Cut-outs and ‘silent companions’: theatricality and satire in Lubaina Himid’s ‘A Fashionable Marriage’

by Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd • November 2019

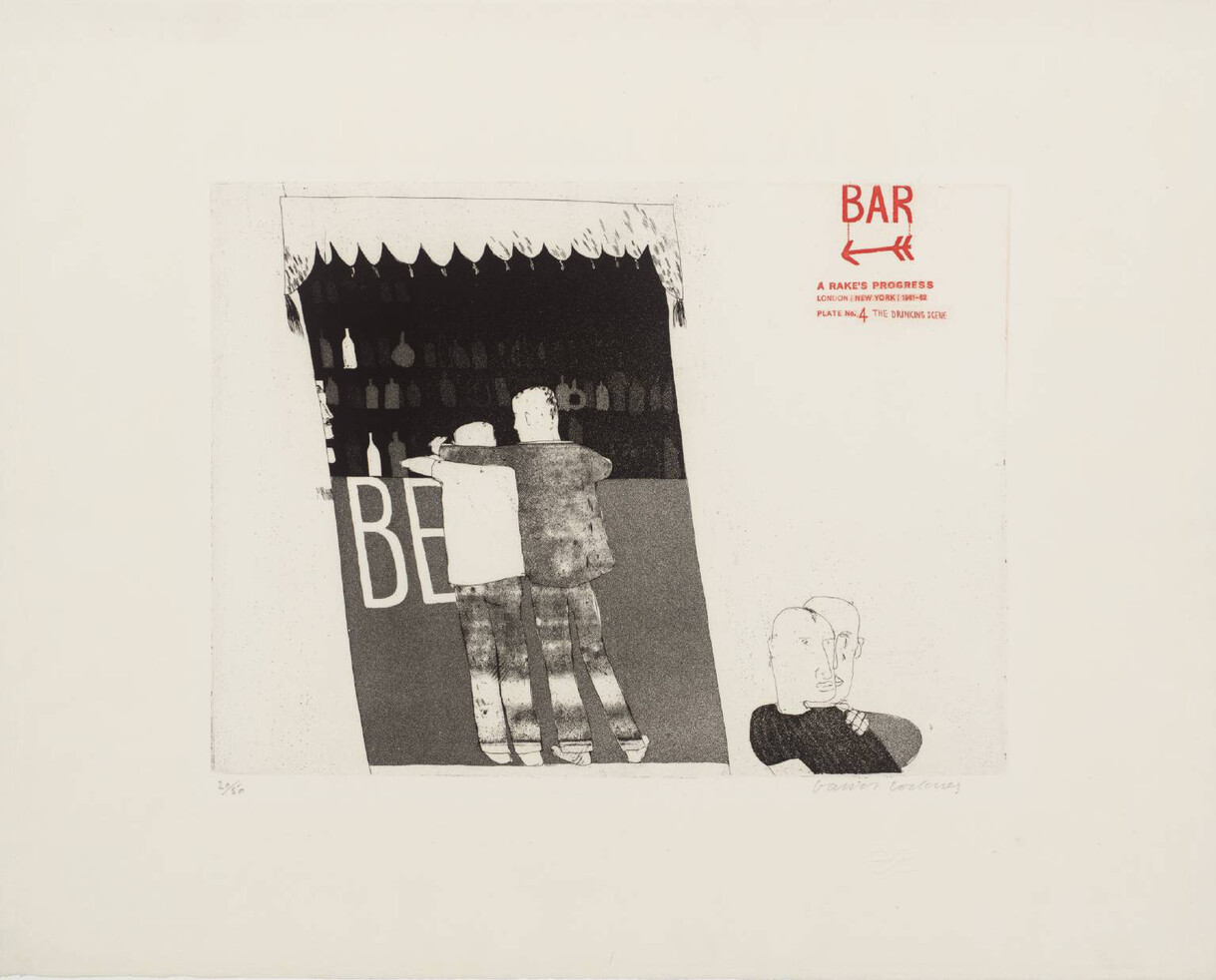

In the early 1970s, when she was working at the now-defunct New Artists Gallery in London, Lubaina Himid met David Hockney.1 This prompted Himid to begin an extensive study of Hockney’s Rake’s Progress print series (1960–61), at a time when Hockney was revisiting them while completing set designs for Igor Stravinsky’s opera The Rake’s Progress, to be presented at Glyndebourne, East Sussex in 1975. Quoting from William Hogarth’s eighteenth-century narrative series of the same name, Hockney’s series felt ‘very current’, to Himid, as it brought Hogarth back into the ‘thought-about, talked-about canon’.2 Some fifteen years later Himid completed her own Hogarthian appropriation. A Fashionable Marriage FIG. 1, titled after Hogarth’s Marriage A-la-Mode (c.1733–35; National Gallery, London),3 was an installation produced during what has been referred to as a ‘Black Arts Movement in Britain’.4 In line with the politics of this loosely, and sometimes controversially, defined movement,5 Himid’s Marriage critiqued conservative politics in the United States and United Kingdom in the 1980s as well as the exclusionary practices of the London art world.

Art-historical scholarship on Himid has tended to focus on her work in relation to feminist art, Black Atlantic-informed narratives and its engagement with Hogarth, but her recurrent use of the cut-out form in installations has not been fully explored.6 An examination of them summons other areas of scholarship that have been hinted at, but rarely mined substantially: Himid’s early grounding in set design at the Wimbledon School of Art; her stylistic engagement with Hockney’s work; and the influence of dummy boards or ‘silent companions’ – flat, often life-size painted wood figures, which originated in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century as decorations and advertisements.7

In its ambition to highlight, in a highly performative fashion, a Black British or Black European presence, past and present, A Fashionable Marriage was greatly influenced by its immediate context, namely 1980s art-making practices in the United Kingdom. This essay considers Himid’s development of the cut-out form, charting the formal and conceptual impact of her early studies in theatre design, and the influence of Hockney and Hogarth in the artist’s continuing engagement with theatrical devices.

A Black arts movement and history painting

The Black Arts Movement emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1980s, in a political context marked by a significant rise in racially motivated attacks against Afro-Caribbean and Asian populations.8 Racial tensions peaked intermittently with the arrival of Commonwealth citizens in England from the 1940s onwards, and by the early 1970s neo-fascist groups such as the National Front had become increasingly visible and vocal through street rallies and protests that attacked (particularly non-white) immigration to Britain, and clashed with anti-fascist protesters. Policing efforts aimed at restraining these groups culminated in a series of uprisings during the 1980s, the most serious of which occurred in areas – such as Brixton in London and Toxteth in Liverpool – with large ethnic minority communities. Institutional responses included the funding of anti-racist projects by the Greater London Council (GLC), the Labour-controlled administrative body for the capital until 1985; the development of Black British film workshops such as Sankofa and Black Audio Film Collective; and visual arts events organised by artists of African and Asian descent.9

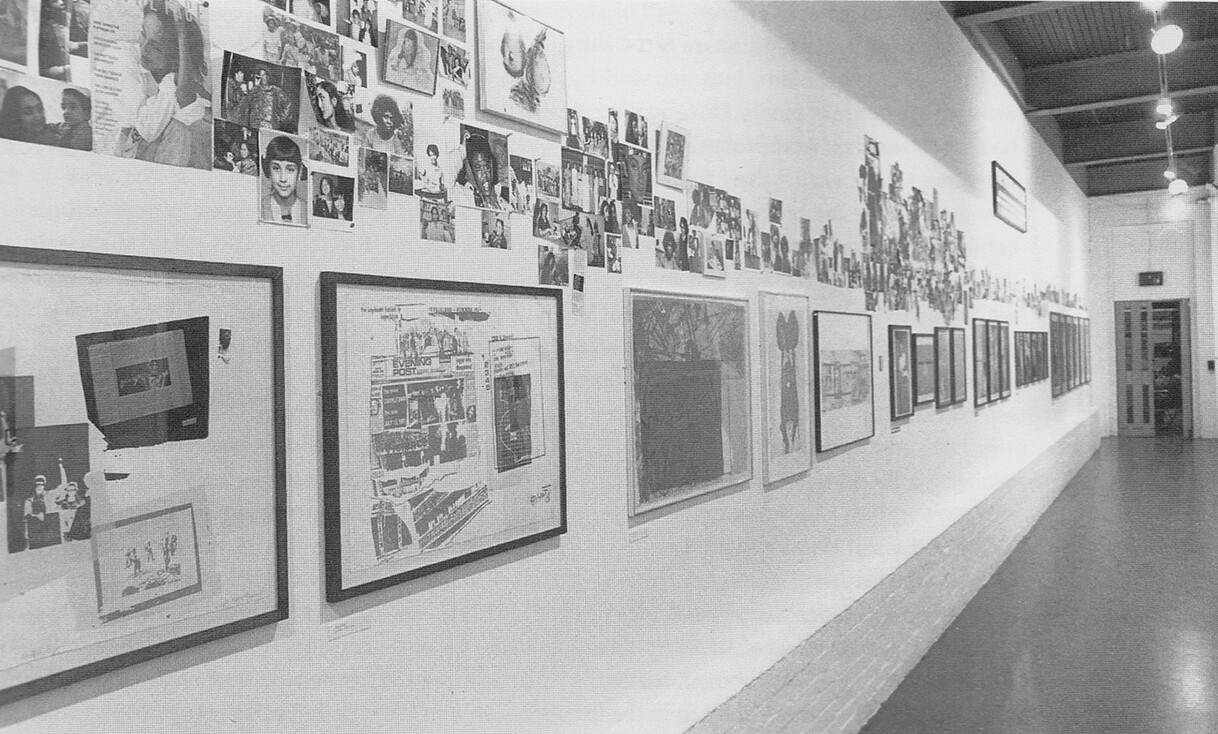

During this period Himid gained increasing attention for both her own work and for organising feminist-driven exhibitions, publications and other curatorial and administrative efforts that ensured the visibility of Black women artists.10 Three notable such exhibitions, all in London, were Five Black Women at The Africa Centre (1983); Black Woman Time Now, an arts festival held at the Battersea Arts Centre (1983–84); and The Thin Black Line, an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA; 1985) FIG. 2.11

The decade also saw a new academic interest in revisiting histories of migration.12 In art history this revisionist approach was beginning to bear fruit, with the publication in 1985 of texts such as Hogarth’s Blacks: Images of Blacks in Eighteenth Century English Art, David Dabydeen’s examination of figures of African descent in pictures by Hogarth and his contemporaries. These visual and literary texts provided evidence of a Black British presence: of servants and enslaved Africans that were key to establishing British wealth from the late sixteenth century onwards; and of Caribbean populations recruited to rebuild England after the Second World War. Himid and her peers associated with the movement sought to ensure that an enduring Black and British presence would not be forgotten.13

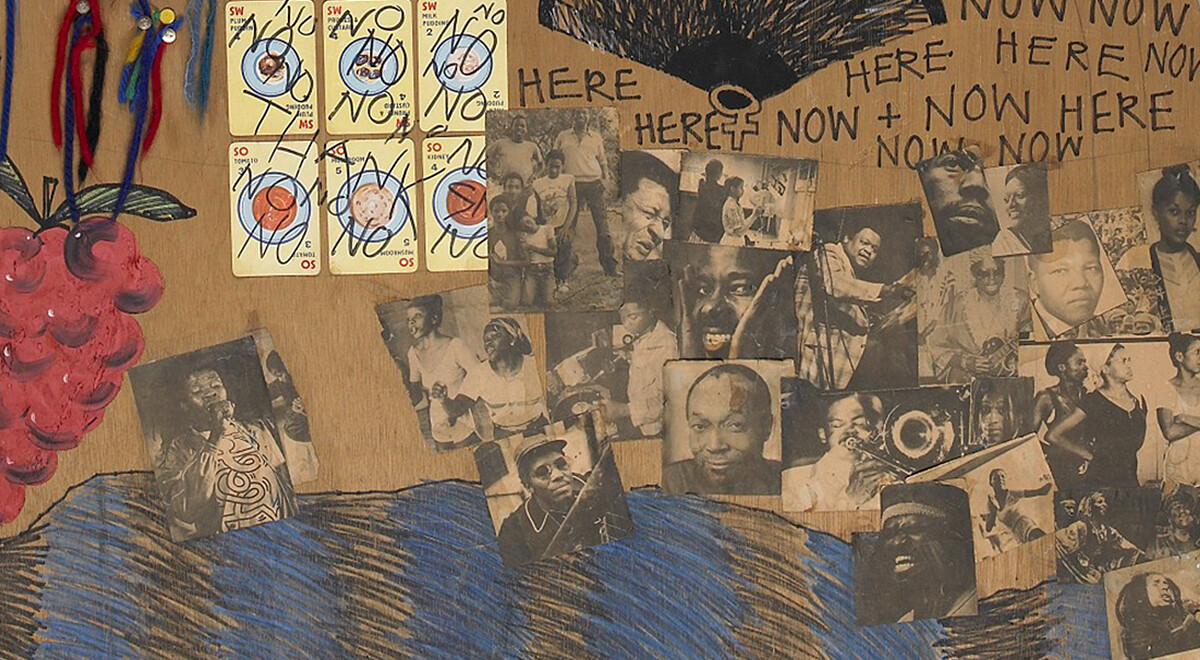

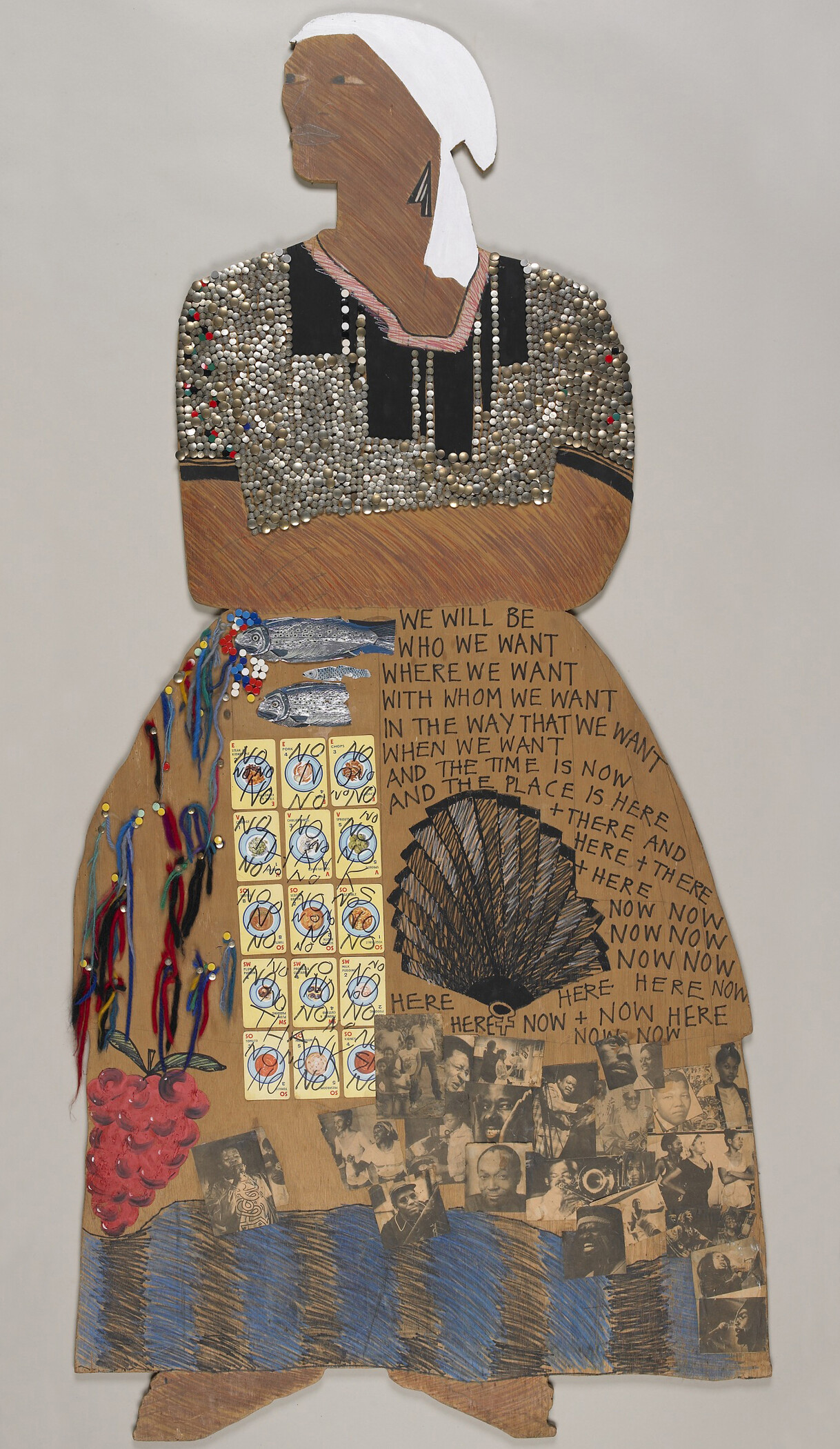

Himid’s early cut-out figure We Will Be FIG. 3, which was included in Black Woman Time Now, is collaged with a diasporic photomontage of Nelson Mandela, Bob Marley and other largely male symbols of cultural and political liberation. Characteristic of the aesthetics associated with the Black Arts Movement, the figure uses monumentality, expressive gesture and graffiti-like text to convey its direct and historically referential message. Griselda Pollock has discussed Himid’s works from this period in terms of a ‘reworked concept of history painting’, which has ‘consistently staged [. . .] problems of loss, mourning, absence’.14 Himid has always referred to her cut-outs as paintings, and the cut-out form may be viewed as a kind of animation, or activation, of figures less visible in European painting.

Himid’s series of eleven paintings titled Revenge (1991–92) engages closely with the genre of history painting, reconceiving the central role of Black women within official narratives of art and social history. One of the canvases in the series, Between the Two My Heart is Balanced FIG. 4, is based on Portsmouth dockyard by the French London-based artist James Tissot (1836–1902) FIG. 5. Tissot’s painting depicts a Highland soldier seated between two women – possibly potential romantic interests,15 or a woman and her sister as chaperone – in a boat sailing down the river Thames. Notably, the male figure is adorned in Highland Regiment uniform, with a redcoat (scarlet tunic), kilt and feathered bearskin, together indicating his military status, reflecting the romanticised and hypermasculine image of the Scottish soldier as fierce in combat.16

Himid’s canvas is much larger – closer to the scale of traditional history painting – and takes as its protagonists two women who are based on Himid and her partner at that time, the artist Maud Sulter.17 On the left, an Egyptianised Himid flings lengthy strips of rainbow-coloured paper overboard. Seen in profile with a forward-facing eye and a tall headress, the figure evokes the fourteenth-century BC portrait bust of Nefertiti in the Neues Museum, Berlin. Accompanied by an inscription, ‘Two women sit in a small boat tearing up navigation charts: how many died crossing the water?’, the work can be read as a statement on the Middle Passage.18 Himid notes that with Revenge, she was ‘trying to write myself, paint myself, and my compatriots, my fellow Black artists [. . .] into the history of British painting’.19 Here, Himid has transformed a scene of white male privilege, and specifically military status, into that of a Black female couple performing an empowering ritual of spiritual cleansing at sea. Additionally, the image also evinces a Black lesbian subjectivity that was rarely seen in Black Arts Movement practices in 1980s Britain.20 Himid’s engagement with art history served as a tactic that functioned in tandem with the emergent patterns of the Black Arts Movement in Britain and its periodic focus on African diasporic identity and issues of migration.

Hockney, Hogarth and the theatre

Himid’s work bears striking affinities with that of David Hockney in its use of broad sweeping brushstrokes, emphasis on the figure, commitment to art-historical research, explorations of LGBTQ sexuality, and its inclusion of graffiti-like text and other materials that speak to Pop-infused sensibilities. The two artists also share an interest in the theatre and theatrical, especially evident in their reimagining of series by Hogarth.

Hockney’s series of sixteen etchings for the Rake’s Progress is loosely based on the artist’s first visit to the United States in 1961 FIG. 6. The insertion of his personal narrative into Hogarth’s tale of moral decline gave Hockney a framework for exploring his identity as a young gay artist, while echoing Hogarth’s critique of absent morals and vanity-driven excess.

Hockney’s set designs FIG. 7 and costumes for Glyndebourne were also based on Hogarth’s compositions.21 Hockney’s sets FIG. 8 featured extensive cross-hatching and a limited palette, reflective of the inks available in eighteenth-century England, to evoke the multi-layered graphic style of Hogarth’s prints.22 Hockney ‘simply chose what would have been standard printing colours in the 18th century’, for which he purchased ‘good German inks; red, blue, green and black’.23

Both Hogarth and Hockney had strong links to the theatre. Hogarth was a friend of the actor David Garrick and the playwright and novelist Henry Fielding,24 and many of his works, such as the satirical print Masquerades and operas (1723–24), or the paintings Strolling actresses dressing in a barn (1738, destroyed 1847) and The Beggar’s Opera (1790; Tate, London) referenced, critiqued and celebrated these entertainments.25 Hockney’s affinity for dramatic narrative and performance is clear, from the incorporation of curtains in his work to his ongoing experimentation with illusion, perspective and spatial representation in paintings such as Play Within a Play (1963; private collection).

Himid’s work incorporates many of these devices, employing stage-like environments, playful and pointed experiments with scale and illusion that reflect her interest in theatre. She received a B.A. in Theatre Design from the Wimbledon School of Art, London, in 1976, where she designed productions such as Fishing by Paulette Randall, Sophocles’ Antigone and Pantomime by Derek Walcott.26 Such training is evident in her use of cut-outs, and in the stage-like presentation of her installations.

A fashionable marriage

Hogarth’s Marriage A-la-Mode (1743–45) chronicles the doomed arranged union of the bankrupted Lord Squanderfield’s son and the daughter of a wealthy merchant. The series engages with the pitfalls of seeking social elevation at moral cost, London as urban theatre and critiques of materialism and sexual boundlessness. Himid’s A Fashionable Marriage is a re-working of Hogarth’s ‘Scene Four’, The Toilette FIG. 9, in which the newly married countess hosts visitors at a morning levée, a French court practice of receiving company while preparing for the day. With her husband away, the Countess takes an audience in her bedroom as she converses with her lover Silvertongue, a lawyer.

Himid’s interpretation of the scene features ten cut-out characters comprised of paint on wood, with nails, newspaper and magazine clippings and other collaged elements. Each figure is slightly larger than life-size, and when properly installed the whole work measures approximately six metres across. The installation is divided into two sections: ‘The Art World’ FIG. 10, and ‘The Real World’. At the far left of ‘The Art World’ is a portly ‘art critic’, an interpretation of Hogarth’s plump castrato.27 He is seated in front of an ‘art collector/dealer’ (Hogarth’s flautist), who leans against the wall of the installation. Himid has mounted the collector on an unpainted, seven-foot-tall wooden plank that is plastered with spray-painted British pound signs and torn American dollar bills, chosen over sterling because ‘Real money is American money, international money’.28

To the right of the art critic is a male arts funder, who sits on a rudimentary fence, ‘unable to decide between the critic’s song and the fad of the day. Should he support the disabled, the Black, the women, or wait until someone else gives permission – the countess perhaps?’.29 His presence documents the instability of support (despite the GLC’s efforts) for artists considered ‘other’ in 1980s London.30 Next along are two embracing men with red lips, labelled as ‘The Angst/Complacent School of British Painting’. Himid has suggested that she was ‘thinking about Gilbert and George and [. . .] Stephen and Adrian Wisziewski’.31 The latter artists, part of the so-called New Glasgow Boys, were viewed, according to Himid, as ‘the saviours of painting’. Rejecting the minimalism and abstraction that were prevalent during this period, they produced works that incorporated narrative, social realism, history painting and the human figure. Yet they operated in a privileged realm of British art, populated by elite, and often dandified, white males, and benefited from an environment in which their work was ‘firmly placed in a private commercial dealer system’.32 These figures might be seen as part of a larger critique of gay white male privilege in the art world, another aspect, perhaps, to Himid’s engagement with Hockney.

The next character in Himid’s display, ‘Feminist Artist (Cult of the Individual)’, takes the form of a Dada-inspired tower of boxes FIG. 11 that displays two plates featuring stylised vaginal designs in an allusion to Judy Chicago’s installation The Dinner Party (1974–79).33 The figure is representative of the exclusionary practices of the feminist art movement in the United States: Chicago’s Dinner Party included thirty-nine place settings in tribute to female historical figures, yet only one of these was for a woman of African descent, Sojourner Truth. At the right, a towering Black woman artist in a dress embellished with wooden fish and a painted expanse of bluish water replaces Hogarth’s standing Black male servant. Alluding to the Middle Passage, Himid turns Hogarth’s critique of over-consumption and greed into a broader moral commentary on the British slave trade.

Himid’s ‘Real World’ section FIG. 12 continues this engagement with histories of slavery and migration, placing them in relation to a critique of conservative British politics. On the far right of the installation, is the ‘right-wing sycophant’/young MP [Member of Parliament]’,34 who replaces Hogarth’s heavily made-up French hairdresser. He responds ‘enthusiastically’ (with an erection), to Margaret Thatcher, one of the largest figures in the group,35 his flex-ready appendage giving him the appearance of a cartoonish marionette, a political puppet who maintains a sycophantic relationship with Thatcher and with the larger Conservative party. Thatcher, who replaces Hogarth’s countess, is seated opposite a reclining Ronald Reagan, who takes the position of Silvertongue. Himid wrote that London during the 1980s was ‘hedonistic’, greedy’ and ‘opportunistic’, referencing the capitalist-driven policies of both Thatcher and Reagan, and images of the ‘special relationship’ that dominated the global press.36

Satire and critique

Himid’s insertion of contemporary 1980s politics into the work aligns closely with Hogarth’s œuvre as well as with later, nineteenth-century graphic commentaries by the Georgian caricaturists James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. Reflecting on A Fashionable Marriage, Himid has noted that there was ‘something rich and quintessentially English’ about Hogarth, who had ‘no qualms about heaping ridicule upon aristocratic architects, politicians, moneyed men [. . .] avaricious families, lazy bureaucrats’; she stated that, ‘in 1986 I wished to do the same [. . .]. His theatricality and storytelling tableaux fulfilled my desire for spectacle and drama’.31 Himid thus forged an alliance with the eighteenth-century painter and engraver based on their wish to critique, through a satirical and dramatically expressive lens, the London of their respective times.

Taking Hogarth’s images as her template, Himid replaced each figure in ‘Scene Four’ of Marriage with one of contemporary topical interest, highlighting the challenges that artists of colour faced, particularly in relation to smaller allocations of ‘Black arts’ or ‘ethnic arts’ funding in Britain.38 Hogarth employed figures of African descent to highlight immorality in their respective contexts. In Hogarth’s scene, a turbaned young pageboy in the right foreground plays with a collection of objects bought from an auction house and grins as he points to a horned figure, a reference to the Countess’s cuckoldry.39 The boy has a lighter complexion than the older Black man who serves a lady drinking chocolate in the scene behind, and his facial features are markedly different.40 He wears an elaborately wrapped white pugree (turban), possibly signifying South Asian descent, but equally likely to represent the Orientalised African servant figures depicted in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European art.41 His age and ostentatious adornment characterise him as an example of a young male child who functioned as a playful, pet-like accoutrement for wealthy European women, referencing what Catherine Molineux has described as the ‘slave-child-pet parallelism’ that was embedded in European high society by the 1720s. In such images, the violence and trauma of slavery is transformed into the ‘intense emotional relationship’ of pet ownership, with both servants and pets perceived as a stylish ‘form of social currency [. . .] objects consumed and displayed in a semiotic system of status’.42 This is also exemplified in John Eccard’s portrait of Lady Grace Carteret, Countess of Dysart with a Child (possibly Lady Frances Tollemache), a Black Servant, Cockatoo and Spaniel (c.1740, FIG. 13) in which the servant child functions as a marker of wealth and status, and is also aligned with the exoticism of the pet cockatoo.

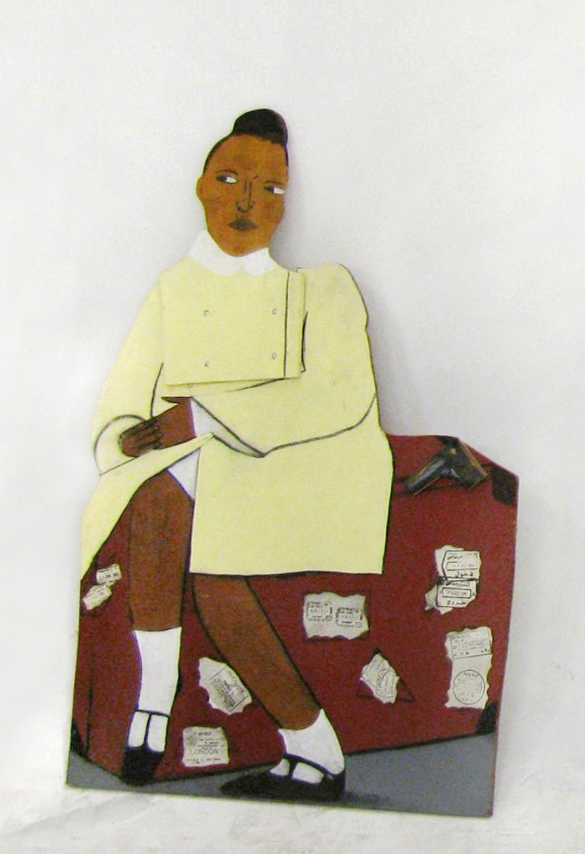

In Himid’s Marriage, the male child becomes a young girl seated on a battered brown suitcase with a handgun resting ominously on top FIG. 14.43 The figure is based on a photograph taken at Glasgow Zoo of a young Sulter FIG. 15, who was of Scottish and Ghanaian heritage. Himid pointedly highlights how colourism sometimes played a role in the selection during the period of enslavement of certain light-skinned or mixed-race children to function as ‘pretty young playthings’. As Himid recalls, ‘Hogarth’s child was a rather sensuous little creature, like decoration. Maud was also very beautiful and no one took her particularly seriously. To some, she was just a pretty thing in a room’.44 And yet, Himid refers to this figure as ‘Ka—the Spirit of Resistance’ – based on the ancient Egyptian concept of Ka as spiritual essence, marking the difference between the living and the deceased, with death occurring when ka leaves the body.45 Himid asserts that, accompanied by a handgun (signifying subversion and self-protection) and a suitcase (plastered with evidence of international travel), the young girl represents a more active and aggressive form of resistance than the mainstream-centred efforts of the Black artist who ‘pours energy and time into white art institutions and systems of approval and reward’.46

The figure of Ka also bears a striking resemblance to certain news agency photographs that documented mass migrations from the Caribbean into Victoria, Paddington and Waterloo stations in London after Britain recruited from its former colonies to rebuild the nation after the Second World War. In 1984, two years before Himid completed A Fashionable Marriage, Stuart Hall published an essay examining the photographs of migrants published in the 1950s, such as Haywood Magee’s photograph of a seated woman at Southampton station.47 These oft-reproduced images operate sentimentally, documenting individuals poised in that most transitory of spaces, a railway station. Himid’s use of the suitcase as symbol of the post-War migrations, and as a symbol of chosen migration and agency, is critical here.

When A Fashionable Marriage was first shown, in 1986 at the Pentonville Gallery, London,48 its satirical nature aroused a great deal of controversy. For example, Sarah Kent wrote in Time Out:

To the Black artist the white world clearly looks a dismal place in which everyone is conspiring to keep her out [. . .] what ultimately weakens the piece, though, is that Lubaina spits her rage and sprays her bullets too widely. In denouncing absolutely everyone except the Black artist she paints her own halo rather too golden.49

The anger that Himid’s Hogarthian critique of the London art world inspired led to a major shift in the artist’s practice, prompting her to leave London and move to northern England. This experience also suspended her interest in cut-outs, which she did not produce again until nearly ten years later. Himid recounted that she never attempted to place the work in a collection: ‘it was greeted with horror, because you don’t see work that was that critical [. . .] that kind of critique of white society’.50For Himid, the long British tradition of satire was crucial to the form of the work, and thus to its interpretation: ‘It was meant to be like Cruikshank and other satirists I loved [. . . ] meant to critique the art world and the political world’.25 In fact, Himid’s drawing style, attached to the cut-out wooden structures, pictorially refers to these graphic precedents in their use of text and in the caricatured presence of figures such as the reclining Reagan.

The cut-out as theatrical device

Himid’s use of the cut-out shifts her images into another realm, as she creates tactile bodies that assert a physical presence, a form that may have contributed to the level of criticism that she received. As the figures approach something closer to reality than a two-dimensional painting, they are intentionally confrontational, forcing viewers, perhaps, to acknowledge their own place in such racialised systems. The connection between A Fashionable Marriage and theatre was first made in Fort’s 2001 article, the subtitle of which – ‘A Post-Colonial Hogarthian “Dumb Show”’ – highlights the work’s underlying performance-based presentation, linking it to the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English dramatic practice defined as a section of a play that is performed in pantomime. Little has been written, however, on the work’s formal and conceptual connections with dummy boards. Produced throughout Europe FIG. 16 and the United States until their popularity declined in the nineteenth century, these freestanding cut-out figures:

were made for many reasons; as visual jokes, as covers for empty fireplaces in the summer and as companions. They were often servants; gardeners, maids, cooks, footmen, sometimes soldiers, sometimes peddlers and even saints. They advertised army recruiting offices, they used to guard doorways and as theatrical extras to advertise tobacco and snuff.52

Also called ‘silent companions’, the figures functioned ‘in service’ FIG. 17, as entities that engaged with notions of the decorative and as markers of wealth (when employed in moneyed residential estates), an association that fits snugly with Himid’s overarching themes.

In their form, Himid’s cut-outs are marked by a layered textural complexity, often incorporating an expressive drawing style, collaged elements and scribbled, graffiti-like text. They appear hastily executed with rough edges, errant nails and jagged cuts of wood, in keeping with their conception as a form of theatrical prop, meant to be seen from a distance. Himid has remarked that ‘Because of the theatre design, I made them to be temporary. They were not built to last. Built just for a show [. . .] it’s about impact and experience and then it’s gone’.53 For this reason, there is a rough and slightly unfinished quality to some of the works, and the evidence of their making is apparent.

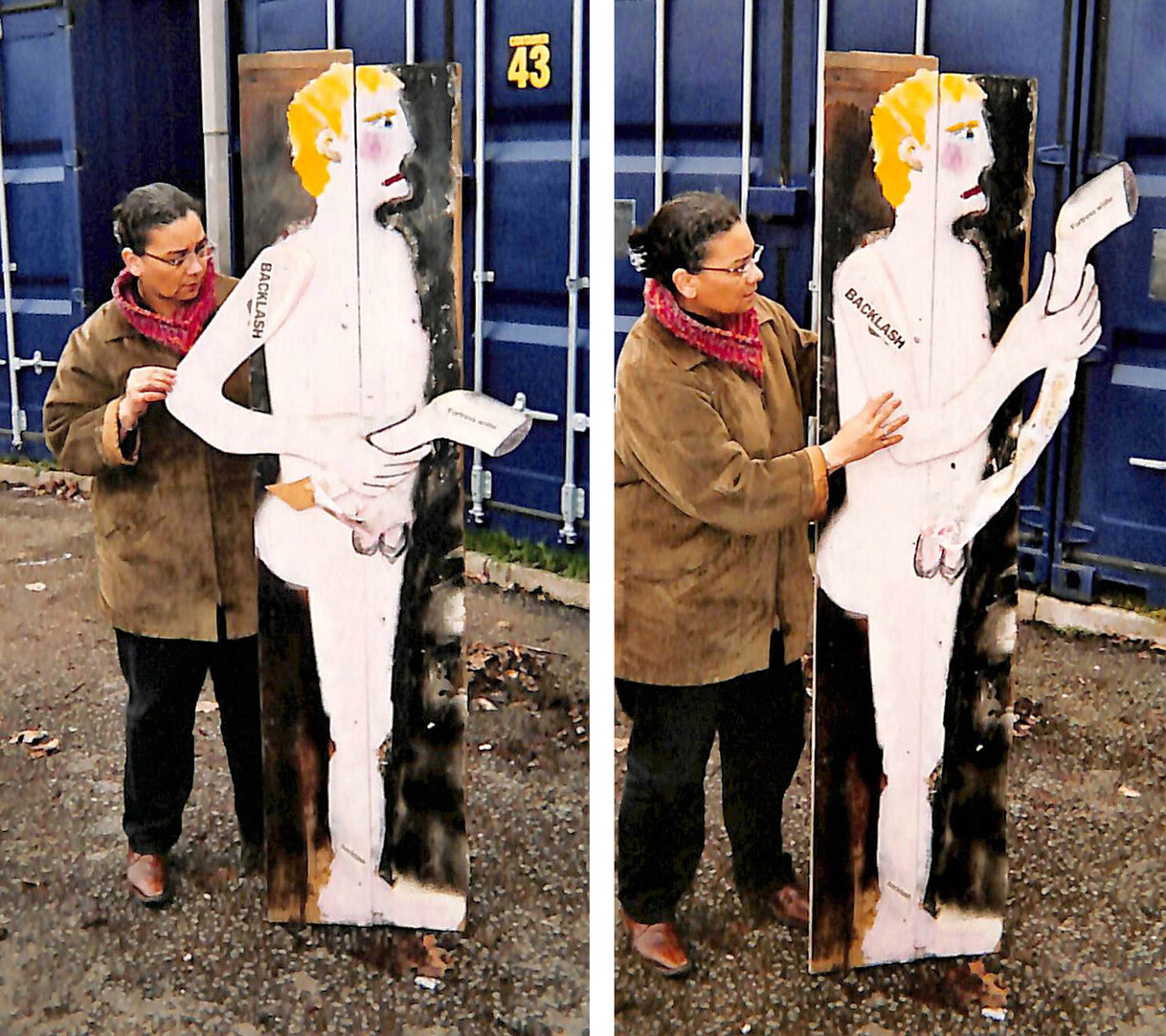

The cut-out form also allows for movement that is employed for satirical purposes. In the photograph above FIG. 18, Himid demonstrates the MP’s swinging appendage, an arm that swings back and forth in a masturbatory fashion. In addition, Hogarth’s male character that stoops to serve the European woman dressed as a shepherdess at his right is replaced by Himid’s ‘Black woman artist’ who, in contrast, tosses liquid into the face of the exclusionary American artist with a swinging wooden arm. This recalls the historical function of many of these figures: to serve as decorative elements that would amuse or frighten guests because of initially being perceived as real.

Himid has noted that her cut-outs were meant to be viewed from the front, functioning much like theatrical placards. She has also described them as ‘history paintings, portraits, political treaties, stand-ins, adverts and effigies. I know what they are not: sculpture. I’ve made more than 200 of them in the past thirty years [. . .] and even though these are more free-standing than they have been before, they are paintings’.54 Her insistence that these works are paintings is perhaps an attempt to move beyond the rigid, structured formality (and ‘fine-art’ hierarchies) of traditional painting on canvas, but also to continue her reworking of history painting, in terms of form, subject-matter and experiments with scale.

Naming the money / Gifts to kings

Himid’s engagement with cut-out figures and theatrical performance was significantly developed in the installation Naming the Money FIG. 19, which was first presented at the Hatton Gallery, Newcastle, in 2004, and more recently at Spike Island, Bristol, in 2017.55 The installation includes one hundred life-size cut-out figures, framed collages on paper and a soundtrack featuring music and spoken narrative. It represented Himid’s return to the cut-out form after a ten-year hiatus.56

The installation highlights, in Himid’s words, ‘how the moneyed classes all over Europe have spent their loot, flaunted their power and wealth by using Africans as slaves [. . .] dressed in the clothes of courtiers [. . .], useful as the greatest conspicuous display of wealth imaginable’.57 She assigned West African, East African and Muslim names (and accompanying personal narratives) to each of the one hundred figures. She also assigned each an occupation and divided them into ten groups: ‘ten ceramicists, ten Viola da Gamba players, ten drummers, ten dancing masters. So each of those people has a story’.58

Himid’s training in theatre design is certainly in evidence here: Naming the Money creates a colourful and crowded environment reminiscent of an urban marketplace, as each figure appears to be involved in the process of selling various wares and/or displaying skills in performance. Compared with the more passive, set-design-like Fashionable Marriage, Naming the Money is immersive, with music and Himid’s spoken narrative playing as viewers, who ‘were supposed to be amongst all the figures’ explored the life-size forms.59 This may reflect Himid’s attitudes towards theatre, which she thought of as:

more real than art in galleries [. . .] I saw theatre as something you could do in the streets, and something that you did with found objects [. . .] a kind of political activism, not necessarily something that you did in a theatre with velvet seats.60

Hence we might consider Fashionable Marriage as an early rendering of a dramatic setting and Naming the Money as a more spectacularised and immersive experience of the space, reflective of Himid’s belief in theatre, and especially its immersive potential, as a form of political agency.

Both installations engage with notions of the carnivalesque and of the decorative. Naming the Money, with its colourful, teeming crowd, speaks most closely to the carnivalesque, and it includes a striking series of expressive, commedia dell’arte-inspired Harlequin figures. Again, Himid’s engagement with a European history of art (and theatrical performance) is critical to her postcolonial message. The collages that Himid produced for the installation FIG. 20 FIG. 21 bear striking compositional similarities to Inigo Jones’s costume designs, as seen in his design for a masquer from the Masque of Blackness, which was performed for King James I and Queen Anne of Denmark in 1605 FIG. 22.61 Indeed, Jones’s masque productions, with their incorporation of music, dance, extravagant costuming and, sometimes, special effects, has been a central influence for Himid, who had initially planned, in 1976, to write her MA dissertation on ‘Inigo Jones and the Stuart court’.62 Himid noted that she was enamoured with:

the way the scenery is designed all flat and painted a la trompe d’oeil [sic], the way costumes are constructed; all flowers and fabric, frills and layers [. . .] the dissertation is going to be about the money spent on these masques, not just the look of the final project [. . .] If you spend this much on a theatrical idea, it becomes about money and not about poetry and love anymore.25

A Black British presence

In 2007 a selection of figures from Naming the Money was exhibited as part of Uncomfortable Truths: The Shadow of Slave Trading on Contemporary Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.64 Appearing in unexpected spaces in the galleries, the solitary characters appeared disjointed, functioning as a form of ‘break’ or interruption in the ‘official narratives’ of art and design history at the museum, a key theme in Himid’s œuvre. Yet the installation was presented in a way that likely most closely resembled the experience of encountering dummy boards in their original contexts.

In both installations, Himid (like Hogarth) employed a theatrical presentation of figures of African descent as a form of moral critique, interrogating Britain’s colonial and imperial past as well as its twentieth-century race-based challenges. A Fashionable Marriage engages with Hogarth’s stage-like scene in all its symbolic ambiguity and narrative possibilities, visual and verbal puns and complex markers of class, gender and race. In Naming the Money, Himid constructed a somewhat confrontational, or embodied, sense of a Black British presence,65 one that named, and provided a personal narrative and sense of humanity for, African descendants who had long been perceived in monetary terms.

In her use of the cut-out form, Himid has activated, or animated, the history of a Black presence, critiquing the notion of global Black bodies as ‘presents’ or commodities, while drawing on themes of visibility and invisibility; the ‘real’, the illusory, the representational; and loss and remembrance. The cut-outs provide us with an opportunity to engage with these historically ‘silent companions’ who have, through Himid’s spectacular productions, become much more visible and certainly less silent.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a broader study that is drawn from my 2011 PhD dissertation, ‘Hogarth’s progress: “modern moral subjects” in the work of David Hockney, Lubaina Himid and Paula Rego’, (Duke University, Durham NC, 2011), as well as a paper, '“Silent companions”: staging Lubaina Himid’s "Fashionable Marriage" (1986) and "Naming the Money" (2004)', presented at the College Art Association annual conference in New York, 13th–16th February 2019. I am extremely grateful for the gracious assistance of Lubaina Himid, who has provided me with a wealth of insightful and highly illuminating interviews since the mid-1990s. I also acknowledge and greatly appreciate the support and enthusiastic assistance of Janice Cheddie and Rita Keegan.

woman in black, 1982. arts council collection, southbank centre, london c. claudette johnson.jpg)