Closest to nowhere

by Adjoa Armah • November 2022 • Artist commission

The text and images in this commission are part of the installation, the thinking for, ongoing thinking from, and constituent relationships of, the solo (but only as a formality) exhibition <◯><◯> (or less than living more than less than living more than) at fluent, Santander, 2022.

0.

Darling, let us start from nowhere, which is somewhere: a watery location for our fictions and measures. A point of reference for defence contractors and travellers alike, many of whom would have never heard of this nowhere.1 0°N 0°E. Here, prime meridian and equator meet. Some call it Null Island, not land but a point, one of the most visited places on earth, a busy fiction.

I have never been there, physically, to that point on the map, but I have been made to contend with multiple nowheres; many of us have. I have got as close on land as one can to the nowhere of global positioning systems and the conquest of land, sea and peoples. The land closest to this nowhere is Cape Three Points in Ghana’s Western Region. There, atop rock, alongside lush green, before foaming sea, you will find a monument, a tribute:

MAMA AFRICA

Etched into concrete below is an outline of the continent and a list of the constituent nations of the African Union: 1. ALGERIA to 53. ZIMBABWE. The numbering would be different now, nations are not fixed things. There is also a lighthouse and a signpost, telling you how far away locations such as Accra, Lagos, Singapore and Tokyo are. Not listed, though, are the four European-built forts within a 20 km radius of this location and the dozens more along the coast of what is now called Ghana.

I have been thinking about these structures, the forts, visiting them with other artists and scholars, exploring how they knot together the movements of the Black Diaspora across the Atlantic and the African continent. I have been trying to think with the befores of the world that those structures created. In a conversation with the artist Nolan Oswald Dennis, he reminded me: ‘African people have learnt how to move through this world while knowing that this world is not real’.2 I am trying to contend with the afterlives of these structures and the different ways they have acted upon all of us – the fictions too often taken as fact and how they have been resisted. I have been considering what else could be possible from these sites by paying close attention to the land and sea in their vicinity and listening to the histories and stories told by the communities surrounding them.

In her opening chapter to Wayward lives, Beautiful Experiments, an examination of Black intimate life and of freedom, Saidiya Hartman recreates the ‘radical imagination’ of young Black women by ‘describing the world through their eyes’ and writing a narrative from

nowhere,

‘the nowhere of the ghetto and the nowhere of utopia’.3 I am interested in the divergences of nowheres, whose mind creates which, and Black imaginative labour. The land closest to nowhere, en route from one fort to another, captured my imagination and pointed towards how I may be with others. As I try to find a grammar for the form of research within my artistic practice, closest to nowhere is where I felt I could begin. Begin, if not create outright – if there could ever be such a thing – composing with and creating dialogues between the materials, shapes, words and ideas already in the spaces that I both found myself in and wanted to get to. After Torkwase Dyson:

‘In the act of making I understand that it is the integrations of forms folded into the conditions of black spatial justice where I begin to develop compositions and designs that respond to materials’.4

1. ‘sealed till the day of redemption.’5

‘The collection of sands that have been selected chronicles what remains of the world from the long erosions that have taken place, and that sandy residue is both the ultimate substance of the world and the negation of its luxuriant and multiform appearance. All the scenarios of the collector’s life appear more alive here than if they were in a series of colour slides’.6

I have collected sand from the beach closest to the place on land that is closest to nowhere. There are many layers of proximities. I have begun collecting sand from every beach I have identified as being the site – or close to any now lost to sea – of a European-built fort, the vast majority of which housed captured Africans who were to be enslaved, within the bounds of what is now Ghana. There are around thirty remaining, some have been taken by the sea, others the forest, a few destroyed by cannon fire. From Beyin to Keta, 550 km, more or less. I consider these beaches ‘marginalia, a footnote to the essay that is the ocean’.7 In my/our visiting of the forts, I am endlessly consumed by the re-, the again and again, the backwards motions, the redemption,

the repetition,

the remembering,

the return,

the repair,

the repair,

the repair.

‘... making and repair are inseparable, devoted to one another, suspended between and beside themselves’.8

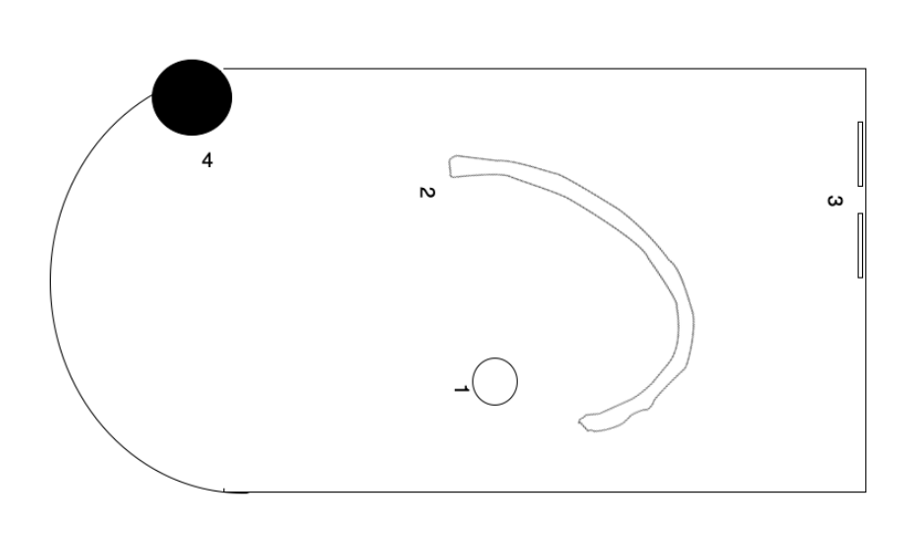

When I was commissioned to produce an exhibition and public programme for fluent, Santander, I began with the sand from the beach closest to the place on land that is closest to nowhere and the potential for transformation. Sand to glass, liquid to solid, commodity to waste, to art object, stranger to collaborator, to friend to family. Each with a distinct relationship with and demand on time. The composition began there, counter clockwise from a testament to time needed, claimed and given, filled with sand from the beach closest to the place on land that is closest to nowhere, encased in recycled glass and named in tribute to the waiting.

These objects, and thoughts and words, have been choreographed for the body to confront a material cosmology where notions of time, cyclicality, scale and transformation reveal a series of wider questions about the construction of race, its historical, epistemological and narrative entanglements. In the exhibition space I want to hold together elements that support me, and hopefully others, in key questions that I have returned to for years.

How do we (Black people) speak to one another? How can I write for, narrate for, the consciousness of The Door of No Return – part of the technical apparatus of the construction of the Black subject – in ways that account for both those that passed through and those that did not?

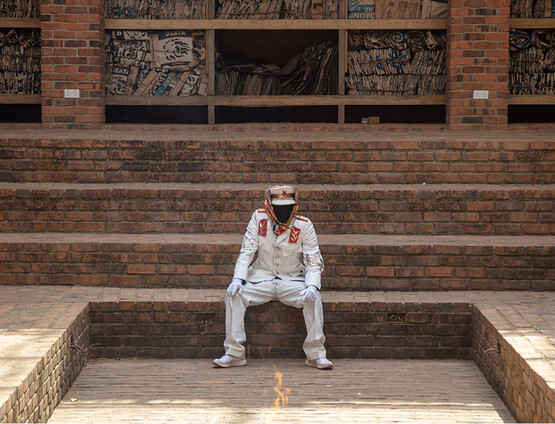

2. ‘despite the pain, she still loved and loves.’9

One’s ending is another’s beginning. The facts of our worlds are propped up by words, by letters, by ideas. Here, the healer’s words hold space:

Darling, it is love that kept you this safe for this long.

At this second point in our choreography, a Cape Coast sand-flecked bench resembles the outline of a human rib. Here is bodyland interrupted by tumorplanet made of chalk, or calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Bodyland, covered in beach fragments, marginalia, pieces of footnotes to the Atlantic’s oceanic essay is propped up by books, the healer’s words reminds us why we are here, allows me to think: be well with others. In this space, a solo only by formality, Fred Moten, Manuel De Landa, Kei Miller, Rachel Carson, Italo Calvino, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Malidoma Patrice Somé, Katherine McKittrick and Domingo Evertsz are physically inserted, holding up and being held by bodyland and tumorplanet. Michael Tetteh, Seah Wraye and a different version of myself are inserted in naming works and points in space. Sel Kofiga is present in physical, creative and intellectual labour as well as emotional support. Owen Green is present in his contribution of scientific and technical knowledge. Nolan Oswald Dennis, Rindon Johnson, Nydia A. Swaby, Eric Gyamfi and Lauren Craig are present in conversations, public and private. You must follow the marginalia and what is coming to know what to make of this growing cast. I want you to consider:

‘What if the practice of referencing, sourcing, and crediting is always bursting with intellectual life and takes us outside ourselves? What if we read outside ourselves not for ourselves but to actively unknow ourselves, to unhinge, and thus come to know each other, intellectually, inside and outside the academy, as collaborators of collective and generous and capacious stories?’.10

There are many more to reference and the boundaries of contribution blur. I/we cannot do this alone. Together we work through Blackness as an analytical category, Black utopias, the material and natural products of historical processes, the points of contact between different epistemologies, the relationship between the ocean and human life, the visual universe and work of the imagination, Black feminist lessons from marine mammals, notions of return and the crisis of spirit, scientific knowledge and the demands made by storytelling, the geological makeup of our planet, what is possible in a single human life,

…,

…,

…,

and what exceeds an individual life.

3. ‘nowhere is never somewhere you get to one way.’11

3.1

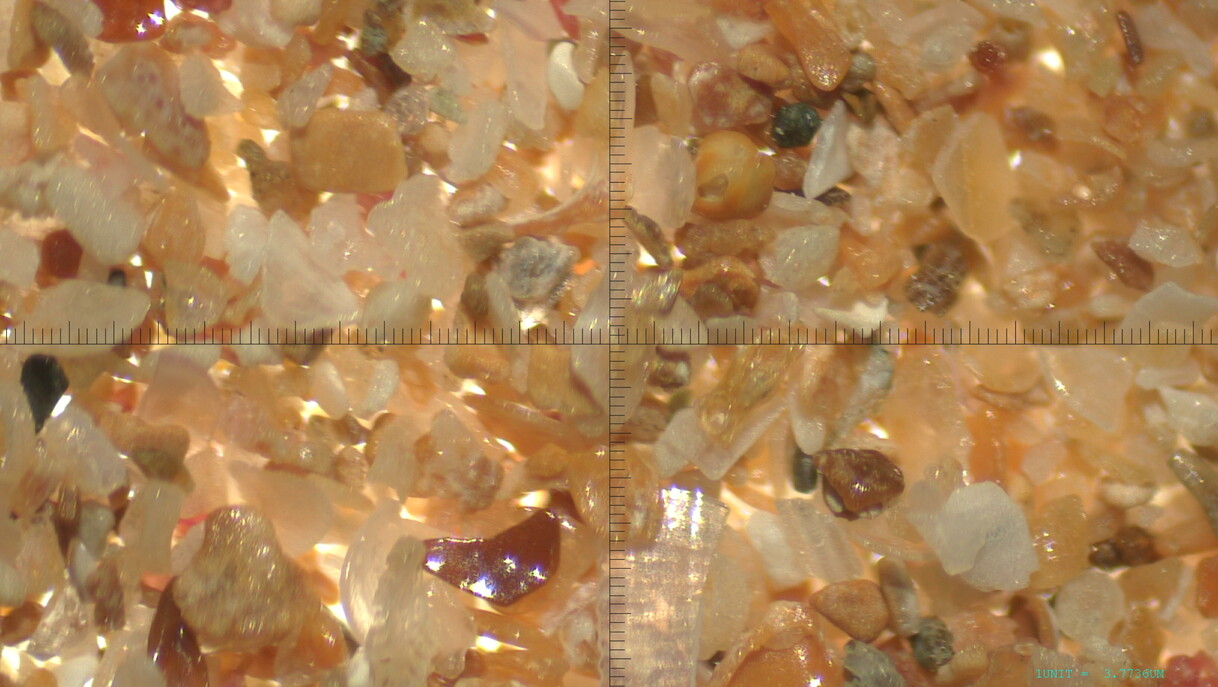

Sample 2: Cape 3 Points [sic]

A bioclastic sand – dominated by calcium (CaCO3) components (95%) derived from a diverse assemblage of marine organisms. Macro- shell material is broken, but the primary colour variations (yellow, pink, purple, white) preserved suggest that movement and exposure has been local. The assemblage consists of mollusc, echinoderm, red algae, smaller benthic foraminifera (Discorbids, ‘Ammonia’ recognisable) – a fully marine environment. The grain size of the components (0.2mm), indicative of a well sorted fine-grained sand. The remaining 5% of the sediment comprises the clastic-arenaceous grains of colourless quartz and black opaque minerals, and is confined to the very fine grain grade.

3.2

3.3

Perhaps when I say route I mean scale too. For Italo Calvino, ‘the geography of the part and that of the whole, that of the earth and that of the heavens, and the heavens can be an astronomical firmament or the kingdom of God’.12 I am interested in all things possible beyond and before this. In the efficacy opened up by quartz, itself a spiritual and navigational technology, a tool for opening, a mineral and resource for technology infrastructure. Extractable, minable, transforming.

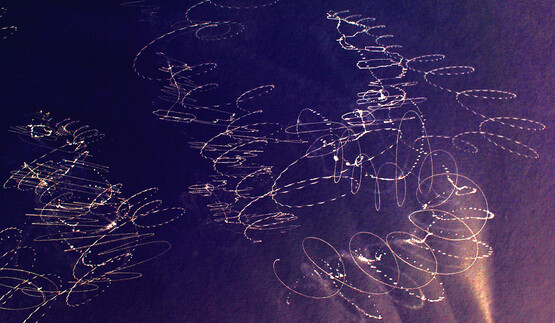

4. this border won’t contain (2022)

‘If I am black, it is not because of a curse, but it is because, having offered my skin, I have been able to absorb all the cosmic effluvia. I am truly a drop of sunlight under the earth….’.13

This is the end of the choreography. A place for the black hole and listening with salt. We can make new beginnings here.