Creativity of practice in African townships: a framework for performance art

by Massa Lemu • May 2019 • Journal article

Eurocentric aesthetic and theoretical frameworks have long been used in critical and art-historical writing on African art, obscuring it with colonial epistemological matrices that are difficult to shake. However, some artists and curators on the continent, including Bernard Akoi-Jackson, N’Goné Fall, Khanyisile Mbongwa, Jelili Atiku and Sethembile Msezane, who gathered at the Live Art Network Conference in Cape Town in 2018, insist that, rather than drawing influences from Western models of art history or theory, their practices are shaped by everyday life in the townships.1

The call to decolonise cultural production is not a new phenomenon in intellectual circles in Africa. Since the 1960s, particularly in the wake of the debates about decolonising African literature at the ‘Conference of African Writers of English Expression’ held at Makerere University, Kampala, in 1962,2 writers and theorists have sought to find an appropriate vernacular with which to describe and reflect on life in Africa. Philosophers who have engaged with the issue of African modes of self-writing – theorising or narrating the self as a process of subject-formation – include Achille Mbembe, V.Y. Mudimbe, Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong’o, Chinweizu, Njabulo Ndebele and Manthia Diawara.3 For example, in his essay ‘African modes of self-writing’, Mbembe encourages fellow philosophers writing about Africa to pay attention to

the contemporary everyday practices through which Africans manage to recognize and maintain with the world an unprecedented familiarity – practices through which they invent something that is their own and that beckons to the world in its generality.4

What Mbembe describes elsewhere as ‘creativity of practice’, defined as the ‘ways in which societies compose and invent themselves in the present’,5 provides a framework for understanding how the people actively rewrite their histories and invent their futures.6 Focusing on the work of Gugulective and iQhiya of South Africa and Mowoso of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), this article seeks to show how creativity of practice, understood as diverse inventive actions deployed in African urban spaces by urban dwellers, inspires certain strands of performance art emerging on the continent. Since it foregrounds process and action, and activates bodies in space and time, performance – particularly the live kind situated in everyday life – is the art form most proximate to creativity of practice; it holds potential for subject-empowerment and resistance under dispossession.7 As poetic reflection on, and re-articulation of the practice of everyday life, performance opens up avenues for imagining other ways of being.

The three groups Gugulective, iQhiya and Mowoso engage a subject-forming aesthetic of resistance rooted in and shaped by daily life in the city. Collectivism is key to this conception of creativity of practice, which is characterised by collaboration and a subject-centred communality that counters the hyper-individualism that defines and is promoted by the neoliberal art-world. The term ‘creativity of practice’ does not claim to describe every facet of these highly complex art practices, which might also be psychic, spiritual or metaphysical, rather, it highlights an important material dimension that ties this work to its social-political contexts. Other social practices that have shaped performance in African art include traditional ritual, magic, religion, masquerade and dance.8

Material context

Neoliberal capitalism, as it is exerted by the state, multinational corporations, humanitarian aid and Pentecostalism, forms the broader socio-political context of creativity of practice. A product of colonialism, the township in African cities was designed to deposit, contain, segregate and exploit Black labour.9 Decades after supposed independence, little has changed: the township maintains its status as a space for the marginalisation, exclusion and exploitation of Black bodies, now overseen by a Black bourgeoisie working in the service of global capitalism. Although this is more conspicuous in Cape Town, it is also the case in Harare, Blantyre, Kinshasa, Nairobi and Lagos. Creativity and inventiveness are therefore deployed by township dwellers in order to overcome daily frustrations and such phenomena as environmental degradation, privatisation, corporate scams, corruption, precarious jobs, retrenchments and debt. These actions, which James C. Scott describes as the ‘weapons of the weak’, include the illegal tapping of water and electricity; moonlighting (for those fortunate to find jobs); dissimulation (i.e. pretence or ‘faking it’ as a mode of empowerment, as is the case with the SAPE dandies of the DRC discussed below); social media memes (to mock and find humour in the follies of the powerful); the advance-fee frauds known as 419 scams; witchcraft (for example the use of charms to fend off adversaries and ill-fortune); pilfering (at the workplace to supplement meagre wages); and nomadism to escape township misery, injustices and suffering.10 Together, and in tandem with formal activism, these minute instances of resistance can counteract oppression. This is not to say that township dwellers subscribe to grand anti-capitalist ideologies in their everyday acts of resistance, but to emphasise their agency as they react to the forces that shape their lives.

The artists discussed here draw from these activities not in mimicry but in order to radicalise and energise their art as resistance and re-existence.11 Their performances, which often feature play, humour and the absurd, demonstrate creativity of practice as a mode of thinking, seeing and doing concerned with the role of irony and wit in political agency. If ambivalence, the unpredictable, the surreal and even failure are alive in people’s everyday experiences, can they continue to be important strategic devices in socially engaged art?12

Mikiliste cosmopolitanism

The work of Mowoso collective, which was active in the townships of Kinshasa in the DRC between 2007 and 2011, drew its strength from precisely this context.13 In DRC townships, escape, whether imaginary or real, is articulated in the mikili or SAPE (Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes) culture, which is prominent among urban Congolese youth FIG. 1. Derived from the Lingala word ‘mokili’, which means ‘world’, mikili or mikilisme describes a culture known for its sartorial elegance. The mikiliste or sapeur imitates European bourgeois lifestyles in dressing, speaking or eating FIG. 2. Mikilisme is adopted primarily by young people who wish to flee the poverty that surrounds them by relocating to a European metropolis, particularly to Paris.14

Mikili are perpetually on the move, between the slum and the city, or Kinshasa and Paris. Encapsulating the precarity and mobility that define the contemporary global condition, mikilisme is thus a cosmopolitanism shaped by colonialism, neocolonialism and the ravages of neoliberal capitalist globalisation on the African continent.15 Mikilistes are believers in this cosmopolitanism. But mikilisme does not just describe a belief, it is also a set of urban practices with certain characteristics, aims and objectives. The series of performances titled Blue Boys (2006) FIG. 3 by Dikoko Boketshu of Mowoso is a comment on this culture.

Clad in blue denim jeans and leather jackets, the mikiliste ‘Blue boys’ cuddle furry terrier dogs FIG. 4 and show off Versace labels FIG. 5. While Blue Boys captures the flair and flamboyance of the flashy sapeur, the performers are not draped in the usual couture of designer suits, fur coats and bow ties loved by the latter. The rugged and worn clothing of the Blue boys seems to have been sourced from the second-hand clothing markets abundant across Africa. Boketshu’s exaggerated and absurd poses, set against dirty walls, trash and cesspool-ridden backgrounds featuring nonchalant underfed children, provide a satirical, if ambivalent, critique of sapeur performance. Moreover, the piece incorporates an incisive critique of the well-documented controversy surrounding the global trade of recycled clothing choking the African textile market.16 The work asks an important question: to what extent can mimicry be empowering and redemptive?

The news is the war

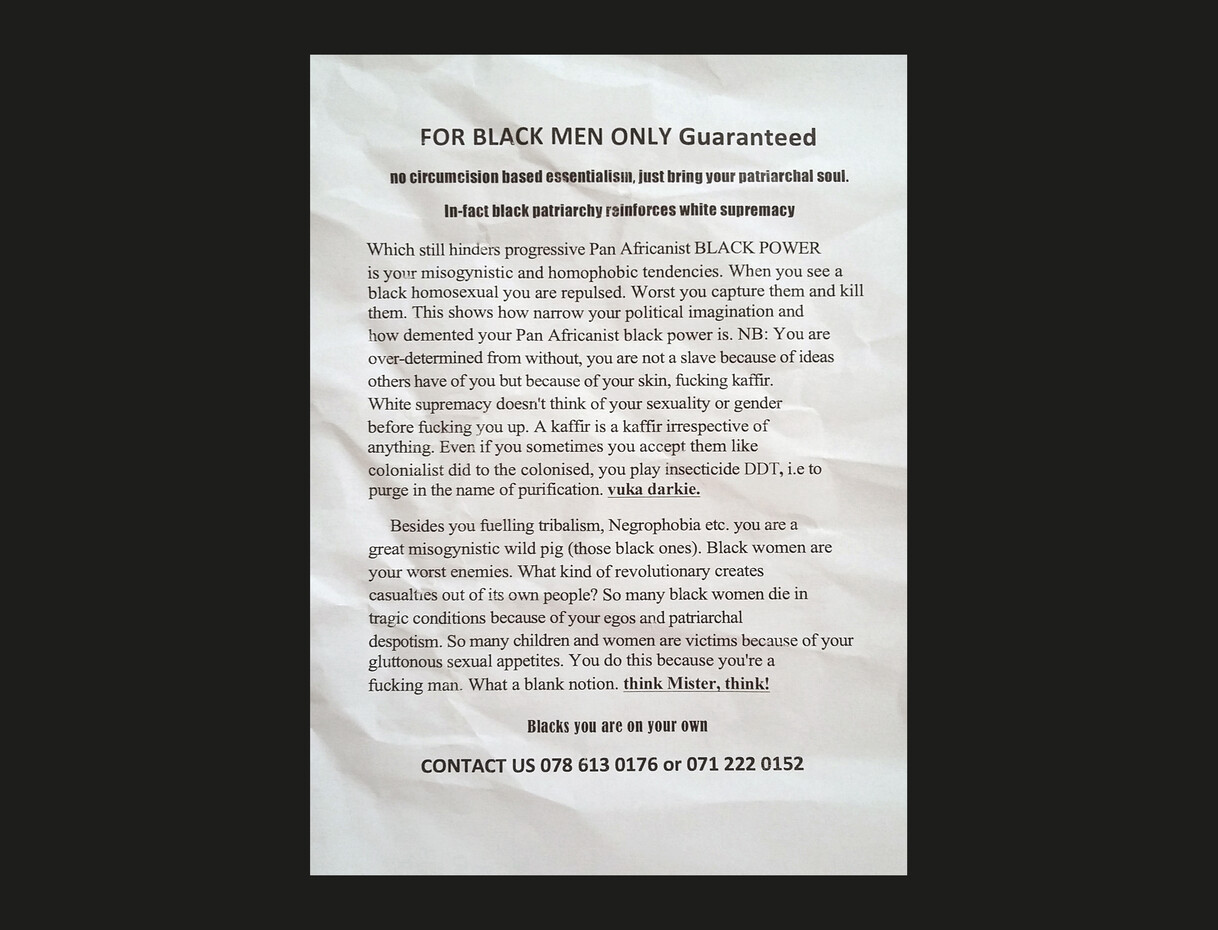

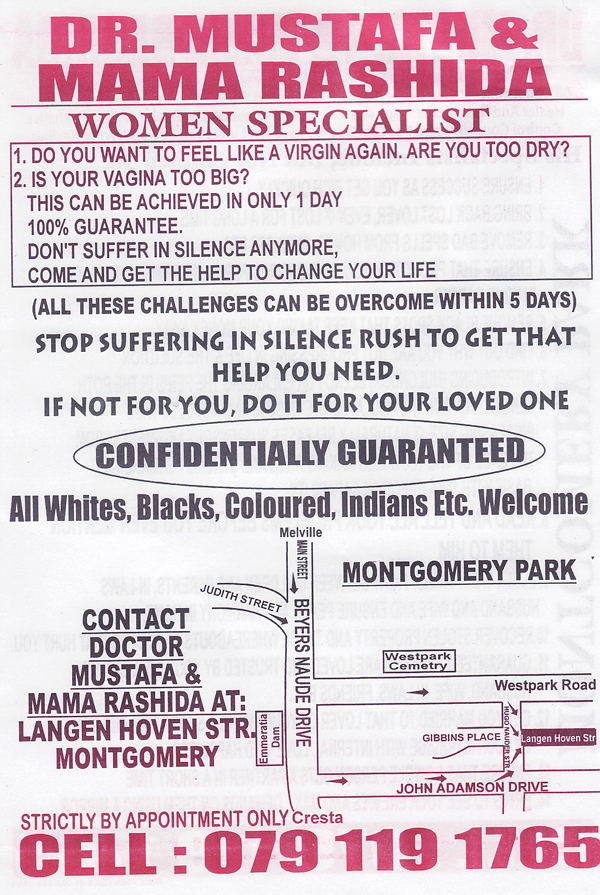

In its peak period of production between 2006 and 2010, Gugulective was a collective of eight artists and writers from Gugulethu, a township located to the east of Cape Town, who used a shebeen as their hub. Shebeens are gathering spaces where, during apartheid, illegally home-brewed beer was sold. These politically charged spaces were banned by the apartheid regime to control and prohibit informal political gatherings by Black South Africans. Gugulective’s art dealt with Black lived experience in the township. For instance, the flyer used in the performance Indaba ludabi FIG. 6 borrows from and plays with the language of the ubiquitous sangoma (traditional healer or witchdoctor) advertisements, which are regularly to be found pasted in township spaces and commuter trains FIG. 7.

Gugulective’s use of vernacular titles in their work is a notable decolonial strategy. ‘Indaba ludabi’ is an isiXhosa phrase, and roughly translates as ‘the news is the war’, possibly in reference to the regime’s use of the media as channels of disinformation in its subjugation of Black people.17 In countering these strategies of domination, Gugulective took the format of the healer’s advertisements – a good number of which are scams – as the template for Indaba ludabi. Gugulective’s flyers, which replace the healer’s promises with political messages, were handed out to passers-by outside Museum Africa in Gauteng, Johannesburg, in a performance by some members of the collective. The revolutionary aesthetics of the work – low-cost one-page flyers and the simple action of handing them out – is clearly inspired by township people’s technologies of resistance, as well as more direct political action, since the flyer also recalls the leaflets and posters used during the anti-apartheid struggle. The flyer’s urgent political content is interlaced with dark humour and a biting critique of class, race and gender: ‘Besides fuelling tribalism, Negrophobia etc. you are a great misogynistic wild pig (those black ones)’. In Indaba Ludabi, action replaces contemplation, the ephemeral is valued above the permanent, the participant rather than the art object is primary, and the street is preferred over the art gallery.

Marikana we are here!

Where domination ratchets up violence, creativity of practice emerges in instances of militant protest. For example, in 2011 the protesters at Tahrir Square in Cairo created a system for sharing electrical power communally, which they used to charge mobile telephones for communication and networking that was crucial to the Arab Spring. It was also exemplified in the tactics deployed by the Marikana miners striking in 2012 against the ruthless regime determined to safeguard capitalist interests at the British-owned Lonmin Mines in South Africa.18 In the ensuing struggle for a better wage, thirty-four miners were killed and several others injured by police. Marikana Never Again Poetic Procession by Khanyisile Mbongwa, a former member of Gugulective, is a work shaped by the massacre in form and content FIG. 8.

Poetic Procession, which involved visual art, music and poetry recitals in the streets of Cape Town, was curated by Mbongwa and hosted by the Africa Arts Institute. It is an example of art directly borrowing from life in an intervention that sought to insert marginalised bodies in public spaces against regimes of dehumanisation and dispossession. Members of the procession wore black pants and black T-shirts emblazoned with images of Mgcineni Noki, a leader of the Marikana miners who was killed in the police attack, framed by the words ‘Remember Marikana’. Some also wrapped themselves in green blankets similar to the one Noki was wearing when he was killed. Among South African artists such as the Tokolos Stencil Collective, the figure of Noki has become a symbol of the anonymous Black worker whose labour is exploited by rent-seeking multinational corporations.19 Displayed in some parts of the city were banners that read ‘Sharpeville Never Again. Marikana. Again’, or ‘Miners down. Profits Up’.

The procession comprised a group of about twenty artists, poets and musicians, who were led around the streets of Cape Town by Mbongwa as she spoke intermittently through a megaphone.20 As they marched, the members of the procession raised picture frames, some containing religious images, and some empty, in reference to the absent miners. They hummed mournful dirges as Mbongwa read the names of the slain leaders of the strike. Mbongwa was interrupted several times by a siren when trying to speak through the megaphone, alluding to the violent muzzling of dissatisfied and dissenting voices in the South African democratic dispensation.

During the procession, when Mbongwa emphatically shouts ‘Marikana we are here!’, she is not only asserting the presence of the protesters but also registering the people’s impatience with continual state-sanctioned violence and brutality. Almost twenty years after Nelson Mandela led the country from white apartheid rule to democracy, the state-sanctioned Marikana massacre highlighted that little had changed. In post-apartheid South Africa, the new Black leaders all too often assumed the role of a comprador elite under the supervision of neoliberal white monopoly capital. It is important to note that Cyril Ramaphosa, the current president of South Africa, was on the board of Lonmin during the strike and has been implicated in the massacre.21 For Mbongwa, therefore, ‘Marikana is the mass-murder of our time as post-apartheid youth – that marks how liberal economy continues to enslave the black body, rendering it disposable. It plays out the relationship between government, transnational companies, and capitalism’.22 Bulelwa Basse, one of participants in the procession, recited a poem for the voiceless and oppressed, to encourage creativity as a means of self-formation and empowerment:

I wish for you to create your own

Leap toward incandescence within yourself

That you may arrive to love unlimited

That you may arrive to self . . . 23

Although Poetic Procession was commemorative of the massacre, Mbongwa prefers to describe it as an intervention to underline its quality as an actual event rather than merely a symbolic representation.24 Thus operating inbetween art and protest, Poetic Procession is a singular instance of creativity of practice intervening in normalised dispossession and dehumanisation.

Poetics of visibility

Creativity of practice also manifested itself in the South African student movement of 2015, which has been dubbed the ‘fallist’ movement after their demands that ‘fees must fall’. The widespread anger and discontent that had been fuelled by the Marikana massacre permeated universities. In 2014 the Tokolos Stencil Collective had revealed that Lonmin was a sponsor of the University of Cape Town, exposing the university as a beneficiary of Black oppression and exploitation.25 In the fallist movement, which was a culmination of these different strands of discontent, text, performance and installation were garnered in the fight to decolonise the exclusivist neoliberal university. iQhiya, a collective of eleven women artists that emerged from the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art around the same time, takes its name from the headgear that African women use both as a fashion accessory and as cushion for carrying heavy objects. In a series of works titled Portrait (2016), the collective, all clad in white, stand on or next to red soda crates for as long as they can endure FIG. 9. The group return the (predominantly white) viewers’ gaze as they menacingly brandish unlit Molotovs, merging art and militant protest in the fight against the marginalisation of Black women – Nomusa Makhubu calls this merging of art and protest for political ends ‘militant creative protest’.26 The iqhiya headpiece adopted by the collective represents the most apt symbol for the practice of everyday life. In Portrait, the iqhiya is stuffed in the Molotovs with which the performers intend to attack the exclusivist art institution. Staged in multiple art venues in South Africa and abroad, including at Documenta in Athens, the young Black women therefore symbolically take over, in order to decolonise the predominantly white spaces of the art world.

Portrait also comprises a wider critique, of the objectification and commodification of Black women’s bodies outside the art world. The performance was inspired by a photograph from a member’s family album, in which a group of older aunts strike defiant but elegant poses.27 For iQhiya, the old photograph represents the beauty, dignity and resilience of Black women who endured oppression under apartheid. Portrait thus echoes Gugulective’s Indaba Ludabi and Mbongwa’s Poetic Procession in its enactment of the poetics of visibility of marginalised bodies in public spaces, foregrounding the body of the artist in interaction with the (implicated) viewer.

Mimicry, militantism, nomadism and escapism are central to instances of self-determination and self-definition such as mikilisme and fallism, through which artists and township dwellers collaboratively construct their own regimes of truths. In discourses oversaturated by Western frameworks, creativity of practice seeks to describe these actions from an African perspective, as a constellation of practices of resistance and re-existence. Collective production is key for this politics of self-empowerment and redemption. Under conditions of dispossession and dehumanisation, creativity of practice describes disparate acts that are linked by what Mbembe would call ‘the refusal to perish’.28 In the art discussed above, these acts are infused with irony, wit and humour to create subversive beauty. In their multiplicity, these actions wear down power by attrition, but it is their creative and life-affirming element that is most valuable.