This is an edited excerpt from the foreword to the English translation of Domenico Quaranta’s book ‘Surfing with Satoshi: Art, Blockchain and NFTs’, published by Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, in May 2022.

I wrote the very last words of Surfing con Satoshi on 4th May 2021. The deal with the publisher was to have it out in about a month, and we did. At the time, I was well aware of the risks of putting ink on paper about art, blockchain and NFTs. In the introduction, I wrote: ‘At best, the result will be bibliographically obsolete within a few months. At worst, it will fail to include developments and issues that have become crucial in the short time between the “imprimatur” and the market’. This turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Almost a year later, when I started working on the English translation, the big question was how to deal with the question of obsolescence. Then I read the book and, to my surprise, I realised that though it had of course aged, it had aged pretty well. Things have happened since May 2021, some on a scale that would have been difficult to predict, and other things are happening as I write these pages. Yet none of these developments have significantly changed the overall picture. Rereading the book, I was sometimes tempted to add in new references, new examples, new facts and figures, but I never felt the need to reroute the flow of arguments, or change my conclusions.

I am not going to claim the merit for this. On one hand, it is because Surfing with Satoshi is not entirely bound up in the extreme present, as much as it might appear to be, even to its author. It starts with a simple, straightforward introduction to the history, ideologies and technicalities of blockchains and cryptocurrencies, the relatively short tradition of blockchain-related art, and the concepts of authenticity, originality, scarcity and dematerialisation deeply rooted in Western culture and contemporary art. All of this could of course be improved and updated, or even reframed by new studies and insights, but it is not rendered obsolete by current affairs. On the other hand, it is because the seeds of all the developments that have come about in this last year had already been planted, hidden in plain sight.

Everything that has happened since March 2021, when Beeple’s Everydays was auctioned by Christie’s for the exorbitant figure of $69 million, has been the predictable outcome of a business scaling up, of an experimental solution formerly relegated to a niche culture being adopted by the mainstream. I dare say it could have been predicted long before May 2021. If you want a proof of concept, I would invite you to read an old essay that hasn’t aged a bit: Martin Zeilinger’s ‘Digital art as “monetised graphics”: enforcing intellectual property on the blockchain’, written in 2016 and published in 2018. At a very early stage of the NFT ‘revolution’, Zeilinger intuits the role art should be playing in this context, stating that it has to act as a ‘zone of resistance’, rather than becoming an ‘embattled target of commodification and financialisation efforts’.1 He also realises something that recent developments have widely evidenced, namely that, setting aside any techno-determinism, blockchains themselves are not changing the world – they can only adapt to, reproduce and possibly exacerbate, the present system’s structure and ways of working. As Zeilinger writes about the promise of decentralisation:

Once decentralisation technologies are folded into proprietary, commercial products and services, models of centralised finance will be far from being disrupted but rather reinforced. The fact that such technologies are cryptographically secure might simply mean that the centralisation efforts they ultimately represent will be difficult, if not impossible, to counteract.2

This changed everything

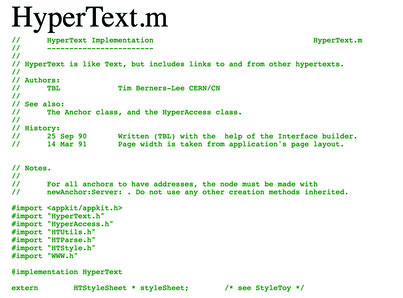

In June 2021, Sotheby’s auctioned the original source code of the World Wide Web, made available by none other than the inventor of the Web himself, Sir Tim Berners-Lee FIG.1.3 This event – titled This Changed Everything – deserves a place in history not because, as some have said, Berners-Lee sold the Web – he didn’t. As he pointed out, ‘the web is just as free and just as open as it always was. The core codes and protocols on the web are royalty free, just as they always have been’.4 What he sold was a graphic rendition of the original code, ‘a picture that I made, with a Python programme that I wrote myself, of what the source code would look like if it was stuck on the wall and signed by me’. It did not even fetch a historic sum, although some may argue that $5.4 million is quite a lot for a signed, certified, unique poster accompanied by an animated visualisation and a letter (all the proceeds of the sale benefited various initiatives that he and his wife, Rosemary Leith, support). This event made history on a symbolic level, because of the way it puts Web3 rhetoric into practice and legitimises it, and also what Berners-Lee said about it: ‘NFTs, be they artworks or a digital artefact like this, are the latest playful creations in this realm, and the most appropriate means of ownership that exists. They are the ideal way to package the origins behind the web’.

Berners-Lee is not your average tech inventor, trying to monetise his game-changing technology any which way. After releasing the original code for the Web, his life became a mission, and an ongoing struggle, to keep its standards open and free, effectively pursued with the help of the W3C Consortium. His endorsement of NFTs as ‘the most appropriate means of ownership that exists’ came at a time when the crypto bros and NFT platform founders were working hard to stress the lineage between the early, decentralised internet – open, democratic, anonymous – and the so-called Web3,5 in opposition to evil Web 2.0, with its centralised structure, surveillance, harvesting and exploitation of user data.6 Consciously or not, by auctioning the original code of the Web as an NFT, its inventor is saying: this is the way the open environment I envisioned in the early 1990s will evolve in the future.

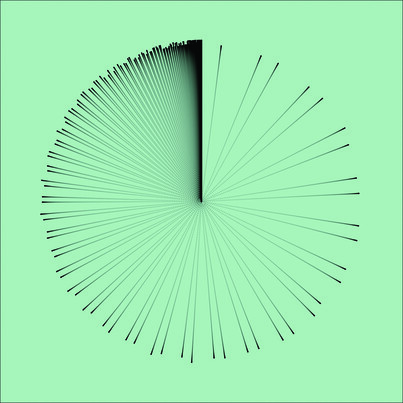

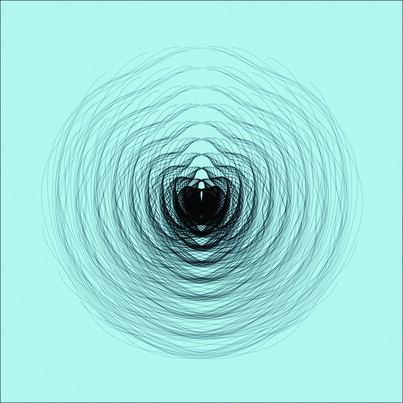

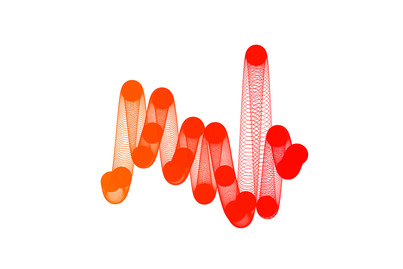

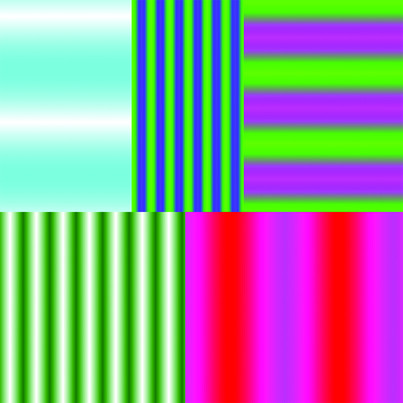

Yet there is much criticism of this utopian vision of Web3. Moxie Marlinspike’s long essay7 of January 2022 provides an in-depth technical analysis of the infrastructure of Web3, and earned a response from Vitalik Buterin, the co-founder of the Ethereum blockchain.8 According to Marlinspike, even if blockchains are decentralised, the infrastructure of the dApps (decentralised apps), platforms and services that are built on them is not. Why put so much effort into forging a trustless, distributed consensus mechanism, when to access it we still have to rely on a traditional, server-based structure and a few centralised platforms we are forced to place our trust in? Why spend so much money and energy to secure an NFT, when anyone can ‘change the image, title, description, etc. for the NFT to whatever they’d like at any time (regardless of whether or not they “own” the token)’? Marlinspike illustrates his points by producing some interesting projects on the Ethereum blockchain. In At my whim FIG.2 FIG.3 FIG.4, he shows how the same NFT can be linked to different digital contents depending on where and how it is visualised: on OpenSea his content looks like an abstract digital drawing, on Rarible it presents as a different abstract graphic, but when you buy it and view it from your crypto wallet, it displays as a large 💩. Marlinspike concludes: ‘Once a distributed ecosystem centralizes around a platform for convenience, it becomes the worst of both worlds: centralized control, but still distributed enough to become mired in time’. If this trend doesn’t change, Web3 is cursed to evolve into ‘Web2x2 (Web2 but with even less privacy)’.

Generative codes on the blockchain

A similar turning point came in August 2021, when a relatively young, little-known NFT platform made profits on an unprecedented scale, $626 million in a month. The brainchild of the entrepreneur and programmer Eric Calderon, Art Blocks launched in November 2020 with Chromie Squiggle FIG.5, a project by Calderon himself (under the moniker of Snowfro) which illustrates the potential of the platform, and is described as his ‘personal signature as an artist, developer, and tinkerer’.9 Instead of uploading a static or animated file on a platform and minting the associated NFT, Calderon designed a system that enables users to deploy a generative code directly on the blockchain. As the platform’s ‘learn’ page explains:

A generative script (using p5js for example) is stored immutably on the Ethereum blockchain for each project. When a user wants to purchase an iteration of a project hosted on the platform, they purchase an ERC721 compliant ‘non-fungible’ token, also stored on the Ethereum blockchain, containing a provably unique ‘seed’ which controls variables in the generative script. These variables, in turn, control the way the output looks and operates.10

The smart contract associated with each project also determines the number of ‘seeds’ that can be generated. Usually it is a large ‘edition’ of unique variations: for Chromie Squiggle, and many other projects presented on Art Blocks, this amounts to ten thousand mintable pieces. When a new project is launched on the platform, new pieces are generated on request and minted directly by the collectors who participate in the auction. When all the seeds have been sold, the minting process stops, and from then on the individual works are only available on the secondary market.

In other words, instead of allowing artists to upload static or animated images available for purchase as unique pieces or limited editions, Art Blocks exploits the programmable nature of blockchains to share dynamic codes that can generate hundreds or thousands of unique items on request; its economy is based not on selling individual expensive digital works of art to wealthy crypto collectors, but on the involvement of a broader community of generative art enthusiasts, who can mint and own a unique piece for a relatively small amount of money. And if the project is successful, the value can grow. By way of example, on 30th July 2021, the Dutch artist Rafaël Rozendaal dropped the project Endless Nameless FIG.6 on Art Blocks. The piece consisted of one thousand mintable items, generated by a code described as an ‘exploration of composition’, which produced colourful animations based on ever-changing arrangements of RGB colours and square shapes.11 The starting price was set at 0.25 ETH, and a ‘split’ was programmed to award fifty per cent of the proceeds from the primary sale to the non-profit organisation Rhizome. The project sold out pretty fast, and on 5th August Rhizome announced that it had brought them more than 164 ETH: then worth around $430,000, this was ‘the largest benefit donation in Rhizome’s twenty-five-year history’.12

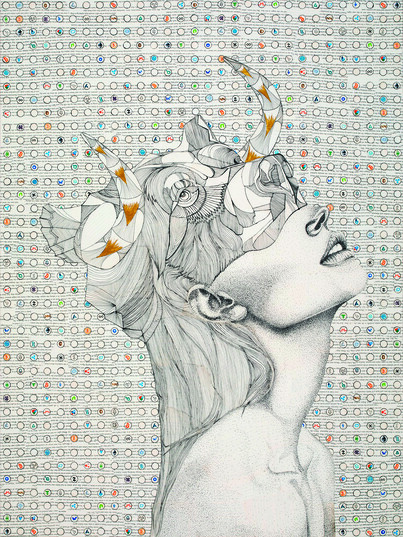

One unexpected outcome of Art Blocks’s success is that it has not only changed the visual landscape of NFT art, but has also, for the first time, significantly affected the tip of the pyramid of the best-selling NFT artists. Generative processes have been used in art since the early days of Computer Art in the 1960s and 1970s, and many practitioners have acknowledged the notion’s influence on various trends, including geometric abstraction, conceptual art, process-based art and minimalism. Although the field is as rich and diverse as always, including engineers, designers and amateurs, generative practices also have been adopted by many visual artists with a strong reputation in the contemporary art field, from Casey Reas to LIA, from Harm Van Den Dorpel to John F. Simon Jr. to Rozendaal himself. Thanks to the model launched by Art Blocks, and rapidly followed by other platforms, thousands of generative graphics have flooded the blockchain, undermining the dominance of pop-surreal aesthetics, pixel art and memetic imagery.

The way in which Art Blocks affected the world of NFTs soon became visible in the market too. In May and June 2021, both Sotheby’s and Christie’s offered curated auctions which aimed to bring together the rising stars of the NFT environment and established media artists. Christie’s Proof of Sovereignty13 featured Nam June Paik, Jenny Holzer and Urs Fisher along with emerging ‘crypto artists’, such as Raf Grassetti and Josie Bellini. Similarly, Sotheby’s Natively Digital14 auction included works of art by Casey Reas, Ryoji Ikeda, Simon Denny and Addie Wagenknecht, along with pieces by ‘crypto art stars’, such as Pak, Don Diablo, Fvckrender, Xcopy and Larva Labs. Both auctions accepted crypto for payments, and were of course swarming with crypto collectors. And the latter’s protégés ended up stealing the show, while the works by ‘artworld artists’ did not significantly outperform their primary market quotations. Christie’s auctioned a scan of a manual drawing and collage by Josie Bellini FIG.7 for $400,000, while a clip from Paik’s video Global Groove (1973) regrettably sold for just $56,250, half the lower estimate. At Sotheby’s, Larva Labs’s CryptoPunk 7523 FIG.8 got sold by a collector named Sillytuna for more than $11 million, while Ikeda’s work only fetched $76,600. The only real revelation was Kevin McCoy’s Quantum (2014), which sold for $1,472,000, as the NFT world cottoned on to the fact that it was in the presence of the first ever NFT. The crypto whales were still shaping their own art world, in their own image and likeness.

This approach to collecting hasn’t completely changed, but a quick look at the list of the most successful artists at the beginning of 2022 provides a very different snapshot of the NFT scene. Young generative artists who have made a name for themselves on Art Blocks, such as Tyler Hobbs FIG.9 and Dmitri Cherniak, are now tailing Pak and Beeple, and overtaking XCOPY, Hackatao and FEWOCiOUS, to mention a few of the artists discussed in this book. Casey Reas has made around $12 million so far, and Rozendaal more than $6 million.

The Left can’t crypto

In December 2021, the media theorist and journalist Evgeny Morozov, together with the non-profit CAII (The Center for the Advancement of Infrastructural Imagination), launched The Crypto Syllabus, a blog that publishes unusually long, in-depth interviews with many critics of the crypto space. Explaining the mission of the magazine, Morozov writes:

The debate on crypto-related topics has been dominated, almost exclusively, by a very tight coterie of voices. The critics of crypto have not done this field a service by being excessively dismissive and polemical; it won’t suffice to dismiss it as mere fraud or a bubble… However, it’s the true believers that worry us the most. In today’s bizarre world, the main organic intellectuals of the crypto sphere are the venture capitalists, who, in the absence of an active pushback from progressive circles, have established themselves as the voice of common sense on all things digital.15

Morozov is not alone in noticing that, in the face of the aggressive rhetoric of crypto entrepreneurs, progressive thinkers have often barricaded themselves into positions of criticism and dismissal. As the writer Daniel Pinchbeck puts it in his newsletter: ‘For the most part, the traditional Left passionately despises crypto and its latest innovations’.16 Critical voices have been multiplying in recent months (thanks also to The Crypto Syllabus), from philosopher Slavoj Zizek17 to art theorist Marina Gržinić,18 from the artists Geraldine Juárez19 and Aram Bartholl20 to the Creative Technologist Martin O’Leary,21 from blogger Tante22 to the media theorists Felix Stalder23 and Ian Bogost.24 In some of these texts, the idea that the only possible way to deal with crypto is to stay out of it altogether is clearly stated. ‘I don’t have any kind of counter-paradigm or ‘proposal’ against NFTs specifically: I’m more inclined to do nothing about it, to refuse participation in the process of capitalisation, and simply not add more blocks to the chains’, Juárez says in an interview. ‘The promotion of cryptocurrencies is at best irresponsible, an advertisement for an unregulated casino. At worst it is an environmental disaster, a predatory pyramid scheme, and a commitment to an ideology of greed and distrust. I believe the only ethical response is to reject it in all its forms’, Martin O’Leary writes in his text.

Many critiques of the crypto ideology point to its origins in crypto anarchism and techno-libertarianism, harking back to the Austrian school of economics and its belief that the only way to achieve political and moral freedom is to give individuals full economic freedom. It is fairly easy to point out the right-wing, sometimes even fascist, implications of crypto anarchism, above all in the theories of Timothy C. May, the author of ‘The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto’ (1988) and ‘The Cyphernomicon’ (1994), and those of Nick Szabo, the inventor of smart contracts. Both take a stand against state power and welfare politics, defend privacy and individual greed, and make some explicitly anti-democratic statements. At oft-quoted point 6.7.3 of ‘The Cyphernomicon’, May writes: ‘Crypto anarchy means prosperity for those who can grab it, those competent enough to have something of value to offer for sale; the clueless 95% will suffer, but that is only just’.25

What is less obvious is how progressive thinkers, programmers and activists have contributed to developing cryptographic technologies and the ideas behind them to improve democracy and question capitalism, rather than destroying the former and turbo-accelerating the latter, as those mentioned above seem intent on doing. In 1991, Philip Zimmermann, the inventor of PGP (‘pretty good privacy’, the encryption system we are still using to authenticate and protect online communications), wrote:

If we do nothing, new technologies will give the government new automatic surveillance capabilities that Stalin could never have dreamed of. The only way to hold the line on privacy in the information age is strong cryptography [...] When use of strong cryptography becomes popular, it’s harder for the government to criminalize it. Therefore, using PGP is good for preserving democracy. If privacy is outlawed, only outlaws will have privacy.26

In April 2011, the free software coder and activist Denis ‘Jaromil’ Roio wrote a short text that became popular as ‘The Bitcoin Manifesto’, in which he claims:

this is now the end of the *flow capitalism*, which consists of the monopoly on transactions, the hegemony of banks on the movement of values and not just their storage, this middle-man mafia strangling the world as we speak [...] the death of the flow capital is a new stage for the necrotization of capitalism.27

Jaromil is also the author of the longer paper ‘Bitcoin, the End of the Taboo on Money’ (2013), later included in his PHD thesis on algorithmic sovereignty. In the paper, cryptocurrencies are described as the outcome of a participative process, and a commons, capable of reversing the way in which, for centuries, money has been the result of a process of accumulation based on violence and authoritarian power. ‘Bitcoin makes it possible for money to become a common and no longer a top-down convention imposed by a sovereign and its liturgy of power’, he writes, adding:

Being involved in the community that has grown around Bitcoin I can see that the community is comprised primarily of young idealists rebelling against the status-quo, especially when it consists of a centralized administration prone to corruption. It is clear to many how unjust monopolies are often dominating various contexts, curbing the possibilities of innovation that are in the hands of younger generations. The liberation of the medium of value exchange is an act we refer to as ‘breaking the Taboo on Money’. Bitcoin has a role in history: its epos coalesces in communities, new ethical reflections, new tales of passion, the glory in all the mystery around its origins. The will for liberation, decentralization and disintermediation is central to Bitcoin – it is ethical and should not be seen as more conflictual than the concrete need to disintermediate many of the systemic functions that are governing modern society.28

‘The left can’t meme’ is a popular saying on the internet, especially in alt-right circles, ‘typically used to criticize the political memes created by left-leaning internet users as unfunny or cringeworthy’.29 With a few exceptions, the Left seem to have developed a similar attitude toward crypto, apparently unable to understand the role that its critical contribution might have in the crypto space, were it constructive rather than dismissive. Daniel Pinchbeck writes:

While challenging the fiat system with a vision of technologically mediated and theoretically depoliticized private money, Bitcoin and the other cryptocurrencies remain tools explicitly designed to perpetuate our current socioeconomic model in which atomized individuals compete against each other for resources, some of which are actually scarce and some of which are kept artificially scarce. The prospect that we might intentionally design and deploy some kind of blockchain-based substitute for the current monetary system to make a world that is more cooperative and regenerative may be very faint, but it cannot be dismissed out of hand.30

This paragraph opens with a quote from the economist, writer and former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, interviewed by Morozov. Taken out of context and at a cursory glance, his statement could easily be interpreted as an outright condemnation of the crypto economy, but this is not the case. In line with how Marx and Engels viewed technology, Varoufakis acknowledges ‘the genuine ingenuity of blockchain’ and its emancipatory potential, but he also believes that no technology alone can emancipate us. ‘Indeed, any digital service, currency, or good that is built on it within the present system will simply reproduce the present system’s legitimacy’. In the past, ‘liberation required a political movement that first overthrows the bourgeoisie and only then presses these magnificent technologies into the service of the many’. And now, ‘blockchain will be useful in societies liberated from the patterned extractive power of the few’.31

The Byzantine Generals Problem

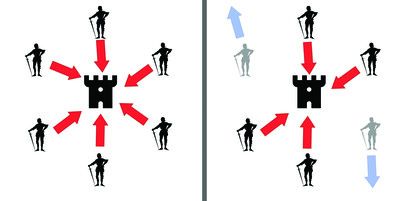

Several generals are besieging Byzantium. They have surrounded the city, but together they must decide whether to attack, and when. Some generals might prefer to attack, others to retreat: whatever they decide, an agreement has to be reached, as a half-hearted attack by a few generals would be worse than either a coordinated attack or a coordinated retreat. The generals are isolated, and there isn’t a secure communication channel they can rely on. Some generals might not even be on side. They can only send their votes via messengers who might not deliver them, or might forge them; some messages might get intercepted, or have been formulated by the opposing side. How can the generals agree to attack or retreat all together, at the same time?

The Byzantine Generals Problem FIG.10 is a game theory problem, an analogy for ‘the difficulty decentralized parties have in arriving at consensus without relying on a trusted central party’.32 The Byzantine Generals Problem doesn’t affect centralised systems: if the generals were coordinated by an emperor or king, a trusted, central authority would be responsible for sending the messages and providing correct information. Centralised systems sacrifice trustlessness for efficiency, and can only be corrupted by the central authority. Decentralised systems, on the other end, require that truth and consensus be established trustlessly.

Blockchains solve the Byzantine Generals Problem in a secure, reliable way, and make cryptocurrencies a revolution in the centuries-long history of money. What really appeals to me about the analogy, however, is the role played by the generals who disagree. If all the generals agreed on the same solution, operating like a hive mind, there wouldn’t be so great a need for a secure, strong, tamper-proof communication system. The system has to be strong and reliable because in a democratic, horizontal society, consensus is arguably difficult to reach. Coming up with a solution that makes everybody happy, with a shared truth, requires time, energy, negotiation. In this process, the dissenters, the critical voices, are much more important than the dependable generals, because they make the group stronger, and the infrastructures it relies on more robust.

As the planets suggest, 2022 might see us entering the phase of cultural absorption and widespread adoption of blockchain technologies, but consensus about them has not yet been reached. This is definitely a good thing: it means that what Morozov calls ‘common sense’ has not yet prevailed, and that the system can still be enhanced and improved. It also means that, now more than ever, critical voices need to step up and make their presence felt. It is my hope that, by questioning technological values (Tina Rivers Ryan),33 and acting as a ‘zone of resistance’ (Martin Zeilinger),34 art and art professionals will take advantage of the central role that the crypto space has granted them to remedy its present snafus and help determine its future developments.

Footnotes

- The full quote: ‘digital art is becoming a site of intense contestation as an embattled target of commodification and financialisation efforts. Simultaneously, digital art emerges as an important zone of resistance where artists and creative communities have an opportunity to help shape blockchain technologies in ways that challenge conventional perspectives on private property and the enclosure of cultural commons, rather than feeding into them’. M. Zeilinger: ‘Digital art as “monetised graphics”: enforcing intellectual property on the blockchain’, Philosophy & Technology 31 (2018), pp.15–41, at p.17, doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0243-1. footnote 1

- Ibid., p.37. footnote 2

- Sale, Sotheby’s, online, This Changed Everything: Source Code for WWW x Tim Berners-Lee, an NFT, 23rd–30th June, lot 1, available at www.sothebys.com/en/digital-catalogues/this-changed-everything, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 3

- Tim Berners-Lee quoted in A. Hern: ‘Tim Berners-Lee defends auction of NFT representing web’s source code’, The Guardian (23rd June 2021), available at www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jun/23/tim-berners-lee-defends-auction-nft-web-source-code, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 4

- The term was coined by Gavin Wood, who worked on Ethereum, in 2014. See G. Edelman: ‘The father of Web3 wants you to trust less’, Wired, (29th November 2021), available at www.wired.com/story/web3-gavin-wood-interview, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 5

- One telling example is Kayvon Tehranian’s TED talk at TEDMonterey in August 2021. Tehranian, the CEO and founder of the Foundation marketplace, started the talk with a reference to the early Web, John Perry Barlow and, of course, Stuart Brand. See K. Tehranian: ‘How NFTs are building the internet of the future’, TED (August 2021), available at www.ted.com/talks/kayvon_tehranian_how_nfts_are_building_the_internet_of_the_future, accessed 14th June 2022. Another popular reference in crypto discourse is Paul Baran’s illustration of centralised, decentralised and distributed networks (1964), an iconic trophy of the pioneering research of the 1960s that led to Arpanet, the first seed of the upcoming internet infrastructure. See ‘Paul Baran and the origins of the internet’, Rand Corporation, available at www.rand.org/about/history/baran.html, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 6

- M. Marlinspike: ‘My first impressions of web3’, moxie.org (7th January 2022), available at moxie.org/2022/01/07/web3-first-impressions.html, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 7

- V. Buterin: Response to ‘My first impressions of web3’, Reddit (8th January 2022), available at www.reddit.com/r/ethereum/comments/ryk3it/my_first_impressions_of_web3/hrrz15r, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 8

- See Chromie Squiggle, by Snowfro. 2021, Art Blocks, available at www.artblocks.io/project/0, accessed 14th June 2022. On Calderon, see R. Monroe: ‘When N.F.T.s invade an art town’, The New Yorker, (18th January 2022), available at www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-the-southwest/when-nfts-invade-an-art-town, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 9

- See ‘Learn about art blocks’, Art Blocks, available at www.artblocks.io/learn, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 10

- Endless Nameless, by Rafaël Rozendaal. 2021, Art Blocks, available at www.artblocks.io/project/120, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 11

- Z. Kaplan: ‘Announcing the “Endless Nameless” gift from Rafaël Rozendaal’, Rhizome (5th August 2021), available at rhizome.org/editorial/2021/aug/05/announcing-a-major-benefit-gift-from-rafael-rozendaal, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 12

- Sale, Christie’s, online, PROOF OF SOVEREIGNTY: A Curated NFT Sale by Lady PheOnix, 25th May–3rd June 2021, available at onlineonly.christies.com/s/proof-sovereignty-curated-nft-sale-lady-pheonix/overview/2058, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 13

- Sale, Sotheby’s, online, Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale, 3rd–10th June 2021, available at www.sothebys.com/en/digital-catalogues/natively-digital-a-curated-nft-sale, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 14

- E. Morozov: ‘About us’, The Crypto Syllabus (16th December 2021), available at the-crypto-syllabus.com/about-us, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 15

- D. Pinchbeck: ‘What revolution will be tokenized? Why the Left hates crypto, part one’, Daniel Pinchbeck newsletter (29th December 2021), available at danielpinchbeck.substack.com/p/what-revolution-will-be-tokenized, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 16

- S. Zizek: ‘It’s naive to think bitcoin & NFT give us freedom’, RT (8th January 2022), available at www.rt.com/op-ed/545405-bitcoin-nft-digital-control, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 17

- M. Gržinić: ‘Necropolitical screens: digital image, propriety, racialization’, The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 30, no.61–62, pp.98–106. footnote 18

- See G. Juárez: ‘The ghostchain. (or taking things for what they are)’, Paletten 325 (2021), available at paletten.net/artiklar/the-ghostchain, accessed 14th June 2022; and E. Morozov: ‘Geraldine Juárez on NFTs & ghosts’, The Crypto Syllabus (19th December 2021), available at the-crypto-syllabus.com/geraldine-juarez-on-nfts-ghosts, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 19

- A. Bartholl: ‘I don’t need to own art’, arambartholl.com (16th February 2022), available at arambartholl.com/blog/i-dont-need-to-own-art, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 20

- M. OLeary: ‘The case against crypto’, Watershed (3rd December 2021), available at www.watershed.co.uk/studio/news/2021/12/03/case-against-crypto, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 21

- Tante: ‘The third web’, tante.cc (29th December 2021), available at tante.cc/2021/12/17/the-third-web, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 22

- F. Stalder: ‘From commons to NFTs: digital objects and radical imagination’, Makery, (31st January 2022), available at www.makery.info/en/2022/01/31/english-from-commons-to-nfts-digital-objects-and-radical-imagination, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 23

- I. Bogost: ‘The internet is just investment banking now’, The Atlantic (4th February 2022), available at www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/02/future-internet-blockchain-investment-banking/621480, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 24

- T.C. May: ‘THE CYPHERNOMICON: Cypherpunks FAQ and more’ (1994), Satoshi Nakamoto Institute, available at nakamotoinstitute.org/static/docs/cyphernomicon.txt, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 25

- P. Zimmermann: ‘Why I wrote PGP’ [1991] (rev. 1999), philzimmermann.com, available at www.philzimmermann.com/EN/essays/WhyIWrotePGP.html, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 26

- D.J. Roio: ‘The Bitcoin Manifesto’, Bitcoin Talk (10th April 2011), available at bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=5671.0, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 27

- D.J. Roio: ‘Bitcoin, the end of the taboo on money’, Dyne digital press (6th April 2013), pp.8–9, available at files.dyne.org/books/Bitcoin_end_of_taboo_on_money.pdf, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 28

- See ‘The Left can't meme’, Know Your Meme (2016), available at knowyourmeme.com/memes/the-left-cant-meme, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 29

- Pinchbeck, op. cit. (note 16). footnote 30

- Yanis Varoufakis quoted in E. Morozov: ‘Yanis Varoufakis on crypto & the Left, and techno-feudalism’, The Crypto Syllabus (26th January 2022), available at the-crypto-syllabus.com/yanis-varoufakis-on-techno-feudalism, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 31

- See ‘What is the Byzantine Generals Problem?’, River Financial, available at river.com/learn/what-is-the-byzantine-generals-problem, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 32

- T. Rivers Ryan: ‘Will the artworld’s NFT Wars end in utopia or dystopia?’, Art Review (2nd December 2021), available at artreview.com/will-the-artworld-nft-wars-end-in-utopia-or-dystopia, accessed 14th June 2022. footnote 33

- Zeilinger, op. cit. (note 1), p.17. footnote 34