensable, quotidian materials, Tuttle’s serial art can be understood in reference to the processual nature of life. His speculative seriality becomes a doubly articulated method of ‘drawing out’: at once a formal means for imaging transience and flux and a philosophical means of investigating the ever-changing conditions, observations and thoughts of human existence.

Although the subjects of his philosophical inquiries vary throughout his œuvre, Tuttle’s seriality often questions and subverts the conceptual underpinnings of conventional seriality and its associated systems, models and methods, taking aim at the predictability, coherence and resolution that such modes typically proffer. This has been particularly productive when explored in a dedicated solo exhibition format: ‘I’m of a generation where you do a show to find out [...] as a kind of experiment. I’m asking, “can we do this?”’.10 This framework of experiment is especially significant when assessing Looking for the Map, considering that its contents were positioned as ‘drawings and studies’ for a future large-scale project. As with other serial endeavours in the artist’s œuvre, Looking for the Map 1–11 and PlusMinus 1–9 aim to draw out different propositions for drawings and studies. But, as this article will also contend, such a ‘drawing out’ in Tuttle’s exhibition has philosophical import beyond the methods and ambitions of drawing throughout history.

Speculating

It is worth noting that the titles of both series reference more conventional strategies for drawings and studies: for example, the use of ‘map’ and more evocatively, ‘plus’ and ‘minus’, which conjure varying notions of grids, such as the coordinates typically associated with latitude and longitude. Even so, these references are qualified by some means of uncertainty and doubt. The phrase ‘looking for’ signifies the act of searching and the feeling of confusion that can accompany it, whereas PlusMinus suggests an in-process flow as opposed to particular points or specific conjunctions. Moreover, the form, materials and presentation of PlusMinus 1–9 refer to maps only in an abstract manner. As with conventional geographic mapping, Tuttle adds colours to cotton pulp that appear to have specific associations with the earth: blue, yellow, oranges and white. However, because of their high degree of abstraction, the drawings give no indication of a fixed or precisely plotted location. Much as the title itself suggests, the constituent elements of these drawings seem to undulate with a strangeness that defies categorisation.

For all its deviations, the PlusMinus series does also evoke conventional means of drawing. Its variously configured applications of cotton pulp connote drawing’s traditional and typically inconspicuous, support: paper. Moreover, the pulp is embedded in wire mesh grids, which is redolent of another age-old tool: the grid used for academic drawing. Codified by the Renaissance humanist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) in his treatise On Painting (1435), the grid (or ‘the veil’) became the method par excellence for capturing and fixing the view of the artist.11 While the grid is an integral part of the linear perspectival system but ultimately invisible in the finished work, for Alberti, it was also considered a crucial disciplinary tactic that aided in reifying a certain way of seeing, presenting ‘the same surface unchanged’.12 However, the drawings in PlusMinus do not indicate fixity and they make the elements of paper and grid all the more conspicuous. In this way Tuttle’s deployment of these well-known, traditional methods can be seen as generating possibilities more associated with the discursive processes of thinking (and rethinking) and of making (and remaking) maps and studies for what might lie ahead, rather than charting what is already known.

Indeed, in spite of their orthodox attachment to the wall by small, wooden frames, the paper and grids that comprise the works in PlusMinus suggest movement and mutability. In PlusMinus 9 FIG. 4, for example, the white cotton pulp appears to be in the process of formation, as though an image is struggling to cohere or perhaps, more fundamentally, struggling to remain fixed to the gridded wire mesh. The mesh is pliable, almost flimsy, seemingly contingent to being draped across the frame. The frame is, of course, also a familiar concept in art history: it is an entity that can be either invisible or visible, operating as a conceptual framework or as a physical object that delimits something from the rest of the space that it occupies. But in PlusMinus 9, as with the entire series, the frame is made both to contain its contents and be noticed, but also to have its boundaries overrun. Hence, rather than the enclosing or even foreclosing potential of what might emerge, Tuttle’s seriality in PlusMinus encourages the ongoing and speculative shifts in thinking about a subject as well as how one might navigate the way forwards. And, as evidenced by the seemingly haphazard applications of the pulp throughout the series, it perhaps encourages the messiness of such endeavours as well.13

However, if Tuttle’s PlusMinus series enacts critical interventions into the long histories of drawing, the same can be said for another history that is also interested in notions of fixity and, moreover, is closer to hand for Tuttle and his contemporaries: that of modernism. For example, the recurrent and paradoxical use of the grid in PlusMinus overlaps with the concept of ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ found in the paintings of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). Beginning in 1915 with such paintings as Piers and Oceans (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo), Mondrian embarked on a quest to reduce nature to horizontals and verticals. While it is generally agreed that his so-called ‘plus and minus phase’ ended c.1917, the fascination with the grids inherent in these paintings continued, in various manifestations, for the rest of his career. Grids became an essentialised and standardised means to express what Mondrian believed to be the purity and harmony underlying reality, a determinate universal equilibrium, which was perhaps best expressed in his 1920 essay ‘Neo-Plasticism: the general principle of plastic equivalence’.14 For Mondrian, the immutability of the grid provided a kind of map for how one could understand the absolute nature of things and navigate life accordingly.

Tuttle is hardly the first artist of the post-war era to reconsider Mondrian’s ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ paintings and their attendant ambitions.15 Indeed, Tuttle is no modernist, once noting: ‘I’ve been against modernism since I began’.16 And yet, Tuttle, like Mondrian, is an abstract experimentalist, interested in exploring the possibilities of drawing with grids and imaging something fundamental about the nature of reality. But this is where the two artists diverge. Of course, if Tuttle’s PlusMinus drawings can be said to evince any underlying constant of reality, it is that nothing is immutable and determinate – a notion that is subtly underscored by the shadows that constitute each of these serial drawings. Illuminated by a strong light source, the pieces of pulp and wire mesh cast spectral extensions of their tangible forms both in and beyond the wooden frames. These mutable shadowy projections conjure associations of the unknown and deny any guarantee of certainty or fixity. In this way, PlusMinus signals that no single attempt at mapping, gridding or drawing can fully encapsulate the infinite variety and complexity in drawing out the possibilities in thinking, making or even in navigating life more broadly.

Searching

As an exhibition, Looking for the Map provided no clear set-up as to how to read the relationship between the two disparate series. However, given that Looking for the Map 1–11 lends the exhibition its title, it seemed to have a greater gravitas, a sense that is further encouraged by the series’ larger and more sculptural drawings, which appear ever so slightly heavier in their constitution. This is also due, in part, to the kinds of materials employed, which include large segments of chicken wire, swathes of fabric and wooden slats and structures. Moreover, because this series of drawings comprise both smaller, wall-bound pieces and larger works dependent on both ground and wall, Looking for the Map 1–11 appeared, at first glance, as more dissonant and more meandering in its logic. If the PlusMinus series can be construed as a set of more focused meditations on the mutability of thought, plans and life, then, in Looking for the Map one is certainly set adrift and left to wander.

From certain angles, some of Tuttle’s drawings in Looking for the Map seem to be in motion. For example, one resembles a small, padded sled, sweeping diagonally across the wall FIG. 5. Close by, another suggests a wooden ladder that has been hastily padded, draped and tufted in fabric – manifesting as an impromptu vertical cushion or mattress, or an abstract body in voluminous garments. In another FIG. 6, a column of red fabric leaning against a sturdy wooden platform intimates a post, buoy or beacon. Despite materials that hint at wrangling or securing, such as chicken wire, the red fabric is uncontainable, seeping out of its confinement from below as well as above.

Indeed, as much as he uses wires, pins, clips and wooden slats, in Looking for the Map Tuttle deploys coloured fabric to generate mutable forms.17 Looking for the Map 10 FIG. 7 comprises a circular form that is tightly wrapped in pink, blue and navy fabrics. However, a darker piece of fabric disrupts this repetitive circularity, emerging through the central hole and spilling down. This also draws attention to the tree branches suspended from the bottom centre of the circle, which are suggestive of forking paths in a road. Looking for the Map 8 FIG. 8 is composed of a heavy wooden palette-like structure on the floor, minimally draped with an energetic line of blue and green fabric. A lightweight wooden stick connects the palette to the wall, where layers of opaque fabrics in black, blue and pink, and a surplus of delicate blue netting, are draped over an underlying rectangular armature made out of wire. Like some of the other larger floor works in this series, Looking for the Map 8 is suggestive of makeshift craft; it resembles a raft with fluid, billowing sails, conjuring notions of voyages and expeditions.

When taken together, the drawings in Looking for the Map can be seen as abstract manifestations of conveyancing tools, waypoints or signposts. They represent either means or moments of liminality, emphasised all the more by their provisional constitutions and the notable variations from one drawing to the next. It could be argued, then, that the meditations of mutability and uncertainty explored in the PlusMinus series are drawn out in more exaggerated conditions in Looking for the Map and proffered as though they were contingent, speculative practices in the more general aim of ‘looking for the map’.

There is, however, a palpable confusion and frustration in the experience of ‘looking for the map’. In Looking for the Map 4 FIG. 9 green and red hues read as soft renderings of stark, illuminating waypoints, such as traffic lights or emergency signs. However, because these signalling colours are all enmeshed into one sign, the sense of direction – of whether and when one should go or stop – is perpetually unclear. More so than in the PlusMinus series, Tuttle’s Looking for the Map drawings disguise neither the graft nor the tenuousness of their making. Rather, they appear to wilfully image the questions and ambiguities that the act of searching entails.

Although they share an insubstantial quality with the works in PlusMinus, there is an added softness in the Looking for the Map drawings. From girding and padding to wrapping and draping, the coloured fabrics are evocative of the corporeal. Although Tuttle’s sculptural drawings are not precisely images of us, they nevertheless seem to convey something about our own temporal and shifting conditions. Madeleine Grynsztejn contended that the use of commonplace materials and transitional intimations in Tuttle’s larger works, such as his Floor Drawings (1987–89), ultimately suggest a correspondence with the viewer, as these differing conditions in the work are not unlike our own.18 In a 1975 exhibition essay Marcia Tucker, then the curator of the Whitney Museum, New York, stated that there are moments in Tuttle’s highly abstract art that ‘when, in dialogue with it, we are able to recognize ourselves’.19 In the Looking for the Map series, we seem further implicated by the title; after all, ‘looking for the map’ is a broader, speculative practice that we draw out in our daily lives.

Beginnings and endings

The installation of Tuttle’s two series further drew out their provisionality and irresolution. It is notable that the individual drawings of PlusMinus and Looking for the Map were displayed throughout the gallery in an interwoven fashion, such that in moving through the space, visitors would encounter one work from PlusMinus, followed by one from Looking for the Map, and so on. It is a strategy that not only placed viewers in dialogue with the series, but also placed the two series in dialogue with each other. One could consider Looking for the Map as a problem or question posed, to which PlusMinus was a fleeting answer; or perhaps the other way around.

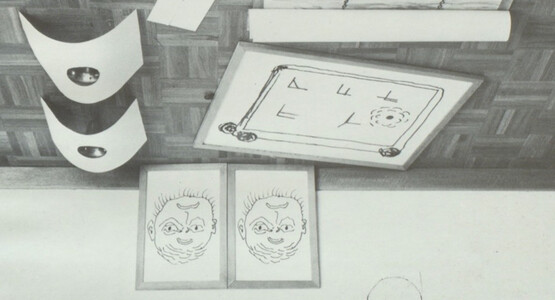

Such an ongoing endeavour was further emphasised by two pieces on the walls, which were ostensibly directional signage and unconnected to the drawings: ‘LOOKING FOR THE MAP – THE BEGINNING’ FIG. 10 and ‘LOOKING FOR THE MAP – THE ENDING’ FIG. 11. These texts were printed on the wall in a circular shape, each with a small object placed in the centre. ‘The beginning’ was a blue square of wood with holes cut out to make a grid, recalling the grids in the wire mesh of PlusMinus, whereas ‘the ending’ featured an object made of two plywood blocks, with one seeming to emerge from the other, not unlike the wooden structures in Looking for the Map. If this indeed was an ending, it hinted that something was still moving, still becoming other. As these works occupied opposing wall space at what was both the entrance and exit of the gallery, the points of beginnings and endings were elided, as though they indicated a temporal waypoint amid an ongoing journey.

As with the PlusMinus series, ‘the beginning’ is more suggestive of conventional mapping and gridding. In a sense perhaps it is where we all begin, with the hope that tools, such as plans, maps and studies, will lead us to successful and satisfying, if not absolute, resolutions. Indeed, processes of planning and finding the way forwards are full of incoherence, doubts and uncertainty, but, as Tuttle’s speculative seriality has drawn out, such endeavours – and here the conventional points of beginning and ending too – can become exploratory, generative and productively incessant, wherein one moment, idea or realisation is always giving way to another. In Tuttle’s ‘ending’, we begin to look for the map anew.

Coda: still questioning

‘Solutions are not always declarations or emphatic statements; a solution can be a question’.20

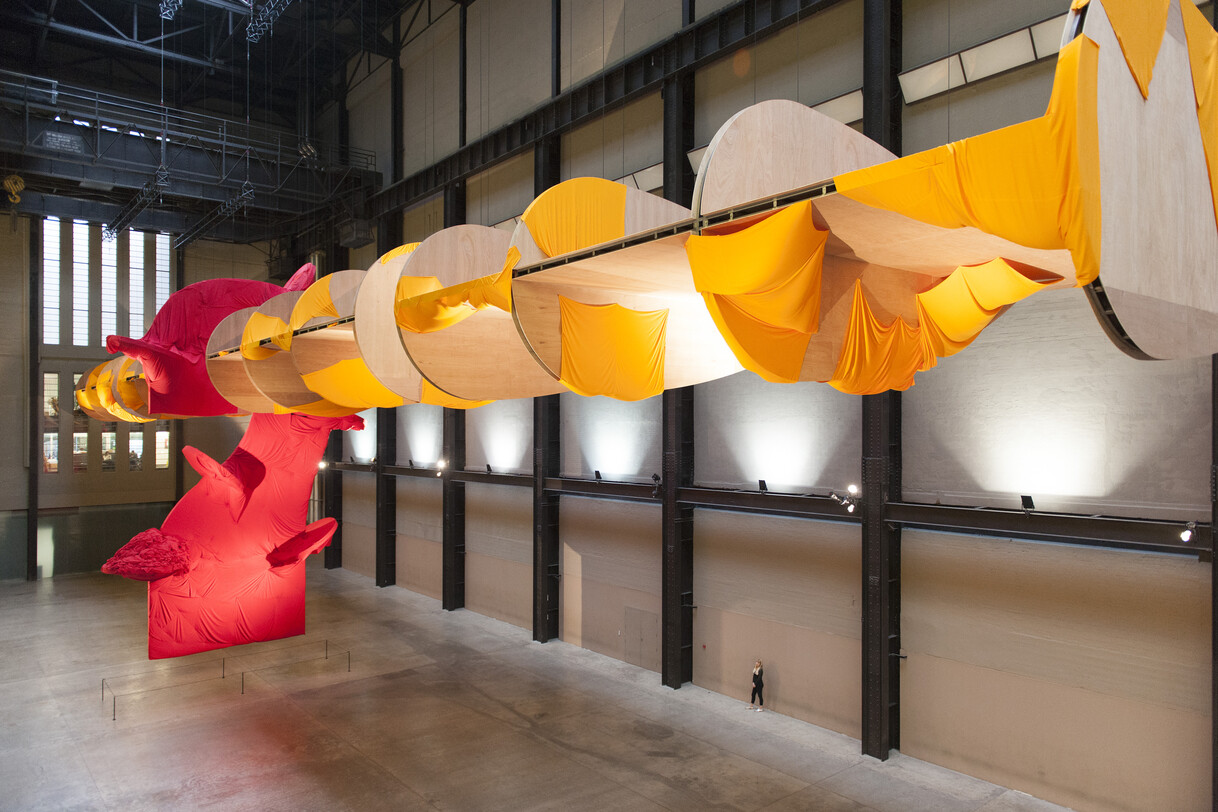

As an exhibition, Looking for the Map was never, as some believed, an attempt by Tuttle to obfuscate his designs for the Turbine Hall. Rather, Looking for the Map and its constitute components can be seen as earnest investigations of ideas and forms that would then find manifestation and amplification in Tuttle’s largest-ever work. In a Tate catalogue essay, Achim Borchardt-Hume wrote of the artist’s method in preparing for the project, saying that by producing ‘a whole new series of works’ in the Looking for the Map exhibition as studies for the final work, Tuttle ultimately underscored ‘that it is only experience – the experience of making and looking – that can provide guidance and that experience alone would dictate what questions can be answered’.21 If questions were answered about the way forwards, then the answers were drawn out in an emblem that is borne of and bound to speculation, uncertainty and provisionality. The central component of the massive construction, titled I Don’t Know. The Weave of Textile Language FIG. 12, was in fact an abstracted question mark.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the generosity of Richard Tuttle as well as the assistance of Pace Gallery. Research for this project was generously supported by a Luce/ACLS Dissertation Fellowship in American Art, the Willson Center for the Humanities at the University of Georgia and the University of Alabama in Huntsville. Thanks also to Isabelle Loring Wallace for her incisive thinking on this project as well as to those who responded to earlier versions of this article.