Phoebe Collings-James (b.1987) is a multi-disciplinary artist who works with painting, sculpture broadly defined, sound and clay. Her recent solo shows include A Scratch! A Scratch! at Camden Arts Centre, London, 2021, and Relative Strength at Arcadia Missa, London, 2018. She is also a member of Black Obsidian Sound System (BOSS) – a collective established in 2018 for queer, trans and non-binary Black people and people of colour in the arts – who were nominated for the Turner Prize in 2021. Here she is interviewed by the art, craft and design historian Tanya Harrod.

Tanya Harrod (TH): You have a genius for mixing ecstatic sound with research. How important is it for you to integrate the aural with the visual?

Phoebe Collings-James (PC-J): Sound pops up a lot, as part of my work with BOSS and sometimes through DJing. These things are fun and communal, although I wouldn’t say ‘not so serious’. Rather, they’re a different kind of expression. It’s serious. I’m always serious about everything, even if it’s enjoyment, but I think that those things are ways for me to listen to, feel and just be in community with music. When it comes into my art practice, that’s much more about sculpture, drawing and speaking as a way of articulating myself. Speaking isn’t my preferred mode of communication. Part of that is because I end up talking too slowly or too quickly. Often, especially if I’m responding to a question, there will be five, then twenty, thoughts and directions going on in my head at once. This is something I’ve noticed in my own work – across sculpture, sound, film and drawing – where there are possibilities for layering, sampling, cutting and pasting. It’s also something that I find is true of most answers, in that they are often layered and there are different, multiple truths at once. Sound enables that kind of articulation.

TH: For your exhibition Expensive Shit at 315 Gallery (now Jack Barrett Gallery), New York, in 2017 FIG.1, you integrated oral history research into your family and Jamaican culture – particularly for the installation Primordial Soup (2017).

PC-J: Recording those voices felt important. On the one hand, they are my family members and I want to remember their voices and the things they’ve shared. Recorded in sound, they can have echoes and they can also be portals or connections to a whole host of memories and feelings. On the other hand, the linguistics and accents catch moments in time. My grandparents on both sides lived in the East End of London – their Jamaican and cockney accents don’t exist anymore. Only versions. It will be the same for generations in eighty years’ time. Likewise, my aunts who lived in Jamaica had accents from a very specific time – pre-independent Jamaica – and you can really hear the mixture of a deep Jamaican patois with this colonial formal English, which will never be heard again. So, those things are another dimension that interest me in terms of including voices: the tones and song of voices and their political and cultural references.

In that show, one of the things I thought was most successful was the loud speaker held in a net FIG.2. The sound system is linked so directly to Jamaica and the Caribbean culture there. But here it was suspended in a black safari net and I was hoping to create the effect of simultaneous tension and relief. Viewers to the exhibition would most often sit down between the two speakers, between the panning sound. There were two silver pieces of Mylar taped to the wall like curtains; they had been folded up so still had a square pattern imprinted on them FIG.3. They were blowing slightly, lifted by a fan placed out of sight, which was a gesture towards the wind and light moving across tin roofs in Jamaica. The idea was to conjure up something that was a mixture of things and sounds, such as being on the bus in Jamaica and hearing Adele playing. It’s common to hear white British pop singers mashed in with Jamaican songs on the bus on a Sunday morning. I guess the sound work was a way to articulate this primordial soup without being overly didactic, but instead immersive and tactile.

TH: The music that plays a significant part in your work is often arrived at through collaborations. Could you talk about that – for example, your work with SERAFINE1369?

PC-J: SERAFINE1369 is the artist name of Jamila Johnson-Small. We met at school when we were sixteen and have been collaborators ever since. They trained at dance school and so most of their work incorporates some form of dance or live performance, and now a lot more exhibition and space-making and facilitation. Jamila works with darkness so there would often be low light punctuated by strobes or a fluorescent bulb. The first couple of times I made these works, I thought about layering sound and articulating the prompts that Jamila had given me, which might be a poem or a certain reference. From then on, I started to incorporate some of that sound work in my own shows.

TH: Jamila went to dance school and you went to Goldsmiths, University of London. How much do you think you owe to your time there? Did it feel like a radical place to you?

PC-J: Critically, when I look back on it now, no. In many ways it wasn’t a good experience for me, for all the reasons that other people have cited issues with it: structural and systemic racism, the conservative nature of the university as a business and capitalist pressures crushing artistic joy and potential. On the other hand, I was nineteen and it was an absolute playground and joy. I experimented in the different studios, especially photography, and I had some wonderful technicians and teachers. Some of that was overshadowed by a number of pretty awful experiences with academics who were classist and racist. No institute is wholly immune from that and it comes down to how you deal with it. No one can control every action of a person or a group of people; there will always be conflict and problems, but it’s about the processes in place to listen to people and address those issues.

TH: So, was the best about thing about Goldsmiths the access to ways of working and making?

PC-J: Yes, I think one thing about Goldsmiths that was unique at the time – which is now prevalent across most art schools – is that you didn’t have to commit to a single pathway. This likely set the tone for the way that I work now, across mediums. I do think of myself as a sculptor, even when I’m making sound work, and Goldsmiths introduced me to the expansiveness of what this approach could mean. Being given a studio from the outset and the opportunity to just make work gave me discipline in terms of having an enduring studio practice. So there were definitely good things, but overall there was a lot of unlearning that had to be done.

TH: The college offered a narrow definition of radicalism perhaps?

PC-J: Definitely.

TH: Do you think that things have expanded in the last few years, in terms of the artists that are being looked at and thought about? Has there been a minor revolution that might feed back into art schools? I’m thinking of the impact of Black Lives Matter (BLM), for example.

PC-J: I think so – certain things have changed for the better even as other things are getting worse. In terms of BLM, I hope that it’s changed and galvanised individuals and communities, although I don’t think that institutions and their structures have permanently changed. There’s been a lot of temporary changes and it will take a lot of fighting to hold them to their promises, which already are seemingly being forgotten. Their next agenda is an ecological one, which is often seen as distinct from issues of racial justice, although they are clearly intrinsically linked. Chattel slavery and the practice of treating people as commodities are completely in line with the industrial exploitation of land, people and materials. I don’t think that the connection is made enough between white supremacy and discourses around the climate crisis, and for some people BLM is just this slightly annoying thing that we’re going to have to deal with because it’s simply too loud not to now. I’m thinking about the overarching structures of society in the United Kingdom. I’m sure individuals care but this needs to be accompanied by action; empathy is not enough.

TH: Could you say a little about your first encounters with clay, was it during your residency in Nove in 2014?

PC-J: Nove is an old ceramics town in Italy. At that point, local artisans were mainly making souvenirs. In some places they were also producing larger pots and plumbing ware and things like that, but a lot of the studios were running on half capacity. In most of them, the age range of workers was fifty to ninety, so the industry was obviously slowing down. I was in a studio with an amazing group of ceramicists and potters, each with different intentions and approaches to clay. I don’t speak Italian and most of them didn’t speak English so it was mostly a process of watching and listening, then me making something, my mentors laughing, then showing me a better way and again me watching and trying again. It was a beautiful way to understand the material of clay. I applied this learning to making guttural tongue forms FIG.4 FIG.5, which I showed in Choke on Your Tongue at the Italian Cultural Institute, London FIG.6 FIG.7.

This was the seed that I tried to find my way back to, but I suppose it took four years. I returned to Italy briefly in 2015, and then the next time I touched clay again was in Brooklyn in 2018. I signed up for a day course in throwing and immediately realised that I wasn’t great at it. This was anathema to me because I’d assumed I’d be wonderful because I had such a deep connection to clay, and I was a sculptor and an artist. But I was just ordinary, like everyone else in the class. However, the beautiful thing about this course – which I now realise is unusual – is that you were allowed unlimited access to the studios. It was January, in a bleak winter, and I spent all of my time there for the next six months, adamant that I was going to learn how to throw. A couple of years later my Camden Art Centre Freelands Lomax Ceramics Fellowship started, in October 2020. But in the intervening period, I didn’t have any solo exhibitions to work on.

TH: What were you doing?

PC-J: Mainly, I was working with Jamila on a live work, Sound as Weapon, Sounds 4 Survival FIG.8 FIG.9. We did a residency at Wysing Arts Centre, Cambridge, in early 2018, while I was still living in New York, but I came back for the residency. The piece included movement, sound and the participation of other artists, and ended up being a touring performance for the next year and a half FIG.10. A lot of the process of forming and scoring the work came through the dialogues that were happening with the other residency participants, who were all Black women, or non-binary people who felt a relationship with womanhood in some way, whatever that term might mean for them. That was the invitation: to think about Black women, Black woman-ness, what it meant, what it could hold and what could be opened up or known through us creating an intentional space together to make work. At the same time, we were exploring questions of what an anti-assimilationist practice might sound like and thinking through our bodies about the resonance of percussion.

TH: Can you tell us about the exhibition that came after this period, from your residency at Camden Arts Centre, which was called A Scratch! A Scratch! FIG.11?

PC-J: I had an overarching idea about Romeo and Juliet, specifically act 3, scene 1, in which Mercutio is killed by Tybalt. There were a number of intersecting reasons why it came into my consciousness: things that had happened in my family, ideas of love and loss, the homoeroticism of the scene and what it means to perform strength when you’re wounded and dying. There were so many different threads that I found vividly, crudely and humorously embodied in this scene. It felt like the perfect way to trickle down into these different realms, or layers of articulation.

TH: All of your titles – of shows and of individual works – seem full of meaning. Do you think of yourself as a literary artist?

PC-J: Yes, I think I am; more and more my own lyricism and poetry has found its way in, as well as references from other places, quite often music. The title for the clay torso armour shown in the Camden exhibition, The subtle rules the dense FIG.12 FIG.13, comes from an anonymous book titled Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism (1980). I find words and their arrangement a vital element that can also be playful. Even the title A Scratch! A Scratch! is simultaneously full of playfulness, doom and death.

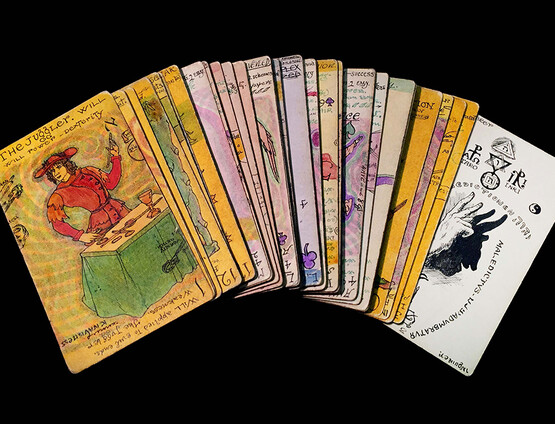

TH: Can we talk about your interest in tarot? Clay is a chancy material, not least when subjected to firing. Tarot confronts you through chance, is that why it interests you? As part of the Camden residency, you were in conversation with the tarot practitioner Daniella Valz Gen.

PC-J: Daniella had been an incredible guide in terms of tarot and the sound work at Camden was partially made up of poems that I had made at their tarot writing sessions. They set up a tarot circle in which participants would meet monthly and work through the Major Arcana. Daniella collated extracts from different books and references of people speaking about a specific card and we discussed its symbolism and layers. In relation to the clay, there is chanciness but also an element of divination. When ceramicists fire with soda, gas or wood, they often make a kiln god or a salt offering to the kiln – this is a wish but also a recognition of the magic that occurs in the alchemy. Finally, the way you observe the form, especially with pottery, is looking for that moment of magic. To an extent, tarot is about making connections through images, oracular play and a connection to magic and divination.

TH: You took part in the group exhibition Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics and Contemporary Art at Two Temple Place, London, in January 2022 FIG.14, which was curated by Jareh Das and subsequently travelled to York Art Gallery. It was an attempt to recuperate the achievements and identity of Ladi Kwali, a traditional northern Nigerian woman potter who was initially ‘discovered’ by the Muslim Emir of Abuja and subsequently by the studio potter Michael Cardew, who set up the Pottery Training Centre in Suleja (then Abuja) in 1952 under colonial rule. Cardew persuaded Kwali to translate her handbuilt, low-fired earthenware pots into glazed high-fired stoneware and to perform her skills before large audiences in the UK and North America. How did these events strike you: did you view Cardew’s bringing her work to a wider audience as an act of liberation or appropriation?

PC-J: I don’t think there is a choice: you’re a colonial subject and in navigating that, there is the potential for transcendence, but it’s a constant dance between compromise, resistance, taking what you need and figuring out what you can endure. When I think about Kwali and Cardew I have to remind myself of her agency – whatever that can mean within the context of colonialism. And because, apart from the few insights in your book The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew, Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture (2012), I still don’t know much of her voice. So everything is, to some degree, conjecture, and I don’t want to undermine her autonomy knowing that she clearly had a desire to work with the materials and processes Cardew was offering. Although I consider Cardew and the training centre, which was a result of his appointment by the Nigerian government to the post of Pottery Officer, as hugely problematic, I also try not to regard her as a subjugated person because that’s not the impression I get and it would be too reductive. Agency under racial capitalism most often looks like compromise.

TH: I agree that we don’t hear Kwali’s voice, except through her work.

PC-J: What really became apparent is that she was an artist. This is true also of Halima Audu, Ladi’s co-worker at Cardew’s Pottery Training Centre, which is demonstrated in something as simple and complex as her screw-top bottle. There would have been a lot of times when Kwali and Audu were working between themselves – they were moving the practical and artistic forms of their traditional functional water jars to this place at Abuja, where the main ambition was to make something new. Some of that energy was mirrored in the different contemporary artists that Jareh included in Body Vessel Clay. Even though we were not all directly in the same community as one another, something was happening there, a kind of communal magic similar to what had happened in Nigeria.

TH: I’d like to talk about your pedagogic Mudbelly projects that put me in mind of Theaster Gates’s projects in Chicago. I know that you were invited by him to work at the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts this summer. Do you feel a strong impulse to give back to the community?

PC-J: I started thinking about this in 2019 as a reaction to the studios where I was learning, in London and New York. Both took place in industrial spaces that would have previously been occupied by Caribbean or African American workers, but that was not reflected at all.

TH: Because learning to make ceramics is very much a white middle-class hobby?

PC-J: Yes. The cost of learning didn’t seem exploitative, but there are other access needs being ignored that aren’t to do with finance. People need to be aware that certain groups of people don’t have access in any way as a result of disability or, more culturally or socially, race or class. Mudbelly was in reaction to that. It’s a space that offers a range of free ceramics workshops to Black students, taught by Black artists and potters, which focus on intergenerational communities in London. I was also thinking about the singular pedagogy being taught in such places, which is perhaps a continuation of the early studio pottery movement’s interest in Japanese or Korean pottery. They actively didn’t look at someone like Kwali. The idea that I was taught to coil and didn’t know who she was until much later seems ridiculous to me. Who does coiling better? I’d been introduced to Magdalene Odundo and heard her speak on the radio about Kwali. There was the kernel of an idea and I started trying to put it into action and get funding, and then it was delayed in 2020 because of lockdown. The first class was in April 2021.

TH: How do you explain the move towards clay in the art world that we have seen in recent years?

PC-J: I see clay as an alternative to the hyper-acceleration of capitalism, far-right governments and technology. The kind of iPhone, iHand, iPalm reaction has stimulated artists to work with clay as an alternative. Even though it involves huge industrial processes that are complicit in rare earth mining, the unconscious feeling is one of being connected to soil. There is a publication from 1990 titled Passion: Blackwomen’s Creativity and the Arts, which is full of different things: poems, texts, images and interviews. One striking thing is that a lot of the work talks about craft and the ways in which processes are used in artistic practice and in resistance to the boom of capitalism that came in the 1980s, and also the aftershocks of austerity through the poll tax riots and Margaret Thatcher. I think we are living in a similar time – this thirty-forty-year cycle seems quite clear now.

TH: Back in the 1980s craft appeared to operate as an alternative to a highly capitalised art world. But now it seems that craft has been sucked in by the art world.

PC-J: I guess that’s one thing that wasn’t happening thirty or forty years ago. I went to Art Basel Miami in December 2021 and was struck by the prevalence of textile works and craft practices. I don’t know what significant this will have: will the breadth of craft experience finally be recognised? I think about someone like Doyle Lane (1925–2022), whose ceramic works were made at the same time as the Californian modernist movement. Obviously, for many reasons, he was relegated – also for being African American, but those craft and race narratives were not seen in connection. Now, for better or worse, they will be solidified in a mainstream canonical art narrative. Theaster Gates’s and Simone Leigh’s work both make a precedent for that.

TH: Arguably this is a wonderful moment when one thinks of a figure like Odundo who had, up until recently, been sequestered in a rather narrower ceramic world.

PC-J: I remember meeting a gallerist who put on a show that included some of Odundo’s work. I must have referred to them as pots and he said, ‘no they’re not pots, they’re sculpture’, and I just thought ‘oh, you’re missing it, because of the elevation that you have given to sculpture’. In my mind there is no distinction in terms of rank or reverence between sculpture and a pot. The word ‘pot’ acknowledges some very important threads of history and Odundo’s place in it. I see them as simultaneously sculpture and pot. Pots are always contemporary to their time and the needs, consciousness and art of that time.

TH: There have been limitations on our vocabulary until recently. Just to end, I’d like to talk about your large, spectacular 2021 piece acquired by York Art Gallery, titled How many times can I surrender to you? (your living has taught me how not to die) FIG.15. It brings to mind the expressive nature of slip as a painterly tool. Makers of vernacular slipware used liquid slip with swift and decisive movements. As a drawing tool, there seem to be linkages with slipware as folk art, and with Abstract Expressionism, and all kinds of automatic drawing processes.

PC-J: I’m interested in where those two potentially polar opposites collide. That they’re not really parallels but they are spirally, wiggly lines that interconnect. In terms of my own references, some of the pots I’ve been most struck by have been ones that contain slipware, whether on harvest jugs or using your fingers to make patterns. It feels very intuitive to me. Slip has its own form.

TH: How was How many times can I surrender to you? (your living has taught me how not to die) made?

PC-J: It’s mostly brushed, quite sloppily. An artist recently remarked that the smaller, similar piece Don’t despair (infinity loop) FIG.16 looked like a performance piece. In fact, the preparation was done quite carefully. I didn’t want the clay slabs to shatter; the process of making the slab with integrity is a careful one. And then often I have to wait for a certain, more performative moment when I have a connection, keeping the slabs wet under plastic until I’m ready for them. It links back to these moments of divination and connection – when I’m able to articulate what has been on my mind or the locus of my research. When I make the final work, I sometimes work from drawings, but more often I refer to an ongoing library of symbols, signs and gestures from memory. Those moments when I finally do work on the clay are usually a single sustained length of time that becomes almost automatic.