The films of Rory Pilgrim (b.1988) FIG.1 have a hallucinatory, utopic quality. This atmosphere is, perhaps, a by-product of the artist’s creation of diverse communities, wherein people discover kinship through tolerance, listening and compassion. One such example is the film RAFTS FIG.2, which explores the symbolism of the raft as a life-saving vessel. The project, which earned him a nomination for the 2023 Turner Prize, was undertaken in collaboration with volunteers from Green Shoes Arts, a mental health charity in Barking and Dagenham, who share their stories, poems and reflections on suffering and survival during the pandemic. ‘An oar of courage is what you must have to overcome the stormy waters of despair. The rolling waves will sink your raft without it’, says one participant, for whom animation offered a lifeline in their darkest moments. One found sanctuary in her garden, while another wrote a poem about an ancient tree that stands strong despite having its ‘innards ripped out’ FIG.3. These intensely personal contributions are interwoven with song and dance to produce a powerful polyphonic tapestry.

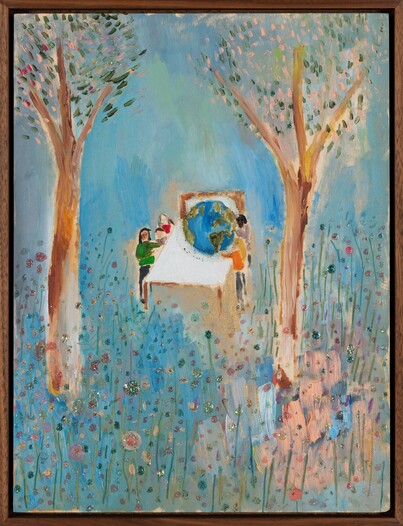

RAFTS was originally commissioned by the Serpentine Galleries, London, as part of Radio Ballads, a three-year social research project that examined the civic roles that art can play in transforming lives. As part of the Turner Prize exhibition at Towner Gallery, Eastbourne (28th September 2023–14th April 2024) FIG.4, the film is being shown alongside Pilgrim’s ethereal oil, pencil and nail varnish drawings FIG.5 FIG.6. Drawing and songwriting form the twin pillars of the artist’s socially engaged practice, which encompasses video, collage, storytelling and performance. His surname is an apt moniker for an endeavour that is profoundly spiritual.

Although the Turner Prize nomination has brought Pilgrim to mainstream attention in the United Kingdom, he was already well known in the Netherlands, where he has spent most of his time since completing a post-academic residency at De Ateliers, Amsterdam, in 2010. In particular, Pilgrim has garnered recognition for his collaborative works, which incorporate multiple voices and perspectives across generations. Two of his important mentors are the Dutch Fluxus artist Louwrien Wijers (b.1941) and the Sheffield-based poet and disability advocate Carol R. Kallend (b.1959). Pilgrim employs this dialogic approach to reflect on urgent issues, such as the climate emergency and the poor state of mental health services in the United Kingdom.

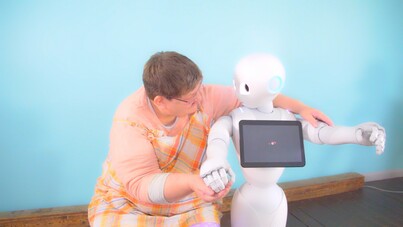

For example, his 2018 work Software Garden FIG.7 FIG.8, an eleven-track music video album underpinned by Kallend’s poetry, posits the ways that technology might be used to nurture human connections amid declining state social care. In the videos, participants of varying ages – including the singer Robyn Haddon (b.1992), another of Pilgrim’s regular collaborators, and the choreographer Cassie Augusta Jørgensen (b.1991) – touch tenderly, while others dance and take selfies, proffering kindness as protection against erasure in a post-digital capitalist world. Presented as a spatial installation, the work intersperses scenes of the natural landscape and diverse interiors, such as a flower shop and an nondenominational church, with edited footage of live concerts, performances and workshops orchestrated by the artist.

In 2019 Pilgrim was awarded the Prix de Rome Visual Arts award for his film The Undercurrent FIG.9 FIG.10, which brought together young eco-activists and members of a homeless shelter in Boise, Idaho. Again rooted in song – notably the magnificent, crystalline voice of Declan Rowe John – the film features discussions about homophobia and climate catastrophe. At the end of the film the activists march to a hilltop and shout into the rising sun FIG.11: ‘We need our earth. We need compassion. We need our lawmakers. We need our government to fucking listen’. Yet Pilgrim refuses to let pessimism prevail. Characterised by a spirit of non-judgment and inclusivity, his works embody hopefulness, offering – in both form and content – a model for harmonious coexistence. Elizabeth Fullerton interviewed the artist about RAFTS, the Turner Prize, spiritual communities and polyphony.

Elizabeth Fullerton (EF): How was the experience of participating in the Turner Prize?

Rory Pilgrim (RP): I have mixed emotions. It’s been very meaningful to be put forward and be able to show my work to a wider audience, but dealing with the media response has been difficult. What has upset me most is the way critics have talked about those I’ve worked with – one called their poetry awful.1 Another said that the film wasn’t compelling enough to be nominated.2 And I just thought: can’t they read the room? Can’t they just listen to what those in the work are actually saying and expressing? It’s a film made within a certain context, born of a certain intimacy. It’s a mental health group. It’s been eye-opening in terms of the gulf between the response of critics and audience – based on the direct messages I receive from people. But in the end, it’s the voices of the critics, who write for national newspapers, which are platformed.3

EF: It doesn’t seem relevant to apply the criteria of conventional art criticism to creative work made by people who haven’t been to art school, whose art comes from a different place and doesn’t speak to the language of different ‘isms’.

RP: It also feels like a very British response. I don’t have to deal with this in the same way when I work abroad, but in the United Kingdom art is categorised into a binary system of what is considered ‘community arts’ and what is allowed in the gallery space. I see a level of hypocrisy when articles will in the same breath speak about exclusion and inclusivity, and then call those I’ve worked with names, essentially to delegitimise their voices because they’re not coming, as you say, from art school training. Art in this country is expected to be funny, satirical, shocking or clever. But if it gets too personal or doesn’t fall under ‘kitchen sink realism’, then it becomes ‘too close’ for some people. I think that critics can act as gatekeepers to existing models of power, and often don’t want to listen or take seriously what a person has to say or how they express themselves, or even speak of hope. In the end, RAFTS is a film about art. It engages with a charity that provides creative resources for people as a coping mechanism.

EF: Sincerity has had a problematic place in recent British art.

RP: I’ve lost count of the times that I’ve been called sentimental, wishy-washy or gentle. Sentimental is often used as a pejorative term, especially in the United Kingdom, but its original meaning didn’t carry those connotations, it simply meant ‘to feel’. It seems that people, especially those in power, can’t cope with someone expressing genuine emotion about how they feel. Instead, we prefer to deal with things by being satirical, ironic or by academicising the subject; we’re more comfortable with something remaining desolate than actually improving it.

It’s complex, but sometimes I also think that the words used to describe my work relate to experiences of gender. Although I’m in a male body, my nature is much more on the ‘feminine’ scale and I can’t help but feel that words like ‘gentle’ and ‘wishy-washy’ are some ridiculous extension of classroom homophobia or queerphobia. I would say that my work exists very much on a queer spectrum, with many things merging together, but it also doesn’t have an outwardly queer aesthetic nor is it defined by sexuality. I think that people are confused or even intimidated by that. It seems that in contemporary art we can only ‘feel’ in a certain kind of way and must deplore something that is ‘gentle’.

If the work was just about me, I might have not looked at the media responses. But when you’re working with sixty to seventy people, as I did for RAFTS, there’s a responsibility of care: you don’t want others that you’ve built up trust with to be hurt. The most meaningful thing for me is when I’m contacted by audience members personally. That’s all I can ask for. We create this work to make sure people feel connected, that they’re not alone and that there are structures out there, that it’s not all just hopeless.

EF: Your presentation in the Turner Prize exhibition also includes intricate drawings of rafts and flower-filled idylls FIG.12. What is the role of drawing in your practice?

RP: There are two main threads to my work: I’m always writing songs and I’m always painting. It’s a bit like a garden; there’s a symbiosis, one generates the other or they move in parallel. I have hundreds of sketchbooks FIG.13 FIG.14, which I use for drawing and figuring things out as I’m making, and it’s a very personal practice. The drawings also provide a basis for me to work with other people. I started RAFTS because I drew a raft FIG.15: it’s very literal and unmediated. A lot of it is finding visual anchors. I try not to think too much about the connection with poetry or a more illustrative way of working, I just draw. But I’m essentially lyric-writing. In RAFTS all of the drawings feature rain in some measure and that fed into the songs. For example, the first song is called ‘Tomorrow’s gentle rain’, so it’s all very interconnected.

EF: In a sense, can your drawings be understood as a raft?

RP: The drawings are maybe a reflection of my own inner world, but it’s from there that I can do this kind of work and connect with others. And they also provide me with a form of escapism or solace when things feel difficult. I can get lost in making a drawing. I’m increasingly interested in the imaginary and that’s why my work isn’t just this kitchen sink realism. I’m much more tapped into a spiritual side of things. Many of the people that I’ve worked with have religious faith, which for them is an important source of strength. Sometimes in contemporary art there’s an assumption that we live in a post-secular time and that’s ludicrous to me.

EF: Your father is an Anglican vicar so your childhood home was halfway between a public and private space. How has that informed your practice?

RP: For a church family, the home often is an extension of the church. It’s usually in the same grounds, and we had no separate phone line. People from the parish frequently came to the house, and events and meetings were often held there, meaning it became a de facto community space. Much of my work is trying to understand that experience and the complexities of community. Dealing with these subjects, and how they are felt, is inherent to who I am. I spent four years singing in a cathedral choir and grew up with the mundane yet important intricacies and politics of organising church coffee mornings, as well as situations in which people who were homeless or in very difficult circumstances would come to our house. Then when I was a teenager and could make decisions for myself, I defected to the Quakers, which has really informed the way I work. There’s not that much difference between how my work looks and how a Quaker meeting can look or feel.

EF: In what way?

RP: Quaker worship is a rhythm between speaking and listening. Anyone can speak within the silence, but you don’t speak immediately after another person, instead you give it three to five minutes. In my films I don’t necessarily have silence, but the songs create this rhythm between speaking and listening. A lot of my early mentors were people who worked in social peace and justice. An important woman from the Quaker community called Helen gave me Suzi Gablik’s The Reenchantment of Art (1991) and Mapping The Terrain: New Genre Public Art (1995), which is edited by Suzanne Lacy, and this first introduced me to socially engaged art.

EF: Your work seems rooted in notions of care and compassion.

RP: When I was studying I worked as a part-time carer for an individual. I thought that after I left art school I’d go into the care sector, so this is obviously very much an intuitive discipline for me. I’ve been close to people with terminal illnesses, so it’s always been a part of my life. But what I feel strongly about, in terms of the work I make, is that it should collapse the binary between caregiver and carer. In the end we all are receivers and givers of some form of care.

EF: In your practice, you often platform multiple voices and perspectives. Do you think that this approach relates directly to the fractured state of our present day?

RP: It’s hard to think of a time when care and compassion weren’t needed. I can also trace the difference from 2005, when I was studying at art college, to now, when we seem to be constantly at a crisis point. The hardest task is how to simply be in this time and to not feel nihilistic or surrender hope.

EF: You’ve spoken of your process as ‘activism through the lens of beauty and joy’.4 Do you find that often there’s an expectation for hardship to be depicted through abjection?

RP: Very much so. Certain power structures expose that typically people don’t want to see people who’ve experienced pain – whether on account of class, race or sexuality – be happy or joyful. We’re all capable of experiencing harm and doing harm, and experiencing pain and causing pain. But if you deny people their ability to also show beauty, joy and humour, it removes their agency. In the most painful of situations, people use glimmers of joy or beauty as a survival mechanism and it’s a reality.

EF: That seems to be ultimately what your work is about.

RP: I hope so. Of course it’s not that the work is devoid of anger or pain. The Undercurrent ends with a group of young people running up a hill and voicing all of their frustrations. But I’ll always look for moments that try and get us out of it, or provide us some space in which to comprehend it. That’s what art has the great capacity to do. Not all art needs to be like that, but it’s how I operate.

EF: I’m reminded of the concept of ‘pocket utopias’ coined by Hammad Nasar, the lead curator of the 2021 Turner Prize show, which featured five collectives.

RP: It’s like Ursula K. Le Guin’s description of the story as a ‘medicine bundle’ in ‘The carrier bag of fiction’.5 I was drawing bags long before I read Le Guin, but that text made me understand that I was thinking of the world as one gigantic bag. The RAFTS paintings have a lot of purses FIG.16, and there’s even a song called ‘An amazing purse’. Le Guin beautifully puts into words the potential of the story or the work of art, and then we arrive at a set of tricky questions: who’s telling the story? Who’s in ownership of the bag? What legitimises the telling of that story?

EF: What particularly draws me to your work is that so many stories are told at once. Does the term ‘polyphonic’ feel an apt metaphor, going beyond its musical connotation?

RP: Definitely. The beauty of polyphony is that it’s made up of many voices but what’s important is how those voices interact. Sometimes it can create the most evocative harmonies or textures or layers, but you can also have incredibly chaotic polyphony. This can be an amazing thing, but it can also make listening quite difficult – the more complex the polyphony, then the more complex the listening required. It’s not just this regimented homogeneity. I do intuitively relate to a polyphonic form of collaboration or community compared to a homophonic one, in which we all have the same voice.

EF: How do you preserve individual autonomy within the collective?

RP: For me the ideal is to work with a group of between six and eight people, so that I’m able to build up a meaningful relationship that can be nurtured, and I can respond to the needs of each person. With RAFTS I couldn’t have done that work if members of the group weren’t so caring towards one another. They created an atmosphere of trust; the strength that happens when you feel held by that amount of people becomes really powerful. As a facilitator I find it hard to hold bigger groups because that level of intimacy or care starts to crack.

EF: How do you generate your communities?

RP: There was a moment around 2015, before Brexit, when I felt like words didn’t mean anything – we just didn’t trust them or have the right ones to speak about what we were experiencing. So I put out open calls and I looked for people who had been part of cultural and political movements in the 1960s and 1970s. I wanted to create a dialogue about what words mean to them and how their connection with them has changed over their lifetimes. I reached out to poetry groups, political groups, spiritual groups, and met with each person who responded. From these meetings, a group was formed, which resulted in a performance called Words are not signs, they are years FIG.17 and then the film Sacred Repository #3: THE OPEN SKY FIG.18.

EF: There seemed to be great generosity from your participants to share with you and the public. Is it common to encounter such openness in these groups?

RP: As a facilitator, I have to be the barometer of what feels right. For example, you might be in a group where someone overshares and as a result you sense that someone else is having a physical response, so you go into overdrive to navigate the situation. A level of flexibility or malleability is important. It’s about being responsive and nuanced with each group, and creating an infrastructure in which people feel held. This can be on the most basic level: offering a place that is warm and welcoming, with tea, coffee and good snacks.

EF: Your films involve performance and therefore a level of self-awareness. How do you get past the mediation that comes from filming to arrive at the authenticity that defines your works?

RP: I’ve learnt that I have to go with what’s right for each person, which is quite a long process. Often, before filming anything, I’ll organise a workshop with them about the role of the camera: why we record, which recordings have been an important part of peoples’ lives, how they feel about the camera and about filming one another. It’s about building trust, but also I think that a person will quite naturally engage with the camera in a way that feels authentic to them. With RAFTS, some people wanted to do that – not necessarily in a theatrical way, but in order to feel strong and in command of themselves. It’s truthful to them, whereas other people ignored the camera completely. I’m often the one filming, so they’ve built a trust with me to do that and it shows in how I frame things.

EF: You’ll have a solo exhibition this spring at Chisenhale Gallery, London. What are your plans?

RP: I’m planning to start workshops with those incarcerated in HMP Portland, thinking about what it means for laws to be inscribed, through the ways we write, speak and listen. From my previous experiences working with homelessness services and those who have experienced incarceration, I’m aware of the different experiences of literacy and also the effect that a criminal record can have on a person for the rest of their life. The Prisons Strategy White Paper, a report published by the Ministry of Justice in 2021, inhumanely infers that incarcerated people are beyond repair, that they have been written off by society. I’m interested in how we rethink or reimagine law – both when it fails us and when it protects us – and what processes are needed to rewrite it. I’m essentially developing a screenplay through dialogue and looking at different experiences of the criminal justice system, mainly focused through working with people in Portland.

EF: Will song and drawing feature?

RP: Yes, but it’s also about examining the tensions between what’s said and unsaid, what’s seen but not heard, and what’s seen but not believed. A bit like RAFTS, a starting point has been thinking about the metaphor of kicking things into long grass, like a problem you don’t deal with. That’s been an important starting image. There’s a series of fresco panels by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in Siena called The Allegory of Good and Bad Government (1338–39). I’m thinking of creating a frieze on the external walls of the gallery inspired by that, but it’s still in the early planning stages and will naturally grow from working with others. This work in many ways is a culmination of The Undercurrent and RAFTS – I’ve arrived at a place where the question of ‘law’ and experiences of the criminal justice system feel paramount. In the end, we can’t protect each other and our precious world in a system that refuses to truly listen to those whom it denies a voice.

Footnotes

- See S. Hubbard: ‘Turner Prize 2023: a regional awakening – Towner Eastbourne’, Artlyst (2nd October), available at artlyst.com/reviews/turner-prize-2023-regional-awakening-towner-eastbourne-sue-hubbard, accessed 21st December 2023. footnote 1

- See H. Judah: ‘Turner Prize 2023: Jesse Darling is my pick to win – but we need to rethink this award altogether’, The i (27th September 2023), available at inews.co.uk/culture/arts/turner-prize-2023-jesse-darling-pick-win-rethink-award-2645872, accessed 21st December 2023. footnote 2

- See R. Barry: ‘This year’s Turner Prize nominees display a weariness with institutions’ Apollo (3rd October 2023), available at www.apollo-magazine.com/turner-prize-2023-darling-walker-leung-pilgrim-review/, accessed 21st December 2023; and J. Lawson-Tancred: ‘The Turner Prize exhibition promises to tell us something about the art of our time. in 2023, it’s complicated’ Artnet (28th September 2023), available at news.artnet.com/art-world/turner-prize-2023-2368770, accessed 21st December 2023. footnote 3

- Rory Pilgrim, quoted from ‘Activism can come from a space of joy’ Tate (27th September 2023), available at www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/rory-pilgrim-30536/rory-pilgrim-activism-can-come-from-a-space-of-joy, accessed 21st December 2023. footnote 4

- U.K. Le Guin: ‘The carrier bag theory of fiction’ (1986), available at otherfutures.nl/uploads/documents/le-guin-the-carrier-bag-theory-of-fiction.pdf, accessed 21st December 2023. footnote 5

.jpg)

.jpg)