Bruce Nauman: queer homophobia

by Julia Bryan-Wilson • May 2019 • Journal article

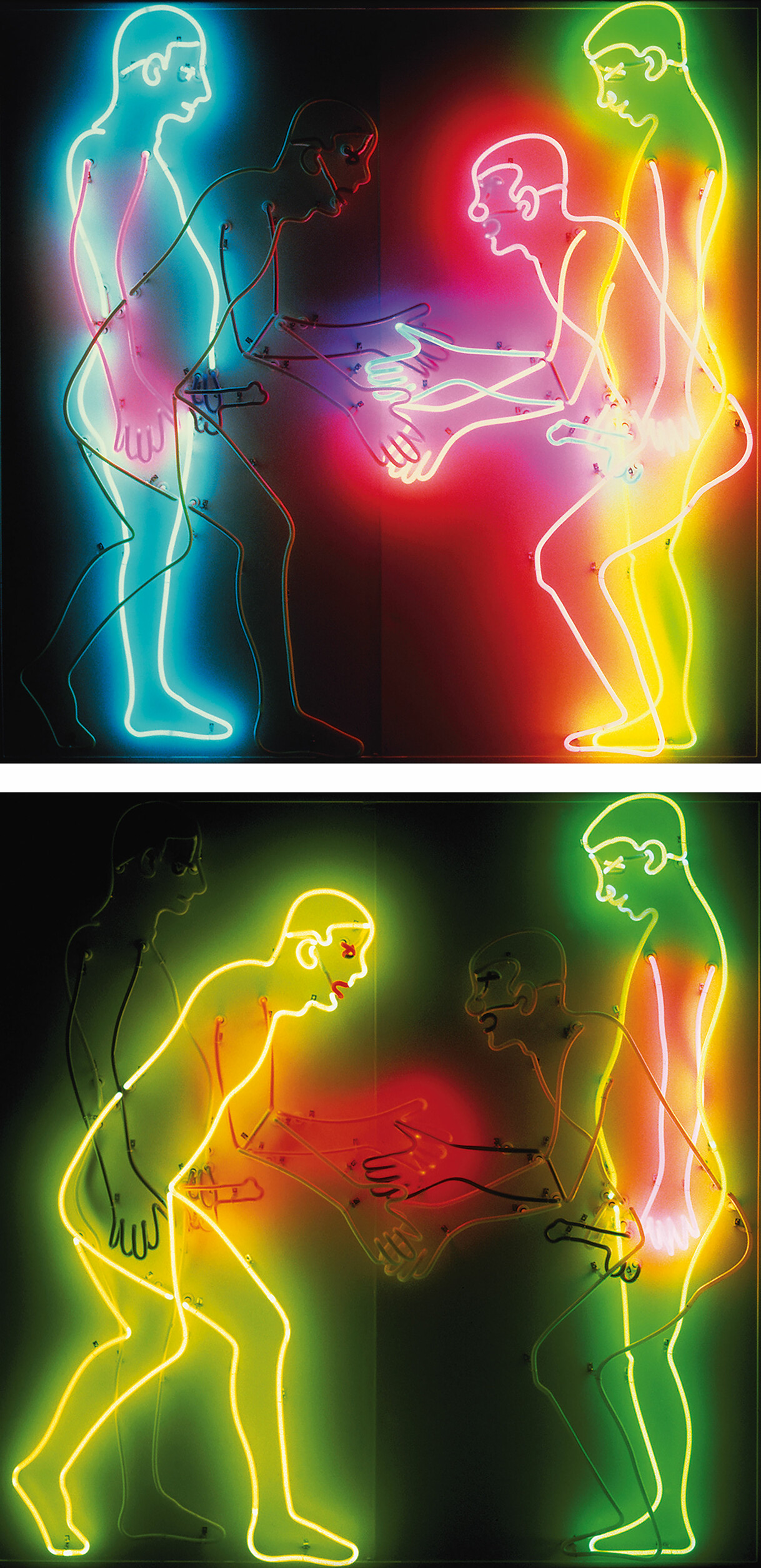

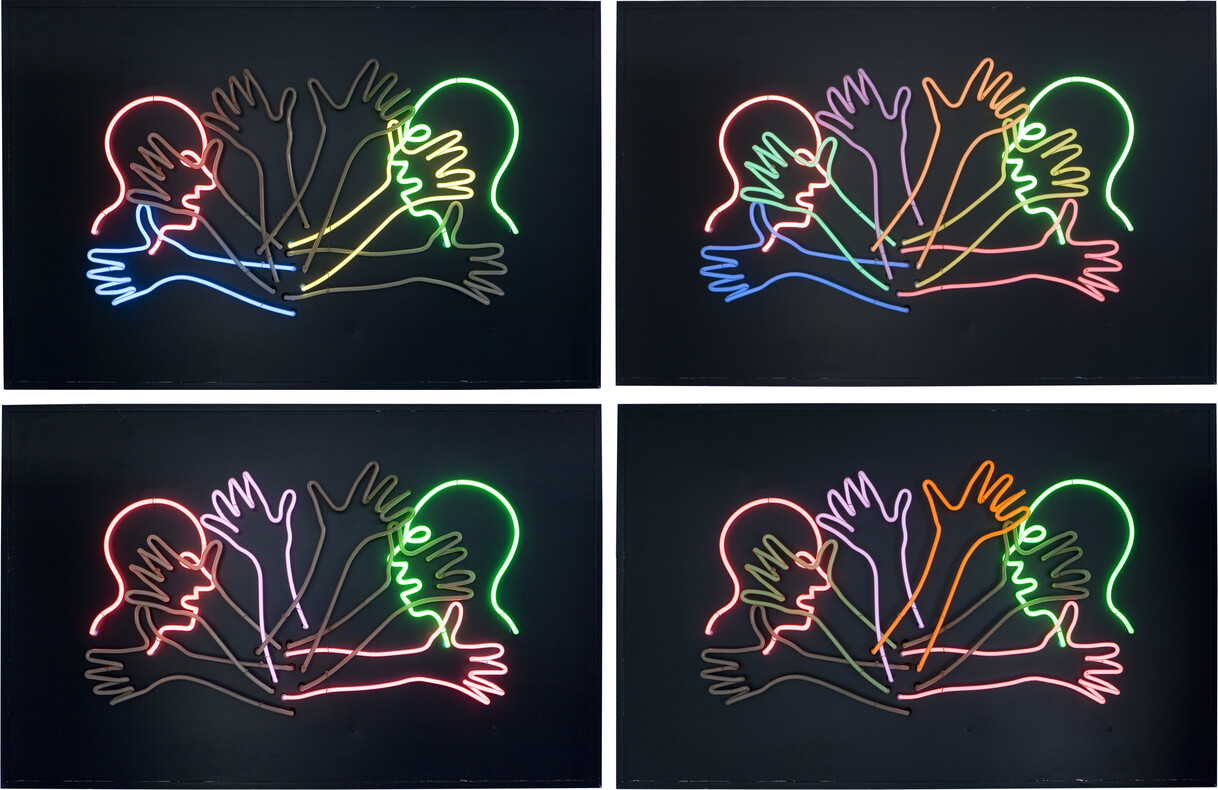

Welcome (Shaking Hands) FIG. 1, one of eighteen figurative neon works Bruce Nauman made in 1985, depicts outlines of (presumably) male bodies facing each other. The lighted tubes sequentially illuminate and then click off, animating the interaction between the men; one moment their arms and hands dangle by their sides, in the next the same arms and hands are outstretched; their torsos alternate between upright and slightly bowed with bent knees. In concert with their extending hands, their penises flicker between flaccid and erect. According to the 1994 catalogue raisonné of Nauman’s œuvre, Welcome (Shaking Hands) was the first of these figurative neon pieces – which resulted from a series of related recent drawings – to be fabricated. It marked the beginning of a flurry of activity in 1985, in which Nauman utilised neon silhouettes largely based on cardboard templates of his own body, continuing his long practice of casting his physical form as a measure or standard.1 In this piece he includes characteristics that signal generic white masculinity – a slightly paunched belly, a few strands of hair. The figures’ facial expressions toggle between small smiles and something less readable – maybe surprise or eagerness, but possibly disgust or even malice.

As the tubes flash on and go dark, the neon functions less like a line drawing than a dynamically moving sequence with a durational flow, a constantly looping narrative that rapidly cycles between poses. In Welcome (Shaking Hands), a conventional greeting of male-to-male social exchange is revealed to be fraught and sexual at its core, as the collegially outstretched hand becomes an analogue for the brightly lit penis that is cocked out at the same angle, and rendered in the same colour, as the forearm. Due to the superimposition of the figures, and the fact that the sequence of animation includes a moment when all the bodies and their parts are simultaneously illuminated, these two pairs of men multiply into a scramble of limbs, torsos, faces and erections.

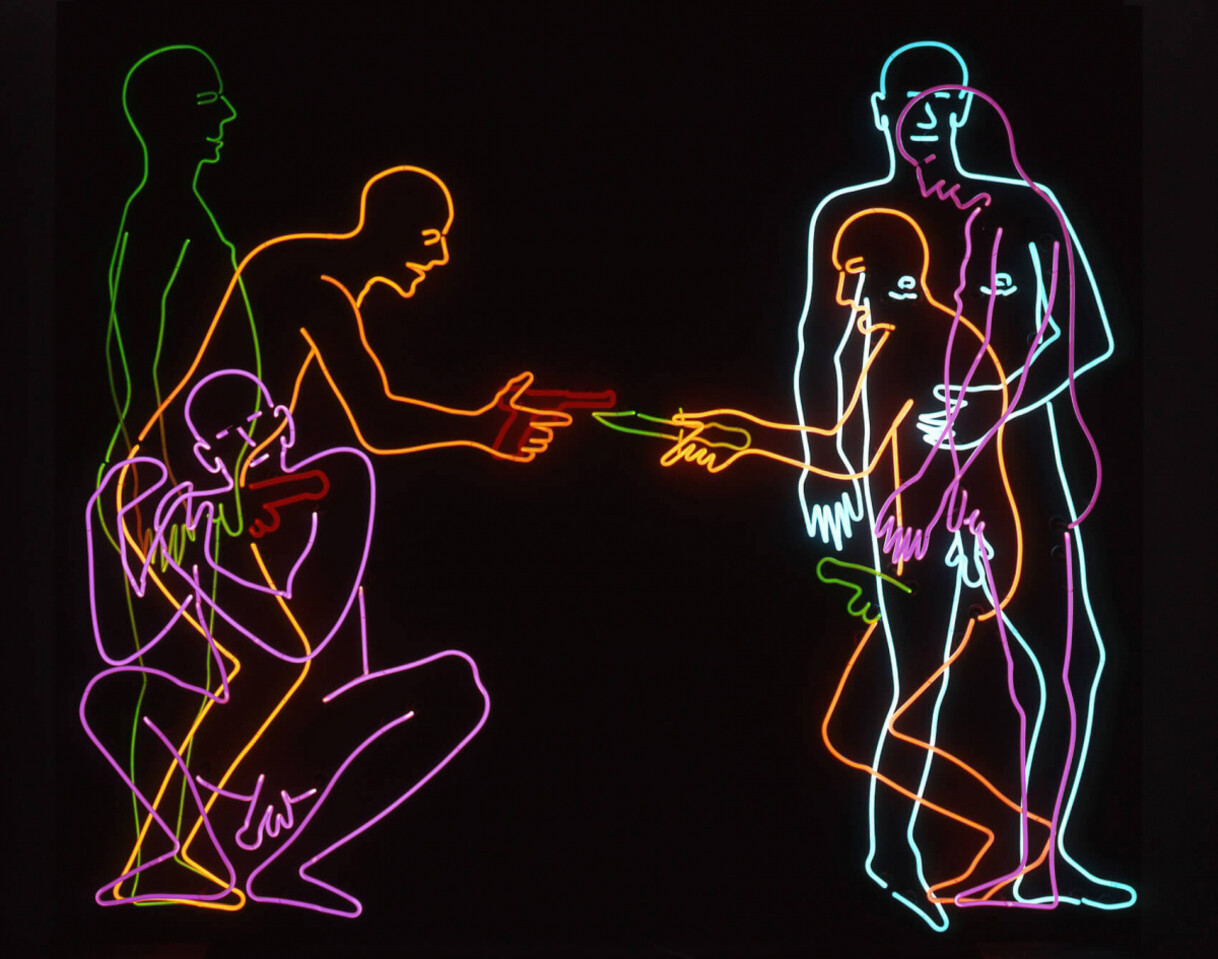

There is something humorous, of course, about Nauman making visible the veiled eroticism of a common custom, but this humour is uneasy, meant to provoke the discomfort that is typical of the artist: his work, like these neon men, alternates between the abject and the aggressive. In another piece from this series, Sex and Death (1985), FIG. 2 male figures (now bald, but still without clothes) lurch between a frenzy of sexualised and violent activities. These include a crouched scene of fellatio, upright figures who look out at the viewer and a more explicitly threatening encounter between two figures facing one another with a red gun and a green knife; the weapons are coordinated to match their red and green erections, equating phallic and deathly power. While their multiple outlines flicker, the superimposition of the figures indicates a stutter in time: it collapses or compresses several distinct bodily postures and temporal moments into one spatial realm.

The proliferation of forms suggests that these figures are not singular (not merely stand-ins for the artist, regardless of his use of a personal template), but represent, metonymically, a much wider aggregate. Given that their contours exactly mirror one another, is Nauman referring to the psychic twinnings, divisions and internal struggles that split all male subjects? Or is he commenting on the hostilities that pervade rigid conventions of masculinity, and by extension patriarchal society? The generic quality of their outlines does not remove them from assumptions about sex or race, but rather exemplifies how a lack of detail or specificity defaults to white masculinity as the presumed ur-body.

The 1985 neon entitled Sex and Death by Murder and Suicide includes what seem to be female forms among its confusing whirl of weapons, hands, tongues, breasts and cocks; but as the bodies rotate through their confrontational sequence, their exact position along the two-sex binary becomes blurred in their pursuit of mutual simultaneous gratification and mutual simultaneous destruction. As is keyed by the title, here the figures also turn their weapons on themselves. In Mean Clown Welcome (1985) – another neon that elaborates on these themes – hands and penises are grossly exaggerated and Nauman’s usually smooth, bland faces have been altered to include round clown noses and crosses for eyes. Instead of being identical doubles, the clown on the left is smiling and the one on the right is frowning, indicating Nauman’s fascination with pairing opposites in order to erode divisions such as good versus bad or viciousness versus entertainment.

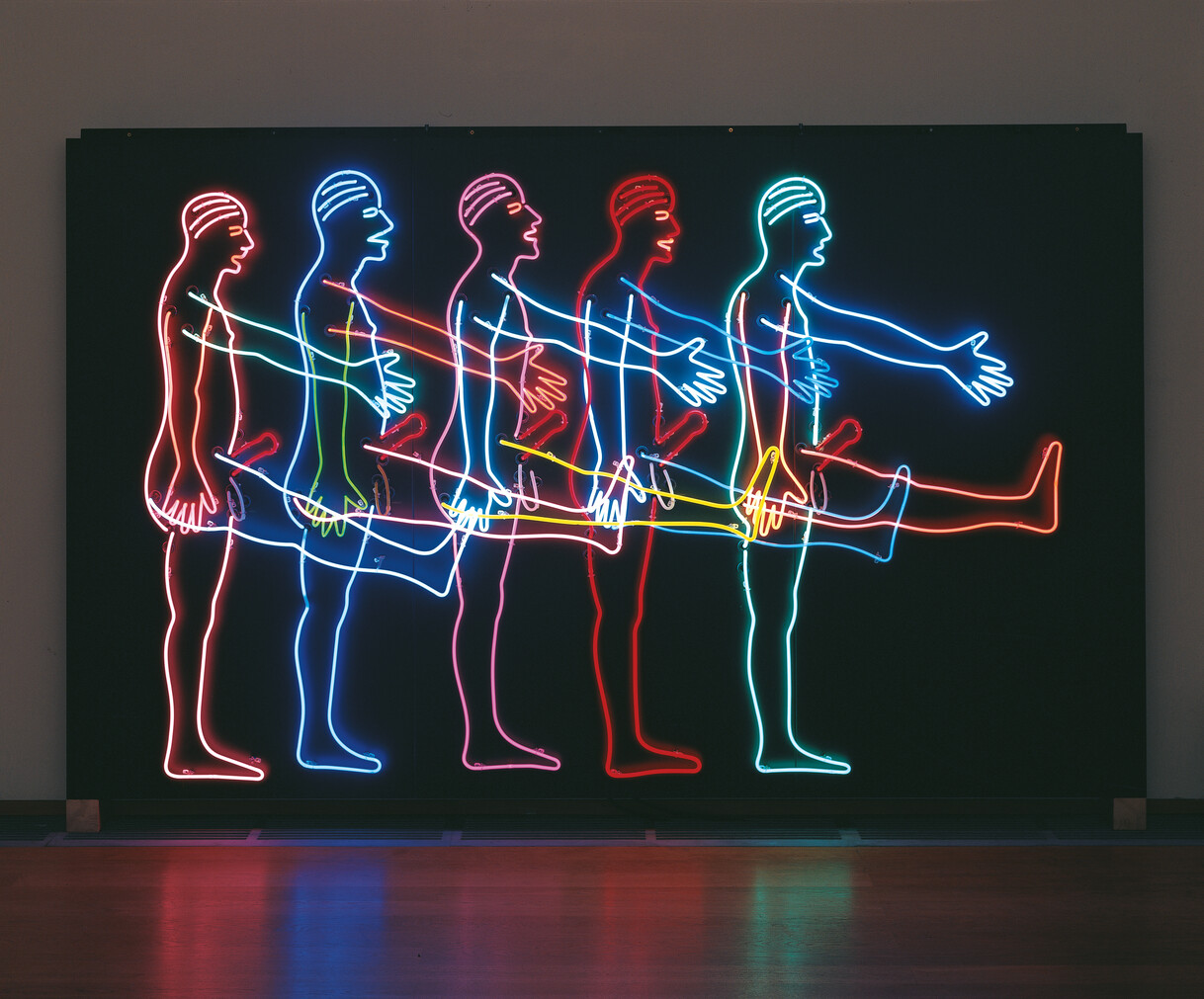

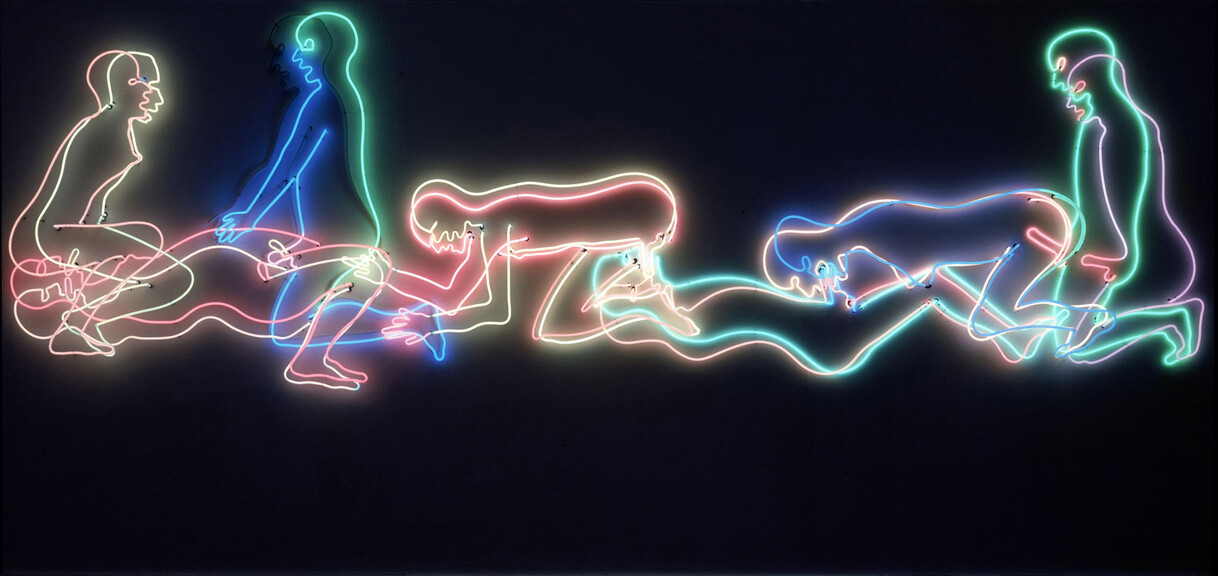

Of the eighteen figurative neons made by Nauman in 1985, twelve depict bodies marked as ‘male’, including Five Marching Men FIG. 3, a parade of goose-stepping conformists whose legs extend so that their feet appear to enter, or anally penetrate, the bodies of the men marching ahead of them. When neons in this series do include female-coded figures, their slippery status as ‘woman’ is usually indicated by a slight swelling of breasts at the chest and a lack of male genitalia.2 In Seven Figures FIG. 4 prone and kneeling figures are arranged in a pornographic chain, with bodies spread out along the wall in an orgiastic configuration of both receptive and penetrative licking, thrusting and intermingling. It is difficult in places to distinguish which organ belongs to which outline, rendering the bodies unstable as sexually fixed or discrete units.

Because of the ambiguity fostered by the overlapping of these silhouettes (the ‘female’ dimensions are not appreciably different from Nauman’s own), many of the ‘women’ enmesh and fuse with the ‘men’, and vice versa. Their sex cannot be fixed, yet because penises dominate this series, the overall impression is that Nauman’s 1985 neon series is overwhelmingly about masculinity. Some viewers barely even detect the ‘women’, such as one critic who writes that the series consists of ‘sexually explicit figurative neons of naked men’.3 The artist’s longstanding focus on failed or impotent masculinity was noted by Pamela M. Lee in an article of 1995, and was described by Catherine Lord as ‘parodic’, ‘panicked’, ‘tortured’ and ‘flatulent’ in her essay that accompanied the 2018–19 retrospective exhibition in Basel and New York.4 As reviews of that exhibition by Ken Okiishi and Jacolby Sattlewhite explore, Nauman has long been riveted by white maleness, as he thematises its capacities to dominate and terrorise as well as its propensities to break down, to fall into ruin.5

Of course, not everyone with a penis identifies as a ‘man’ and not everyone without a penis identifies as a ‘woman’. In these neons Nauman’s indeterminacy, even destabilisation, around genitalia, body parts and their assigned social meaning regarding sex, gender and sexuality, suggests a certain queerness.

Fun from Rear

In fact, Nauman has been playing queer, or playing with queerness, for much of his career. In his Self-Portrait as a Fountain (1966), Nauman re-imagines Marcel Duchamp’s readymade by photographing himself as the urinal. Integral to Duchamp’s joke was the friction generated by the mismatch between object and title – instead of fluid going into the urinal, the name Fountain summons the (possibly alarming, possibly enticing) mental image of fluid coming out. With his narrow bare chest and the arc of water spurting from his mouth, Nauman produces a picture of queer male watersports, a fantasy of doubling and reversal in which he is both receptacle for and source of male excretions. Previous writing on the queer implications of Duchamp’s Fountain, including the gendered choices involved in his selection, framing and documentation of the object, has helped establish that queerness need not only be performed by avowed homosexuals.6

Nauman likewise coyly invokes queerness in his video Walk with Contrapposto (1968) FIG. 5, in which the artist ambulates down a narrow hallway in a fashion that can be described as ‘mincing’, ‘swishing’ or ‘sashaying’. As Nauman evokes classical statuary, he brings it to life through the tilting of his hips in a stereotypically ‘faggy’ comportment. With his arms raised above his head to emphasise his lean, ephebe-esque build, Nauman asserts that queerness might be momentarily inhabited or theatricalised.7 This is a queerness understood not as same-sex orientation towards another – there is no ‘other’ here except the viewer – but as a set of biopolitical habits, corporeal disciplines and physical codes. For pre-Stonewall queer cultures in the United States, these codes were usually enacted only in specific contexts, and were meant to be readable to one’s own communities – a form of communication that emerged from legitimate fears about personal safety.8 Such flamboyant, ‘queenie’ gestures stray from the norm of expected behaviours; when witnessed by antagonistic audiences, they can be despised, policed and punished. Not so in Nauman’s piece, which places him alone in the studio in a slow-motion, solo performance. His burlesque of queer gesture is neither plainly an affectionate homage, nor necessarily charged with contempt.

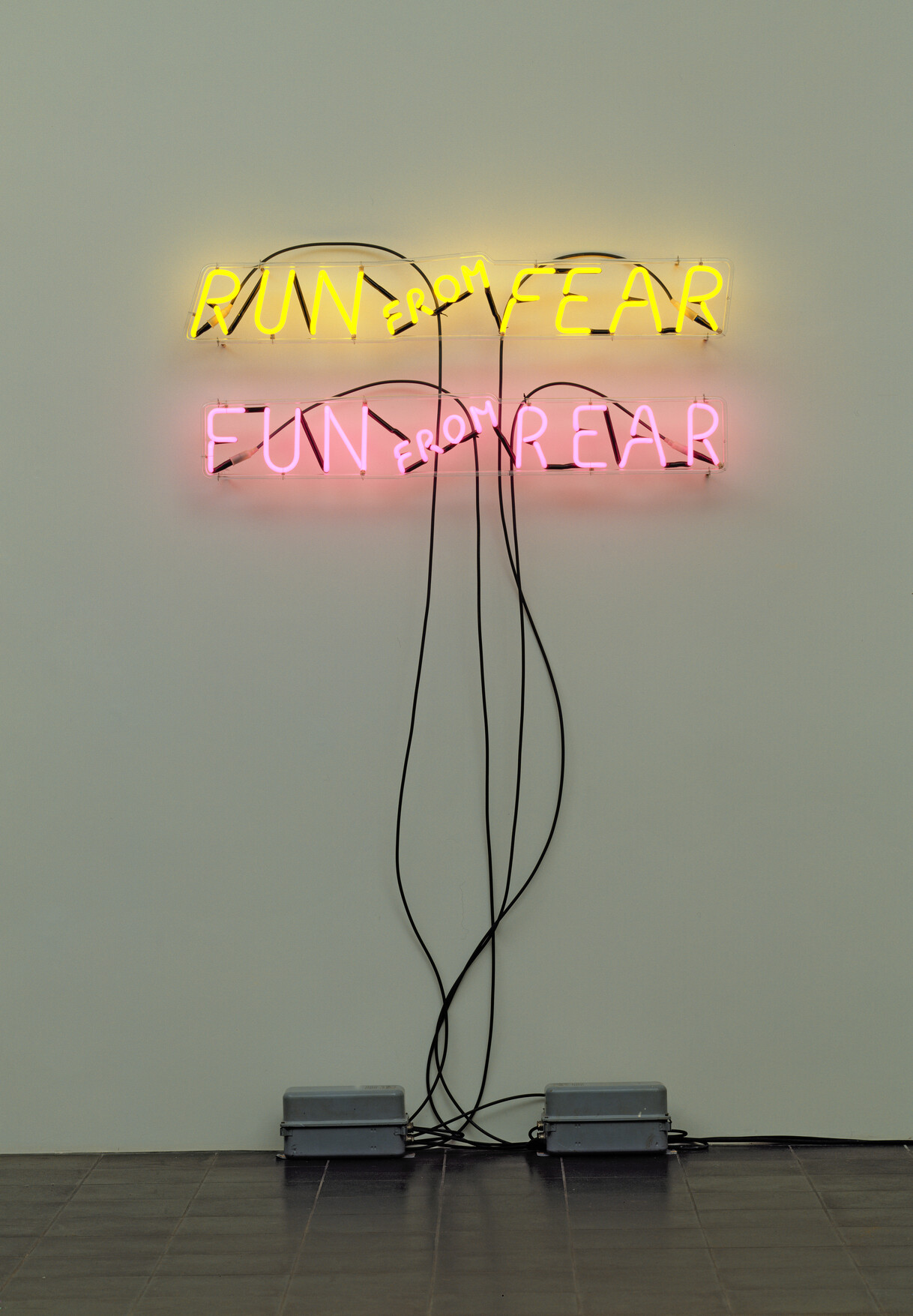

In a text neon of 1972 Nauman further enacts this queer tension by transposing the first letters of the phrase ‘run from fear’ (inspired by a piece of graffiti), transforming it into a winking invocation of anal sex by adding ‘fun from rear’ FIG. 6.9 In six short words he conjoins fright, flight and pleasure, striking an unclear tone: is it fear or fun? Or both? As Janet Kraynak notes, ‘Nauman subjects similar phrases to the babble of repetition by altering letters or using homophonic iterative pairings’.10 Such wordsmithery relies on inversions, anagrams and palindromes, a bi-directional practice of reading that has been termed ‘front/back interplay’.11 Run From Fear/Fun From Rear encapsulates what might be termed, polemically, Nauman’s ‘queer homophobia’, a phrase that suggests an unsettled oscillation between possibly sympathetic embodiment and mocking disavowal that cannot be resolved.

What are the stakes involved in Nauman’s enacting of sexual deviance, as his works by turn own it, practice it and also pathologise it? If Nauman is a theorist of white straight masculinity, he constantly performs the fissures in that configuration – that is, the fractures around whiteness, around straightness and around masculinity. The figurative neons, with their sex and their sadism, are precisely the works where those fissures become most evident and explosive. Just as biography is not relevant to arguments about Nauman’s queerness (he is not gay, but the work can be read queerly), the artist’s personal feelings about homosexuality are not the point – the assertion made here about his queer homophobia is neither an extended ‘outing’ nor a ‘calling out’ of Nauman. It is not an indictment, a dismissal or a diagnosis. It is an attempt to think carefully about his 1985 neon work and its propositions about how (mostly male) bodies move, mean and interact in a specific historical moment.

Disjointedness or Something

Akin to the spouting fountain that might swallow and recirculate intimate liquids, and to the vulnerability summoned in Run From Fear/Fun From Rear, in Nauman’s work not even eyes are safe from violation or invasion. In his Double Poke in the Eye II (1985), schematically rendered hands repeatedly stab at faces, creating a break in the continuous neon tubing at the eye socket, as if the outline of the profile were a membrane or skin that has been ruptured. All orifices and human by-products are up for grabs, including mucus, in Eating Boogers (1985) – one of the sillier and more base depictions of interpenetration in this series – and faeces, in Shit and Die (1985), a phrase that fills the page of an etching.

Although Nauman’s fixations on bodily boundaries are evident across his work, they peak in the early to mid-1980s, as in American Violence (1981–82), which commands the reader to ‘sit on my face’, ‘rub it on your face’ and ‘stick it in your ear’, referring to semen or some other substance, maybe a finger or a penis. In addition to these ambiguities, it is not certain which ‘you’ or ‘my’ is being addressed – these shifting words are contingent upon their readers and the phrases are configured into a shape that recalls, but never quite congeals, into a swastika, evincing Nauman’s persistent conjoining of assaultive Americanness with sexualised physicality. This conjoining has been understood as obliquely critical. ‘Nauman seems to be always slightly political’, writes Peter Plagens, who also calls it an ‘attenuated political art’.12

The artist, for his part, has articulated a vague stance: ‘A lot of the work is about that, frustration and anger in the, with the social situation, not so much out of specific personal incidents but out of the world or mores or any cultural dissatisfaction, or disjointedness or something’.13 The vagueness of Nauman’s politics have been the subject of much debate. Some argue that his articulation of bourgeois alienation and individualism is fundamentally conservative, including Isabel Graw, who in an influential article writes that ‘already in the seventies, Nauman was praised for physically involving the viewer. Yet the body that Nauman involved had neither race, class, nor gender’.14 In more recent scholarship, including a useful volume edited by Eva Ehninger, and the catalogue for the 2018 exhibition, Graw’s claim has been questioned and nuanced.15 One helpful take is proffered by the artist Ralph Lemon, who writes about the seemingly uninterrogated nature of Nauman’s own whiteness, with all the ‘authority, entitlement, youth’ this privilege implies, at the same time that he explains how Nauman’s Wall-Floor Positions (1968) have been a remarkably generative resource for his own work.16

What are the politics of the figurative neons? Medium provides one route to answer this question; Plagens writes that if there is ‘a medium seemingly made for political art, it’s neon. Not only is it the nocturnal language of our turn-of-this-century era, but it’s synonymous – indeed near-identical – with sending an imperative message: buy, eat, see, drink, sleep, save’.17 Yet what is the ‘imperative message’ of the rutting, punching, dying neon figures? The peculiar materiality of this hybrid medium itself – gases (such as neon and argon) are encased in a glass tube and illuminated when charged by an electrical current – is central to Nauman’s project in 1985. Unlike typically straight fluorescent tubes, neon tubing is flexible, accommodating a broad range of curvilinear or angular shapes; it malleably bends to suggest malleable bodies, as well as their luminously leaky borders. Although Nauman’s neon works convey a sense of fabricated, clinical sterility, they are all artisanally produced, with every fragile tube hand-blown. Here another binary is ruptured: manufactured/handcrafted. Given their incredible delicacy, they are frequently created by local neon fabricators near exhibition locations and destroyed afterwards.18

It has been hard for critics to gauge what Nauman is performing or dismantling with this series. Donald Kuspit called the pieces ‘coldly cruel’, writing that Nauman ‘seems homophobic and anti-hedonistic, for all the pseudo-hedonism of his brightly colored neon’.19 Another states, more approvingly: a ‘clown with an erect penis extends his hand to another, who reaches out to receive the greeting, which is withdrawn at the last second. Because they are clowns, this is funny. At the same time, the mean and puerile joke offers a sad commentary on the alienation of people’.20 Who considers these acts of sexual aggression humorous or reacts with a locker-room chuckle? Graw might point out that alienation is insufficient as a politics, and because ‘people’ is an undifferentiated category, the work does not push past being a ‘sad commentary’ into an oppositional stance.

At the same time there are more serious implications to Nauman’s 1985 neons, for his formal propositions are inevitably also political ones. In this series there is little distinction between inside and outside, his or his, hers or hers, theirs or theirs, its or its, yours or mine: which hand belongs where? In Double Slap in the Face FIG. 7, are those splayed fingers on the face or in the face, impossibly engulfed, surrounded by flesh? These are multiplied and fragmented selves, with ever-multiplying digits and forearms and hands that overlap and intersect. Blow jobs, anal sex, poked eyes, eaten boogers: for some these are repulsive, for others, a turn-on. Desire itself is voluble, idiosyncratic, unmappable, uncontainable; it can be as enticing as it is menacing.

Shoot the Queers

Nauman’s neons repeatedly equate sex with death; in Hanged Man (1985), a stick figure with an incongruously fleshy, flaccid penis in the neon’s first state, gets an enormous erection in the second, presumably at the moment of his demise.21 It matters, profoundly, that the artist’s neon-based delve into the human shape – overwhelmingly marked as male, in which sex is irrevocably associated with morbidity – occurred in 1985. 1985 was a watershed moment for both HIV/AIDS awareness and fear of the disease – it was the year that the American President Ronald Reagan first publicly uttered the word ‘AIDS’, the year that Rock Hudson died of AIDS-related causes and the year that the haemophiliac teenager Ryan White was denied entrance to his middle school based on the ignorant belief that his presence would be a threat to other students.22

When does a penis equal a gun or knife (as it does so prominently in Nauman’s neon pieces)? When it can literally kill? Such was the phobic version of AIDS panic widely circulating at that time, in which male-to-male sexual contact was aligned, painfully, with a disease that continues today as a major global pandemic and was then understood to be an automatic death sentence.

In the canon of literature on Nauman, detailed connections between mass-media AIDS awareness and this series of neons are rarely made. In her incisive article Lee situates Nauman alongside artists such as Cary Leibowitz, writing that ‘issues of the failed or abject body are directed towards questions of gender, sexuality, and AIDS’.23 However, another writer, in an attempt to contextualise the appearance of Nauman’s figurative work, states that it is ‘interesting to note that these hints of pictorial pleasures and the reemergence of the figure in Nauman’s work coincide with his meeting in 1985 his future wife, the neo-expressionist painter Susan Rothenberg’.24 This inadequate historicisation, wholly biographical and heterosexual, ignores the prominence of the AIDS epidemic and widespread hysterias around queer sex and death at this moment.

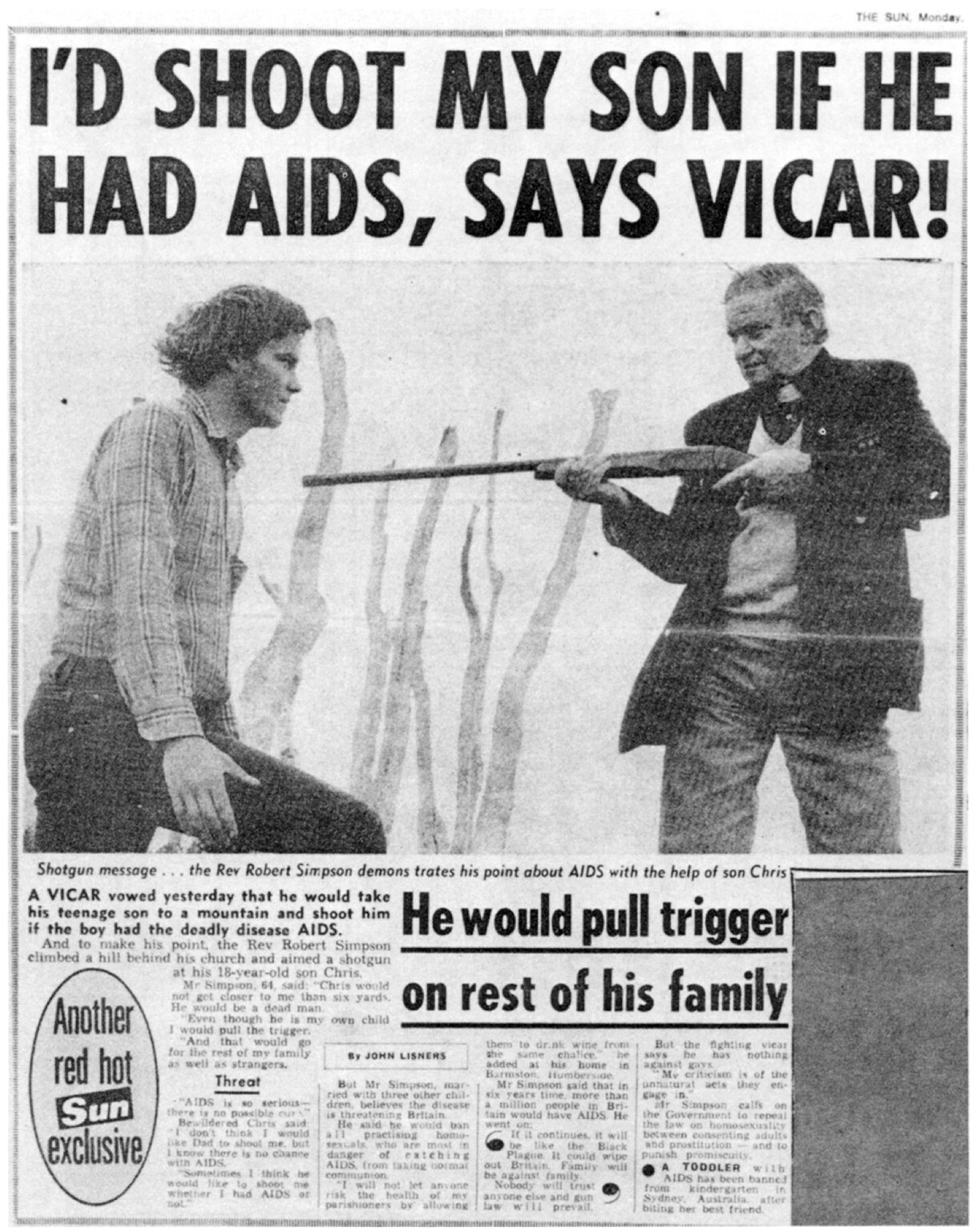

Take, for example, a lurid headline from 1985, published in The Sun newspaper, ‘I’d shoot my son if he had AIDS, says vicar’ FIG. 8. Its accompanying (staged) photograph depicts a man in a clerical collar pointing a rifle at his adult son. This tabloid page was illustrated in Leo Bersani’s article ‘Is the rectum a grave?’, a classic piece of queer theory first published in the 1987 October special issue on AIDS edited by Douglas Crimp.25 Bersani discusses how the AIDS crisis exacerbated imagined connections between penetration and a loss of power, as the promiscuous homosexual male body was demonised as a threat to public health. Bersani does not use the word ‘queer’, because this term had not yet been reclaimed and celebrated, as it soon would be, for its gender-exploding possibilities, both by academics such as Gloria Anzaldúa and activist groups such as Queer Nation (founded 1990).26 Focusing on a pervasive ‘malignant aversion’ to gay male behaviour, Bersani writes that homosexuality must be understood as a historically contingent (and by no means automatically ‘subversive’) subject-position. A tangle of contradictions, queerness ruthlessly enforces its own hierarchies while it is also excluded from ideals of ‘the family’ and ‘the general public’.27 In the face of this uneven political terrain, Bersani points to the Sun article for its inadvertent use of ‘camp’ humour – developed as a survival strategy in the face of struggle – and relishes what he calls a ‘morbid delight’ at its over-the-top ludicrousness.28

Can what one critic calls Nauman’s ‘grim gallows humor’ connect to this campy, queer humour, or are Nauman’s laughs simply a sneering punchline?29 Neons such as Sex and Death, where men suck off and aim weapons at one another, recall how in 1985 Louie Welch (a candidate running for mayoral office in Houston, Texas) quipped, in response to a question about how best to handle the AIDS crisis: ‘one [idea] is to shoot the queers’.30 Welch dismissed his statement as a joke (humour is a ready alibi), and although he ended up losing the mayoral race, he raised a record amount of donations the day after this statement in a burst of approving public support.31

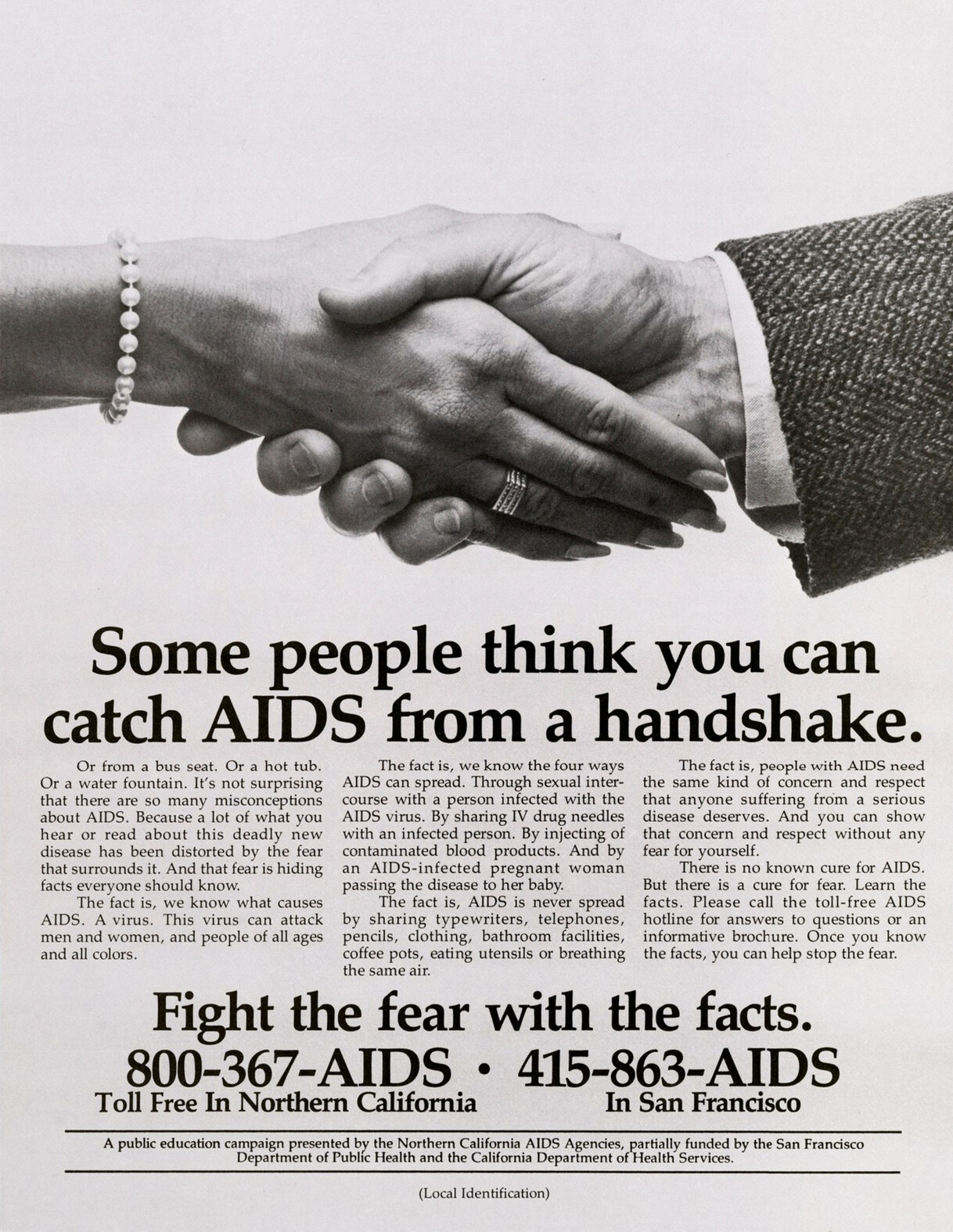

Both Sex and Death and Welcome (Shaking Hands) function as crisp distillations of Nauman’s fixation with queer male-to-male contact in 1985. Even as Welcome (Shaking Hands) functions at a metaphorical level as a comment on masculinist posturing and swagger, it is an unavoidable fact that in 1985 there was widespread misinformation about the nature of transmission of HIV, including panics that such casual touches as shaking hands, hugging or sharing cups might spread the disease. At the same time, massive efforts spearheaded by AIDS activists attempted to assure people their fears were unfounded. An educational poster from the mid-1980s in California makes this point visible: ‘Some people think you can catch AIDS from a handshake’ is written below a photograph of two hands locked in a clasp, with the instruction below to ‘Fight the fear with the facts’ FIG. 9.

A photograph from 1987 of Princess Diana shaking hands, ungloved, with a person with HIV was heralded as a breakthrough moment for AIDS awareness; for some, this was a brave demonstration of compassion through a non-medicalised physical touch. But since there was no actual danger in this contact, the media fascination with (white, rich, straight, ‘pure’) Princess Diana’s alleged ‘courage’ in this moment was nothing but distortion.32 The stigma around shaking hands in 1985 was enormous, and connections between that gesture and potentially deadly male-on-male sexuality were being made across the public sphere – including, ambivalently, in Nauman’s neon pieces.

In addition to their resonance with/against AIDS activist campaigns around touch, Nauman’s neons of 1985 raise issues regarding sound. In the 2018 exhibition catalogue the artist Glenn Ligon, who has also worked with neon, discusses Nauman’s neons in terms of their sonic qualities, connecting the constant hum produced by neon tubing to musical vibrations and rhythms, elaborating upon their ‘immersive acoustic’ qualities.33 Emitting droning sounds as well as ambient light, Nauman’s neons extend past their own boundaries in both space and time to invade ear and eye. Spatially, they are reflected on the floor and create a glow around them on the walls behind them; temporally, they also linger in the viewer’s field of vision, as the neon lights cause a potent afterimage for a moment after the tubes have turned off.34

Although the male bodies in the neons were based on Nauman’s own, and as such evoke his physiognomic whiteness, the neons are actually multicoloured. The figures’ hues – from pale pastels to deep cobalts – range widely, and the technology involved is sensitive enough for some variation to exist even in the same piece when it is re-exhibited.35 White (racially) and not white (chromatically) at the same time, the blues, pinks, greens, reds, oranges and yellows cast themselves onto the viewer’s own clothes and skin as inescapable, temporary stains. To stand in front of these neons is to be enfolded in their glare; they colour the viewer as well as the surrounding architecture. Uncontainable to the limits of the wall, the bodies depicted move from their private acts to contaminate or infect a collective body of witnesses, and serve as a possible reminder of the porousness or inter-relationality of all bodies.

The words ‘infect’ and ‘contaminate’ are used advisedly, for along with the figurative neons, Nauman made a work in the same year that features spiralling text in a format that harks back to his initial neons from the 1960s. Having Fun/ Good Life, Symptoms begins on the left-hand spiral with ‘fever and chills’, then ‘dryness and sweating’, before continuing its list of paired, opposing terms, such as north and south, up and down, in and out. Fever and chills, dryness and sweating are early symptoms of HIV, especially the flu-like seroconversion phase that indicates that a person has contracted the virus. This list of symptoms, seen amid the bodily excesses on florid display in the other 1985 neons, further suggests that Nauman was making these works under the shadow of AIDS and in complex response to its media representations.

Silence = Death

Some evangelical Christians took death by AIDS as the logical, laudable outcome of ‘immoral’ and ‘licentious’ gay sex practices. If 1985 was a pivotal year for mainstream press coverage of HIV/AIDS, so too was it witness to an unprecedented mobilisation of queer communities in the United States and elsewhere, as activists fought to assert that they were not vectors of disease, nor a list of maladies and nor were they willing to be passively depicted as victims or as perverts. Simon Watney understood this moment as the catalyst for a sweeping shift regarding bodily epistemologies: ‘For AIDS is not only a medical crisis on an unparalleled scale, it involves a crisis of representation itself, a crisis over the entire framing of knowledge of the human body and its capacities for sexual pleasure’.36 AIDS activists chose to challenge such knowledge construction using counter-images, text, performance and direct action.

Neon is not only associated with commerce, as Plagens reminds us, with its use in advertising and mercantile signage, it is also evocative of night-time urban cityscapes, of sex work ‘red light’ districts and of the bustle of after-dark activities. It hectors, commanding attention and riveting the gaze. Generating its cloud of colour and its audible buzz, neon has the effect of amplification, both optical and sonic. No wonder, then, that in their window display at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, in 1987, the group of artists collectively known as Let the Record Show… – an affiliate of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) – used neon alongside photographs of and quotes by homophobic public figures, including the Senator Jesse Helms and the conservative writer and thinker William F. Buckley, set against a mural of the Nuremberg trials FIG. 10.37

Hovering above in this display is the neon logo SILENCE = DEATH, rendered in eye-catching pink, white and blue. Closely related to the United States flag colours of red, white and blue, it address the government’s criminal inaction around AIDS. The textual slogan appears under the reoriented pink triangle that would become the signature icon of ACT UP, a resignification of the badge that branded queer prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. In form and content, neon is crucial to how this piece works as a window display and as a political intervention; it functions, to quote Crimp, as a ‘visual demonstration’.38 Unlike Nauman’s neons, which flash on and off and unfold over time – sometimes taking many minutes to spin through their programmed sequences – in the New Museum display, the neon tubes are consistently lit, insistently blaring a message out towards the street. The equal sign in SILENCE = DEATH proposes a definitive causation, producing one response to Bersani’s provocation that, in the face of prejudice and neglect by the government, ‘morally, the only necessary response to all of this is rage’.39

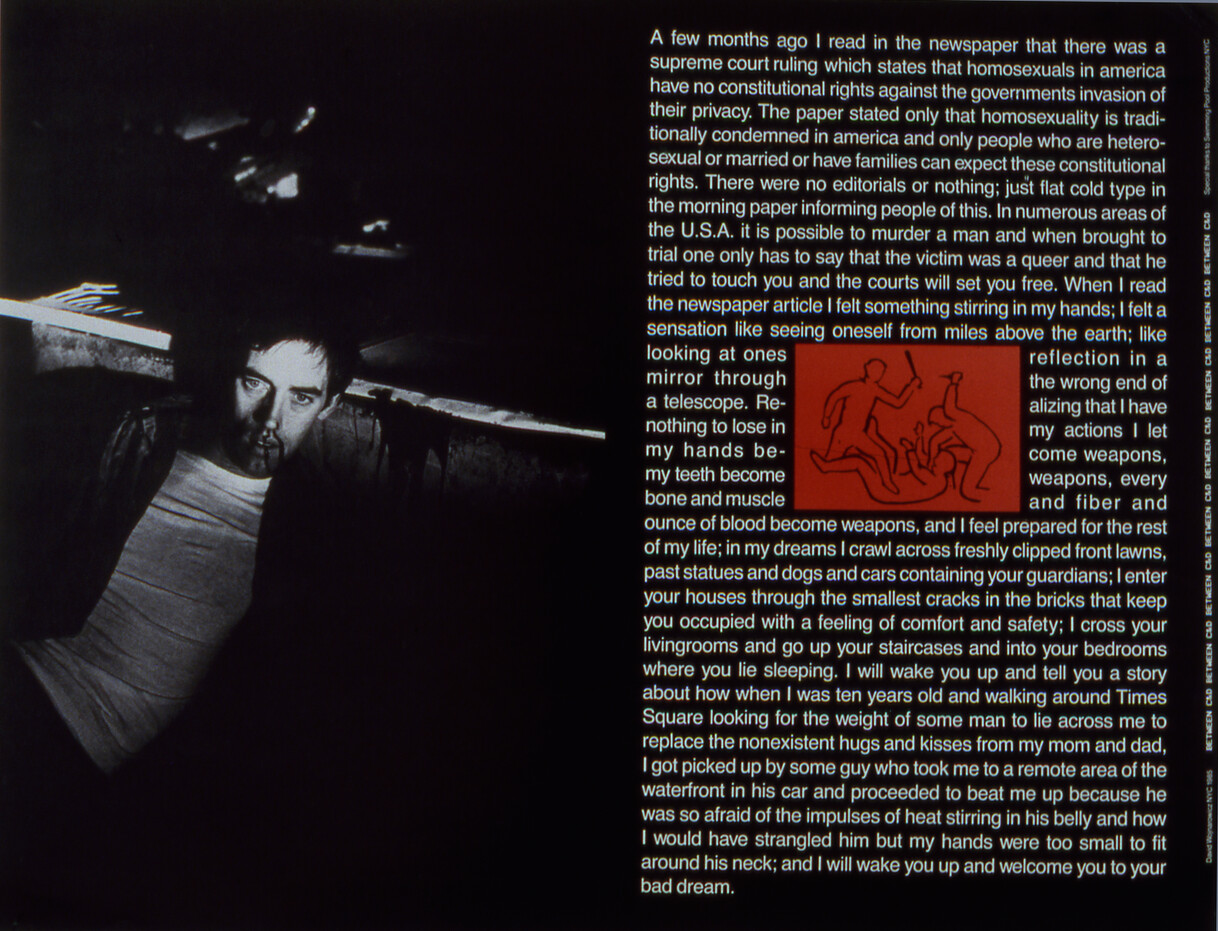

This rage is palpable in many of the responses to the AIDS crisis made by queer male artists working in the mid-1980s. David Wojnarowicz exclaimed that, ‘realizing I have nothing left to lose in my actions I let my hands become weapons, my teeth become weapons, every bone and muscle and fiber and ounce of blood become weapons, and I felt prepared for the rest of my life’.40 His passage proposes weaponising the queer body as a move of self-protection in the face of the then legally outlawed status of queer sex. This text also appears in Wojnarowicz’s print, Untitled Between C & D FIG. 11, a diptych in which a photograph of the artist with a bloodied nose is set next to a dense block of words. Embedded within the text is a small drawn vignette on a crimson field that depicts violent male-on-male physical contact. As with Nauman’s neons, Wojnarowicz leaves the faces featureless and empty, using outlines to let the viewer fill in the blanks. In relation to Wojnarowicz’s excoriating words, the drawing of a beating perpetrated with stick, knife and foot – a ‘gay bashing’ – becomes generic, shorthand for repeated subjugation over time, one of many such incidents have happened and that will happen.41

The outline was also widely deployed by Keith Haring, including in his street art and in his activist graphics. Despite its surface affinity with Nauman’s neons of the same period, Haring’s work tends to speak directly about what goes unstated in Nauman. One work by Haring from 1985 evokes the state’s active suppression of queer desire: a black figure is forcibly having his penis snipped off with a pair of scissors wielded by white hands, punctuated by spurts of bright red blood FIG. 12. This racially loaded scene could be an explicit reference to the racialisation of the AIDS epidemic, one that (then as now) hits black men in disproportionate numbers.42 It also sums up the attitudes of some right-wing politicians and religious figures in the United States who advocated extreme measures, including quarantine (like Helms wanted) or tattooing gay men’s buttocks (as was advocated by Buckley), to stop the spread of AIDS to ‘innocent’ victims.

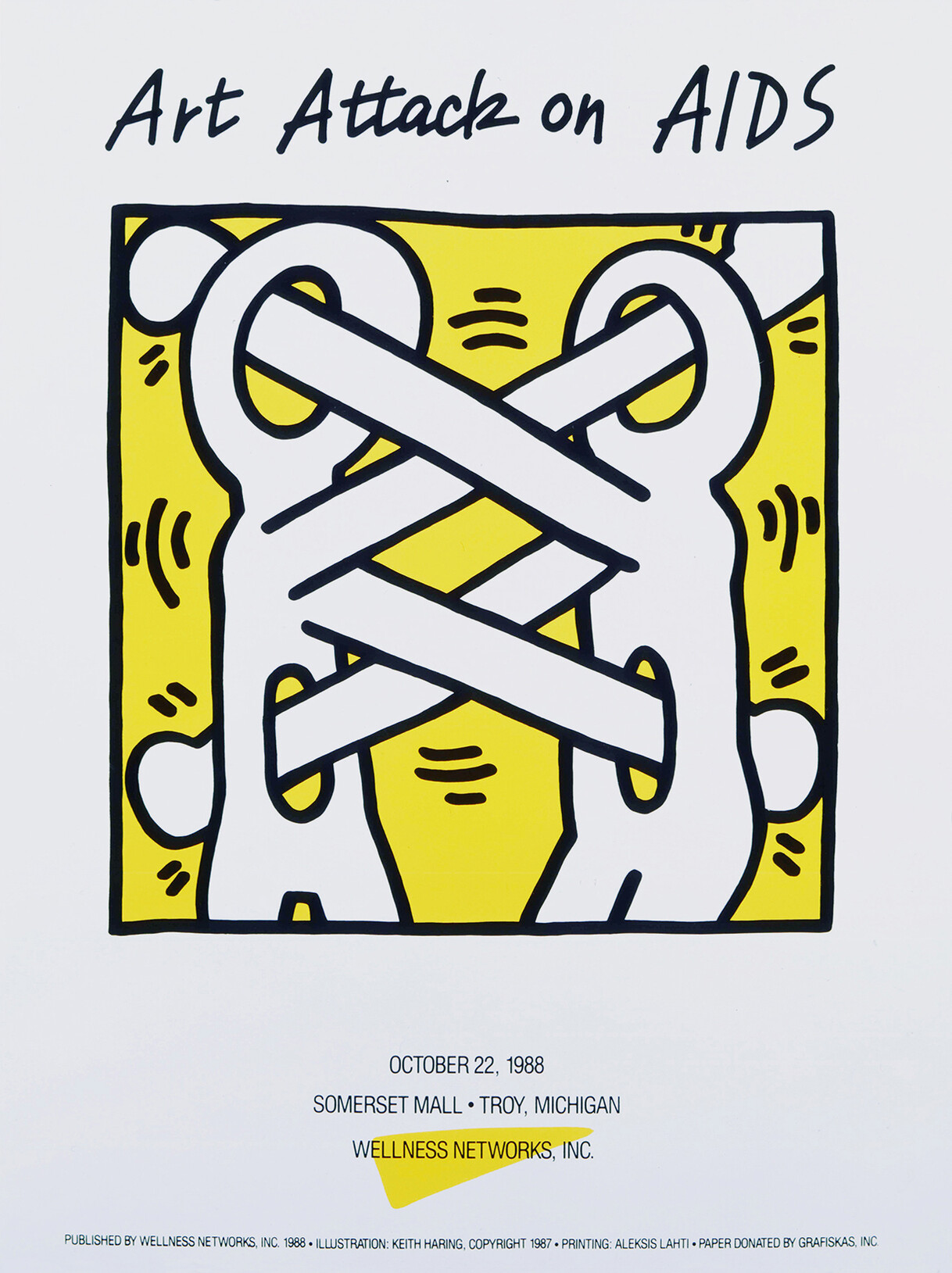

A further similarity between Haring’s work and Nauman’s 1985 neons can be found in the poster Art Attack on AIDS FIG. 13 in which outlined figures become porous and open to each other. In Haring’s rendering, hollow faces and stomachs are punctured by the fists of an opponent; because the bodies are equivalently violated and violating, the blow of impact becomes an intertwined embrace.

Both Wojnarowicz and Haring died of AIDS, in 1992 and 1990 respectively; over the course of the 1980s they had seen friends, collaborators, partners and lovers ravaged by the disease. Although their works are pertinent comparisons for Nauman’s 1985 neons, with their intimations of the AIDS crisis and struggles around the representation of sex, Nauman’s detached tone occupies a separate arena from Wojnarowicz’s and Haring’s legible, combative, political anger. Recent exhibitions that aim to historicise the 1980s have insisted upon the relevance of the pervasive context of AIDS for the art of that decade in the United States;43 this holds true as much for Nauman on his ranch in New Mexico as it does for queer activists in New York, although there are sharp divergences in how these artists’ works look and feel.

Fuck Bruce Nauman

Nauman’s neons from 1985 beg the question: do they accord with the homophobic view of AIDS that cast the disease as the direct result of what Bersani calls ‘insatiable desire [. . .] unstoppable sex’?44 Or do his neons, with their endless copulations without climaxes, participate instead in a radical redefinition of sex, one in which individual personhood merges into an intersubjective entanglement and mutuality – the most thrilling threshold of queer possibility? Or do they exist in some undecidable space between or outside that false binary? Nauman’s figurative neons show bodies full of holes; as mere outline they are almost nothing but hole or blank, and as such could be read as the ultimate genderless horizon. In these works bodies, constantly penetrated from all sides, veer between wielding and relinquishing power, fucking and being fucked, murdering and being murdered.

Nauman’s figurative neons had their debut in 1985, showing at the Donald Young Gallery in Chicago as well as at Leo Castelli in New York, where their rebarbative forms were met with puzzlement. ‘People were surprised’, reported Young, adding that ‘nothing sold at first’.45 In fact, according to an account from 1990 of Nauman’s ascension to art market star status, not a single figurative neon was purchased for a full year, until Charles Saatchi bought one in 1986, for $40,000–50,000.46 Since that time, their value has increased by at least tenfold; the editioned Double Poke in the Eye II (1985) – a version of which, significantly, was exhibited in the benefit group show Art Against AIDS at Leo Castelli in 1987 – sold in 2015 for more than $500,000.47

The 1985 neons flicker through programmed sequences that illuminate various sections procedurally, moving through a limited set of options that endlessly repeat. Ute Holl calls them ‘moving pictures’, and discusses their most explicit precedent, the ferociously farcical puppet show Punch and Judy.48 Nauman himself says: ‘With the figure neons, the timing sequence is very important – it becomes violent. The pace and repetition make it hard to see the figures, and although the figures are literally engaged in violent acts, the colors are pretty – so the confusion and dichotomy of what is going on are important’.49 In this quote Nauman provides some crucial terms, namely, difficulty (‘hard to see’) and confusion. The difficulty and confusion around the dichotomies that he describes (pretty colours set against violent subject-matter) can be extended to the other dichotomies at issue in this series: male/female; mastery/subordination; whiteness/non-whiteness; and queerness/homophobia.

Indeed, the flickering of the neons does not just align them with cinematic or time-based performance. Such flickering is also an ideological operation of oscillation fundamental to Nauman’s project in 1985: these irreconcilable positions cannot be held still. They are simultaneously queer and homophobic – they change from one to the other in a flash, forever alternating between postures. Bersani argues that the unfettered promises offered by homosexuality lie at the heart of homophobia and that homophobia can be inextricably present (he calls it an ‘uncontrollable identification’) within queerness; Nauman’s neons visualise this co-constitution.50

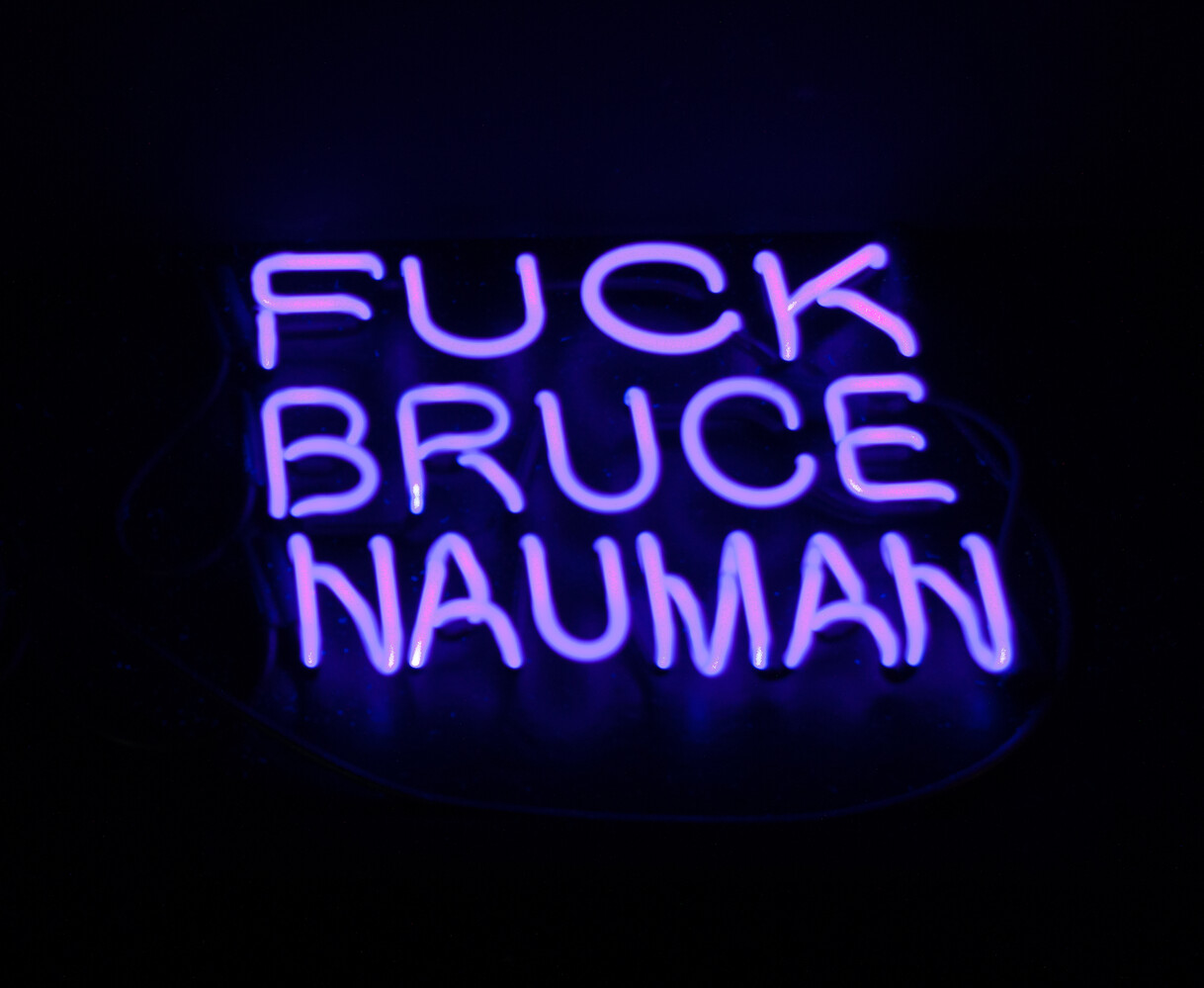

The structural ambivalence that is at the core of Nauman’s neons generates, in turn, its own ambivalence, one articulated by Ralph Lemon in his 2015 Black Light Neon: ‘FUCK BRUCE NAUMAN’, writ in black neon FIG. 14.51 As in, you might want to fuck him (in his catalogue essay, Lemon calls Nauman ‘sexy, sexual but not fey’), but also, fuck him.52 Acknowledging Nauman’s ‘ownership’ of neon and expressing reservations about his uncontested straight white male liberties, Lemon’s blunt yet open-ended statement encapsulates how longing can flip to loathing – no less than queerness can twist out of homophobia – in the blink of an eye.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to Isabel Friedli for her initial invitation, Thomas Lax and Will Rawls for their encouragement, Ralph Lemon for his kind permission, Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen for her writerly camaraderie, and Mel Y. Chen for everything everything everything. This article is dedicated to Jon Raymond, in honour of twenty-five years of our thinking about Nauman together.