Communist witches and cyborg magic: the emergence of queer, feminist, esoteric futurism

by Amy Hale • Article commission

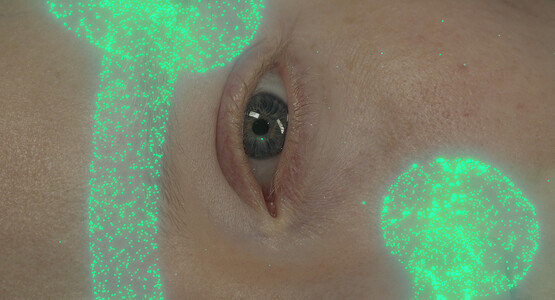

The meticulous processes of the New-York-based artist Felipe Baeza (b.1987) FIG.1 are closely linked to the concepts that he explores. Working across sculpture, collage, embroidery and painting, Baeza is particularly drawn to the materiality of paper, especially for its potential as both a physical and conceptual layering device. The artist’s interest in the mode of collaging stems, in part, from his own diasporic identity. Baeza lived in Mexico until he was seven years old, when he emigrated to the United States. The multifaceted nature of his practice mirrors the fragmented recollections of his childhood in Mexico and the spaces that he no longer inhabits. Many of his works include woven and loose threads FIG.2, alluding to experiences of relocation and the impact this has on memory. More broadly, they also reflect the universal experience of retracing events in different places at later points in time. In many ways, Baeza, by weaving disparate sources together, addresses the generative potential of reimagining the past as well as the inevitability of loss.

Baeza’s visual language verges on the surreal, addressing themes of queerness, the body, migration, histories of power, futurity and the natural world. His works are often rooted in an extensive archive of source material, which includes Mesoamerican and Catholic devotional images, photographs of pre-Columbian figurative stone vessels, anatomical and botanical studies and pornographic magazines. In recent works he presents the viewer with a fictive world in which hybrid bodies and mythical creatures are juxtaposed with natural elements. The artist defies categorical bounds, representing a simultaneous refusal and transcendence of the familiar, which evokes both fear and wonder and indicates a form of religious stupor. Raised as a Catholic, Baeza is well-acquainted with grandiose religious imagery, which often centres on the human body. In his sculptures and works on paper, he subverts such reference points and contexts, transforming bodies and re-envisioning their potential without confines.

Since he graduated from the MFA at Yale School of Art, New Haven, Baeza has exhibited in a number of major group exhibitions, including Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall at the Brooklyn Museum, New York (3rd May–8th December 2019) and The Milk of Dreams at the 59th Venice Biennale (23rd April–27th November 2022) FIG.3 FIG.4 FIG.5. He has already had five solo exhibitions, most recently Made into Being at Fortnight Institute, New York (8th September–9th October 2022) FIG.6 FIG.7, and his work has been acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Columbus Museum of Art and the San José Museum of Art. In June 2022 the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (GRI), awarded Baeza an artist residency as part of the 2022–23 Getty Scholars Program. Chiara Mannarino interviewed Baeza about the research he has undertaken thus far, as well as his recent participation in The Milk of Dreams and his plans for the future.

Chiara Mannarino (CM): What informs your choice of mediums and techniques?

Felipe Baeza (FB): The materials I work with, in part, are ones that I personally respond to and enjoy working with. On the other hand, I make decisions in order to conceptualise the ideas I’m working through. Another important note is my background in printmaking. Collage, for example, has allowed me to think about the possibility of combining different images and different times, bringing them into specific conversations and dialogues. Part of that is concealing things and foregrounding things. When I’m thinking of concealment, I’m thinking of masks. Masks hide parts of you away, but they also make visible new ways of navigating the world: this is the way collage functions in my studio practice.

CM: Your artistic process is quite labour intensive and, in my mind, imbued with care. Could you describe your approach to making?

FB: I appreciate your use of the word ‘care’. This, for me, reflects my commitment to the studio, what I create and how I approach it, which involves a process that is meticulous both materially and conceptually. Depending on the project I’m working on, my studio walls are usually filled with images and sketches that help me process ideas FIG.8. I often translate these thoughts into my sketchbook and from there move on to the different parts of making.

My large works on paper or smaller works on panel FIG.9 are more labour intensive. The paper I use to build figures often goes through a series of printmaking processes to create densely textured layers. When you’re looking closely at these works, you don’t really see brushstrokes, instead, you see my exacto knife at work. A lot of the paper elements are fragments of cut paper – sometimes they’re new, but often they’re scraps from different projects. The paper cut-outs have become another way for me to talk about fragmentation. It’s also about regeneration: using the same sources and materials that I have available to create these forms and these worlds.

CM: You also address a broad range of themes in your work – from the erotic to the religious. Where do these stem from?

FB: There are a variety of experiences that inspire my work, whether they’re connected to my childhood in Mexico, my teenage years in Chicago or more recent events and reference points, such as the work of my peers or contemporary writers. Also, as I’m living in the United States at the moment, I’m navigating certain socio-political contexts. All of these timeframes converge, helping me address concerns, such as how to reclaim a queer futurity that values difference over sameness, resists assimilation and embraces incompleteness.

CM: Can you speak a bit about growing up in Mexico and what it was like to come to Chicago at a young age? How did these life experiences impact you and, in turn, your work?

FB: I think there are two parts to this. The first is growing up in Mexico in a traditional religious family: I was exposed to, and fascinated by, Catholic imagery as a young child. Often, in each of my works, there is one central figure, and I think that this must be informed by the images that I grew up with, in which the body of the saint is its own landscape and there is no ground. The second is my reunion with my parents, who had already left Mexico for Chicago before me and my sister. Ideas of migration and the movement of people across borders has become integral to the ideas that I think about in my studio.

For a few years now, I’ve been incorporating foliage into my paintings, which is partly inspired by Mesoamerican mythology. According to certain myths, when you die, your body nourishes the soil and breeds new life. Plants are vessels through which your body can thrive even after death. My practice questions how we might thrive when the landscape is not there. I rarely include landscapes or settings in my work because sometimes the body is the only landscape that some of us have.

CM: You studied at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York, before undertaking the MFA at Yale. How did these educational experiences inform your career?

FB: These two institutions have been instrumental to my practice, although they were very different experiences. I moved to New York when I was eighteen and my time at Cooper Union was foundational in terms of my understanding of art history. It was also where I fell in love with printmaking, which I continue to take techniques from in my current paintings. Whereas, I was twenty-nine when I attended Yale, and I approached the two-year programme as a sort of residency. Yale posed a lot of challenges for me, but it was also where I developed my most meaningful relationships: I began working with Maureen Paley, who represents me, and Titus Kaphar (b.1976) was assigned as my core critic, who was instrumental in identifying the financial support I needed for my first museum acquisition. It was also the place where I met many people who are now my close friends. I think this is what both programmes have in common: my longest relationships are connected to my experiences in art school and I hold them close to me.

Another thing that stands out is that during the period between finishing at Cooper Union and arriving at Yale, I always had a full-time job, which, more often than not, was unconnected to art. But after Yale, I committed myself to my studio practice full time. It was the first opportunity I had to put in all my time and energy to create, research and process ideas in a meaningful way.

CM: You’re currently doing a residency at the GRI. Can you talk a bit about your work and research there?

FB: There are thirty-seven scholars across different departments and I’m the only visual artist. I was invited to participate as their artist in residence under the theme of ‘Art and Immigration’, one of the two subjects for this academic year. The residency includes a studio space at the GRI, with access to their resources, archive and collection. The fellowship also opens up many opportunities for dialogue with the other scholars in residence; it’s exciting to converse with peers across disciplines on issues related to migration, not only focusing on people but also ideas and objects. During my time here, I’ve primarily focused on an upcoming project with the Public Art Fund, tentatively titled Unruly Forms. I’ve been working on a series of paintings based on my research with Mesoamerican artefacts in museum collections across New York City, Chicago and Boston, reflecting on ways that these the removal and displacement of these objects has interrupted their original function, power and context.

CM: This year is full of residencies for you, as after the GRI you will be heading to the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass Village, Colorado, and then undertaking the Rauschenberg Residency on Captiva Island, Florida. Was this plan intentional? Did you feel that you needed time to make works without the pressure of immediately exhibiting them?

FB: It was more that things just fell into place this way. I was originally invited to do the Rauschenberg Residency in 2020, but this was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Then invitations from the GRI and the Anderson Ranch Arts Center followed. As my last long-term residency was in 2019, at NXTHVN, New Haven, it seemed right to go on this ‘residency tour’. I try to use these opportunities to pause and allow time for deeper exploration. Each residency offers unique opportunities, for example, the GRI has an abundance of research and archival materials. Residencies like Anderson Ranch and Rauschenberg offer access to facilities, such as a print shop or fabrication studios, all of which encourage new ways of thinking that might not happen otherwise.

CM: How do you hope these residencies will influence your work?

FB: I do think that I’m at an interesting point in my artistic journey. I’ve been exploring specific ideas conceptually and materially for a few years and I’m curious to see where else I can take them, but mainly I just want to keep this momentum going. If anything, I see myself evolving or building on this foundation to push my practice. On the other hand, I’m aware of my personal limits in certain disciplines and welcome opportunities to work with others. Recently, I collaborated on the production of the glass sculpture A self that is not quite here but always in process FIG.10, which was included in my solo exhibition at Fortnight. This widened my perspective of how a work can exist in the world. I’m always asking myself: how do I get out of this two-dimensional form? Do I need to? How does one make what I’ve been making into a three-dimensional form? What would that look like? I’m still navigating those questions, but this sculpture was an exciting start.

Another example is the publication Adiós a Calibán (2022), which is a series of collages. It’s exciting to see a body of work presented in this way, and to have people like Mary Miller, Director of the GRI, and Lauren Schell Dickens, Senior Curator at the San José Museum of Art, contextualise my work through their writing, so the goal for me is to continue to expand on these opportunities.

CM: Can you speak a bit about your recent participation in the exhibition at the 59th Venice Biennale?

FB: The selection of my work for the Venice Biennale was a complete surprise and very emotional for multiple reasons: I almost didn’t make the opening because of my immigration status. Participating in a major global exhibition like the Venice Biennale is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The impact it had on me – and for it to happen when it did – is hard to put into words. I’m still processing it. I remember I was coordinating my first studio visit with the curator, Cecilia Alemani, just days before the lockdown came into force, so we spoke over Zoom while I was in my apartment. Cecilia had just seen my solo show at the Mistake Room, Los Angeles, a month prior, and I felt that was important for her to know more about my studio practice. In terms of the exhibition, there are many things that are different being on a global stage: your studio receives more attention, you receive more invitations and you learn a lot throughout the process. I couldn’t have done it without the people working behind the scenes.

CM: What was it like to have your work exhibited alongside artists like Belkis Ayón (1967–99)?

FB: It was exciting to be in dialogue with Ayón and many other artists whose work I’ve followed over the years. She’s someone I have admired and a genius who we lost too soon. I can only imagine what she would have accomplished if she were still here. It’s always a joy to see her work in person, but particularly to see her work in such a prominent position at the Biennale.

CM: With the start of the pandemic, social justice movements, and other major global events, the past three years have led to many shifts in the art world, art landscape and in artmaking. How have you changed as an artist and how have you seen and experienced changes in the art world during this time?

FB: In terms of public, institutional changes, I’ve observed organisations expanding their resources or appointing people in roles who have historically been excluded. These are major accomplishments but they require continued support to ensure long-term impact. More personally, the first thought that comes to mind is just having a consistent studio practice, which, again, is relatively new and I want to keep leaning into it.