Hanna Tuulikki

by Greg Thomas

Articles /

Artist profile

• 10.05.2024

Over the last few years, the British–Finnish artist Hanna Tuulikki (b.1982) has gained recognition for her immersive, performance-based works, evoking our relationship with the more-than-human world at a time of unprecedented ecological crises. As she puts it, ‘I'm interested in world-building’ – a tenet that is reflected in her working methodology, which moves freely between music, dance, performance and conceptual art.1 Her most recent large-scale performance, the bird that never flew FIG.1, is a case in point. A fifty-minute song-cycle for three voices, accompanied by bowed psaltery, electronics and field recordings, it is influenced by religious plainsong, especially by the monophonic compositions of Hildegard of Bingen. The lyrics evoke the climate emergency while also serving as phonetic transpositions of the alarm calls of endangered birds – the signals that birds use to warn others in an area, including members of other species, that a predator is nearby. Tuulikki and her co-performers, Mischa Macpherson and Lucy Duncombe, wore black robes with protruding pleats at the back; tall cylindrical hats, which recall the headdresses worn by Orthodox Christian clergy; and large red feathered eyelashes. A triangle of red translucent fabric hung over their mouths FIG.2, a semi-disguise that alludes to the face coverings often worn by protesters.

As is always the case with Tuulikki’s work, there is an intricate conceptual architecture at play here, emphasising, in particular, how animal behaviour can teach us mutual care and interspecies empathy. But first and foremost, the bird that never flew appeals to the heart and gut, as Tuulikki notes: ‘That feeling of being moved on a body level is so transformative. It can create change, even in little ripples, in a way that conveying things rationally and analytically just can’t’. Indeed, this notion of being ‘moved on a body level’ might be the most significant underlying element of the artist’s practice, even while considering its connections to experimental music, contemporary dance, aleatoric scores, concrete and sound poetries and global folk cultures.

‘I wanted to be a dancer when I was a kid’, Tuulikki recalls, ‘then I started working with movement again in my thirties’. As a child she spent holidays in northern Finland, where her mother’s family are from, in forests and by lakes: ‘I remember my mum telling me stories about my aunt singing cow-calling songs […] Of course, as an adult coming back to that heritage, I’ve discovered more complex perspectives, and I’m wary of having an overly romantic view of it’. Her strong connection to flora and fauna was also informed by a period living in a mobile home – ‘it’s like existing outside. You can hear everything all the time. I was so aware of the dawn chorus, the weather, the critters in the night’ – as well as her childhood in Brighton, where her family lived on a crescent next to a park. ‘Because I made friends with a lot of old people who kept on dying’, she says laughingly, ‘I went to many funerals, so I started making bird funerals for the birds that died in the park’. ‘I’ve always been extremely earnest’, she adds, ‘My drag king name is Ernest McEarnest’.

Although it is a term that has a somewhat problematic place in contemporary art, it is partly this earnestness that secures the value of Tuulikki’s work: its openness to big, (seemingly) simple emotions, such as love, fear and sadness, which are often defined in connection to human–animal relations and environmental catastrophe. However, her studies at Glasgow School of Art initially appeared to invalidate such creative approaches. ‘I started making this really dry work, thinking about the artist as a pragmatic problem-solver, and it just wasn’t making me happy […] I was always thinking about the ecological crisis, but I remember just before my last year of my undergraduate degree having this breakthrough where I gave myself permission to use music and the voice to explore those things’. It was also during this time that Tuulikki first used birdsong as source material, slowing it down and manipulating it in different ways.

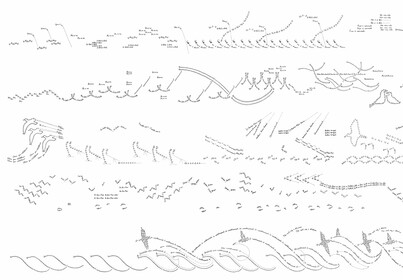

An early result of this new direction was Air falbh leis na h-eòin – Away with the birds (2010–15). The crux of this long-running project, which also explored Gaelic folk song, was Tuulikki’s musical composition Guth an Eòin | Voice of the Bird (2013), a piece for a female vocal ensemble combining fragments of songs and poems from Hebridean culture that imitate bird song. Iterations of the piece were performed at Tectonics Festival, Glasgow; at Tramway, Glasgow; and on the Isle of Canna in 2014 FIG.3 FIG.4. The artist also produced a visual score FIG.5, recalling 1950s and 1960s aleatory compositions, with fluid, rhythmic mark making and pictorial, ornithological flourishes.

Since this project, Tuulikki has been exploring what she calls ‘mimesis as a practice of becoming-with’. She describes mimesis as ‘a process of attunement to the more than human; a meeting point; a space in-between; a way of directing attention to earth others. It is a method of thinking with and feeling with’. The term ‘becoming-with’, which is central to Tuulikki’s conception of mimesis, is adopted from the writings of Donna Haraway, who uses it to evoke how human beings might enter into more self-conscious and empathetic modes of cognitive development alongside the non-human world. ‘To knot […] species together in encounter, in regard and respect’, Haraway notes, ‘is to enter the world of becoming with, where who and what are is precisely what is at stake’.2

Tuulikki’s awareness of the role of animal and non-human mimicry in global folk music and rituals is also key to consider here. There are many living cultural traditions wherein the human voice or musical instruments are used to imitate other species for a range of practical, creative or ritual purposes. For example, kulning is a form of Scandinavian vocalisation in which song is used to call livestock down from high mountain pastures; and the imitative effects of Tuvan throat singing, which is practised in Tuva and parts of Mongolia, can emulate the sound of a bird, river, cricket or horseback riding. Folk traditions provide the grammar of mimesis in much of Tuulikki’s work. She has toured with Scottish and European folk musicians, although she cites experimental vocalists, such as Meredith Monk, as similarly important references.

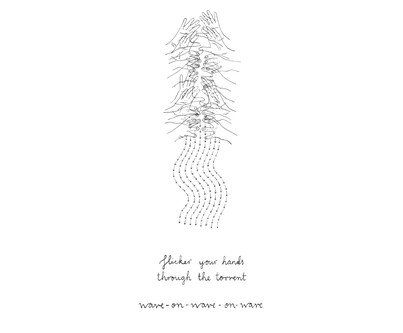

In 2016 Tuulikki undertook a month-long residency in Kochi, India, to develop a work for the 3rd Kochi-Muziris Biennale. There the artist began to realise the possibility of incorporating movement into her masquerade. She was introduced to Kapila Venu, a renowned practitioner of kutiyattam, a form of dramatic musical performance that involves storytelling through gestures of the hands and eyes. ‘Kapila taught me the Nadi Varnana, a sequence of codified gestures representing a river’, the artist recalls. Nurturing a ‘tacit knowledge of the kutiyattam tradition’, Tuulikki created SOURCEMOUTH : LIQUIDBODY (2016), a three-channel film and sound installation, which incorporates choreography, vocal composition, costume and a visual score FIG.6. She adapted the movements learnt from Venu into a trio of filmed performances: one utilising her body FIG.7, another her eyes FIG.8 and the third FIG.9 her mouth. In each, Tuulikki, with her body painted silver, traces the various stages of a river’s course from source to sea. In the first film, this is evoked through fluvial hand gestures; in the second, the camera focuses closely on her eyes as they perform dramatic movements that signify the same transition. In the final film, the artist’s disembodied mouth delivers a series of vocal incantations, which act as instructions for the bodily mimicry of the other two films: ‘take your eyes to the top of the high mountain, trace the summit with your fingers, open the brow, wait for the rain to fall’.

In establishing what would become long-running preoccupations with vocal and bodily mimesis respectively, Away with the birds and SOURCEMOUTH : LIQUIDBODY can be considered as pivotal works for Tuulikki. However, when compared to her current output, they arguably lack a certain quality of dissent or anger – of sounding the alarm call on the natural world’s demise. ‘My work has become more and more political since Deer Dancer’, she offers, ‘which is my first piece that engages with the ecological crisis directly’. Deer Dancer FIG.10 is a two-channel film and sound installation that incorporates visual elements such as graphic scores in the form of embossed and debossed prints. Premiering at Edinburgh Art Festival in 2019, it explores traditions of deer mimicry within global folk dances. Tuulikki is particularly interested in how the emulation of deer as a talisman for wildness has been used to codify and concretise certain elements of heteronormative masculinity. Often, these are bound up with a yearning for dominion over nature. Her source material ranges from the Deer Dance of the Yaqui people of Sonora, Mexico, to the Scottish Highland Fling and the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, which takes place every year in the titular village in Staffordshire.

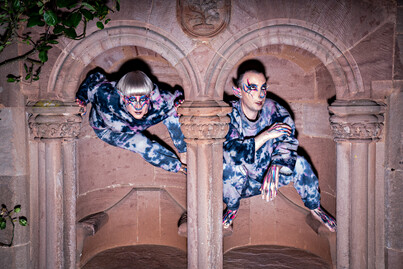

Inspired by these and other traditional choreographies, Tuulikki performed vocal and dance routines in drag-king-esque costumes that incorporated fake beards and armour FIG.11. Her scores, meanwhile, diagrammatise the steps of her dances, replacing footprints with gold-foiled hoofprints. Deer Dancer partly enacts a certain kind of masculine self-destructiveness, bound up with annihilation of the natural world. But Tuulikki’s embodiment of the animal – which also involved pitch-shifting her voice downwards – also constituted a kind of queering or détournement of such tropes. What comes across most strongly besides the piece’s eco-political aspects is a quality of burlesque or unbinding of gender binaries. This was pre-empted by Tuulikki’s 2016 homage to the mad Irish king Sweeney, cloud-cuckoo-island FIG.12. For this in-situ performance, the artist cavorted on a cliff-top on the Isle of Eigg wearing a mossy beard, offering up a strange high-pitched call to the sea in homage to Sweeney’s fabled mimicry of birds after his derangement in battle.

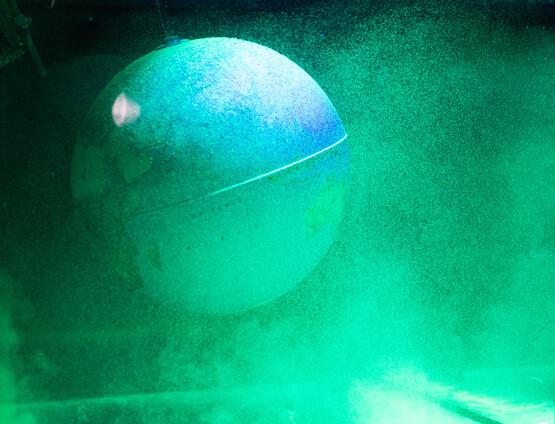

Tuulikki’s practice took another turn in 2022. An example is Echo in The Dark FIG.13, a silent rave behind Hospitalfield, Arbroath, during which audiences danced to music created from sonic approximations of bat echolocation calls. Here the artist and her collaborator Tommy Perman (b.1980) FIG.14 re-embraced their youthful love of 1990s rave culture, another touchstone she now mentions when talking about the ways in which musical cultures can foster empathetic engagement with other animals – in this case a heaving mass of human bodies. It is uncertain yet whether the artist will return to themes of rave culture; her current research includes the migration of the marsh warbler.

The ever-burgeoning value placed on Tuulikki’s work is inextricably linked to the increasing urgency of the climate crisis. This can be attributed in particular to the artist’s emphasis on the validity and value of our emotional response to such intractable, troubling themes. This approach does not reflect an anti-intellectualism, but rather an awareness that our own reactions and impressions carry within them forms of intelligence that have been sidelined by Western traditions wedded to linguistic enquiry, rational utilitarianism and human exceptionalism. As Tuulikki puts it, in a paraphrasing of the philosopher Timothy Morton, ‘we can’t think our way out of the ecological crisis. We have to feel our way. Tears are important. But radical hope, too’.3

Footnotes

- Unless otherwise stated all quotations are taken from a conversation between Hanna Tuulikki and the present author, 12th January 2024. footnote 1

- D. Haraway: When Species Meet, Minneapolis 2008, p.19, emphasis in original. footnote 2

- See T. Morton: ‘The end of the world has already happened’, BBC Radio 4 (2020), available at www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000cl67, accessed 3rd May 2024. footnote 3