Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty

10.11.2021 • Reviews / Exhibition

The artist Elizabeth Neel (b.1975) FIG.1 lives and works in New York. She studied at Brown University, Providence, and at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, before graduating with an MFA from Columbia University, New York, in 2007. Since 2005 Neel has exhibited large-scale paintings and works on paper. The following conversation between the artist and Pia Gottschaller took place in late 2021, during the run of Neel’s solo exhibition, Limb after Limb at Pilar Corrias, London, which included new works painted during a period of national lockdown. Neel discusses her elaborate, finely honed painting technique, which includes using her fingers, rags, brushes, tape and print rollers; challenges that arise from oscillating between control and chaos; and why painting is comparable to writing a poem.

Pia Gottschaller (PG): The nine large paintings on display here were originally conceived for a nearby deconsecrated church, and although that plan didn’t come to pass due to COVID-19 contingencies, their titles, such as Eve FIG.2 or The Magda, still refer to this sacred context. The video documentary, also titled Limb after Limb, made by your brother Andrew for this occasion, gives viewers an idea of the incredibly wide range of images that you draw from, encompassing the abject, the beautiful and everything in between. You’re interested in medieval history as much as contemporary visual culture, and some of your main themes are death, decay, pain and redemption. There is also an immense variety of paint textures and compositional modes that I’ve never seen anywhere else and I’m interested in hearing how your themes and processes relate to each other. I find the works exude an almost overwhelming energy, but there is clearly also a lot of control in what you do. How do you balance being free and letting the paint do its thing with setting parameters so that you arrive at a visual result you’re happy with?

Elizabeth Neel (EN): My studio routine begins with priming my own canvas. This task-based activity gives me time for reflection because it’s repetitive and achievable. It can be meditative, which sets me up for managing all the incidents that occur in the process of making my work. The size I use is GAC 100 – it’s a clear product that leaves the canvas looking raw, but somewhat resistant to absorption, allowing paint to rest on the surface with a lot of texture and even pooling.

PG: Do you brush or roller it on? Do you prepare the canvas in any other way?

EN: I unroll a huge amount of canvas on the floor and apply two layers of the polymer with a sponge. I had to buy knee pads eventually because it’s tough on the knees. But it’s good, I listen to audio books while I’m priming. I’ll think to myself for example: ‘The biography of Caesar, this will get me through it!’. Once the canvas is dry, I tape off the edges. Because there is so much to manage visually in my paintings, I like the idea that there is a very clear limit or edge where the painting ends.

PG: In the documentary Limb after Limb that I just mentioned, in which we watch you paint some of the works in the exhibition, you say that the most terrifying thing is the edge of a work. Could you expand upon that?

EN: Yes, even though paint will bleed underneath the tape, there is always a line that designates the end. If I push a paint-covered roller across the tape there will be a tiny ridge that builds up between something and nothing. A painting has to acknowledge itself as a painting and that to me in part is about where it ends. There are artists who wrap their painting around the sides of the stretcher, but for me that’s a psychological thing I can’t handle. It makes me uncomfortable when everything is totally out of control, but it also makes me uncomfortable when everything is completely in control. It’s the navigation between these poles that creates dynamism within my work. Certainly, there are strategies that I stick to when I’m painting. I like creating things that feel like a performance or an event on a stage. Having all of this ‘raw’ canvas or unfilled area is like air, the medium that surrounds us FIG.3. When a painting gets too filled up, I retire it permanently; I throw it away. That’s a very difficult part of the process because there are times when the internal dialogue creates a lot of hand wringing and walking back and forth. I oscillate from thinking ‘Okay, I’m going to do this’ to being very irritated with myself for not wanting to sacrifice certain parts of the image to preserve the life of the whole. Eventually I attack it again and there’s a renovation period, and either the painting comes to fruition in a good way or it doesn’t. It can take many, many days, this method of arguing with the work. It’s a necessary struggle.

PG: One of the aspects that I find so compelling about your practice and in these paintings – in a similar way to Helen Frankenthaler’s, for example – is that your repertoire of tools and processes keeps evolving, which is led by the depth of your themes, from using a roller in a variety of ways to throwing paint or manipulating masking tape and paint with very experimental results.

EN: Working with acrylics instead of oils allows me to integrate more print-based techniques, which I really enjoy. It expands my vocabulary. Using rollers and monoprint techniques, folding and burnishing taped or masked areas means that I can’t stretch the works beforehand. These tools and techniques require a solid surface to press against.

PG: And how do you avoid getting an imprint of the floorboards or other textures like we see in some Frankenthaler works? Do you put anything underneath the canvas?

EN: While on the floor I work on top of cardboard and plastic, primarily because I can’t think if the floor gets too messy, but I don’t mind if unexpected texture comes through. It makes me think about fossils and gravestone rubbings. I try to use practical materials that are very commonplace and at hand, but use them in ways that they’re maybe not meant for. For example, interesting patterns result from applying waxed disposable palette sheets; because of the waxiness, they don’t really adhere to the paint or the canvas. The resulting effect is like frost on a pond, or a close-up image of a biological organ FIG.4. If you peel up the paper before a twelve-hour drying period then these kinds of edges aren’t as rigid. After I remove the wax paper I immediately aim fans at the canvas to dry it fast, allowing me to make my next move.

PG: What kind of paint did you use for the purple colour in Eve and Eve 2 FIG.5?

EN: I only use Golden Acrylics. That’s Permanent Violet Dark with a bit of Alizarin Crimson Hue mixed in.

PG: Never anything industrial?

EN: No, although during the pandemic there has been a worldwide shortage of primer and different paint colours – all sorts of materials are hard to come by. So, we’ll see what happens, maybe I will have to use other materials. At any rate, assuming that doesn’t happen, I sometimes use paint straight out of the container, but usually I’ll combine a couple of things with it in a way that’s not so complex that I can’t remember how to replicate it again. I’ll keep little samples so I can match if I need to. Certain colours tend to dry shiny and others dry matt. I like to let them do what they do chemically. I could use a matting agent for example but I don’t. I need to have a consistent head space for these bursts of activity and even though that can be episodic over a series of days, tinkering with formulas distracts from the narrative in my head and on the canvas.

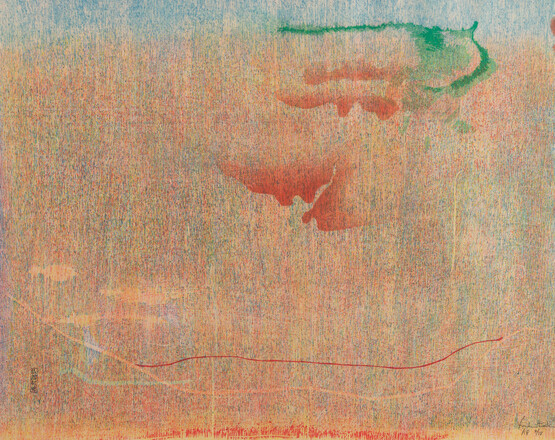

PG: So, the red shape in Deposal FIG.6 is straight acrylic paint, with nothing else mixed in?

EN: Yes. Water is the only thing I ever mix with the paint if I mix it at all. I use tomato sauce cans – they’re just the right size and if I put paint in, add water and scrunch it with my hand, it doesn’t mix fully. That gives me raw chunky texture. If I let it sit overnight and stir it the next day, I get a smooth texture. The more water I add the more transparent the paint gets.

PG: What role – if any – does chance play in the expansion of your vocabulary? Do you first envision a particular effect in paint because of what you have in mind and then find the tool that allows you to achieve it, or do you discover new painterly expressions directly through experimentation with new tools?

EN: Once in a while something happens unexpectedly, for example the palette sheet situation I described earlier. I’ll have an idea, I’ll try it, sometimes nothing interesting happens. I don’t go looking in the garage for strange tools or substances because I can’t typically justify that as part of my language. Robert Rauschenberg could drive over a piece of canvas or stick a chair or a bird to it and it made sense given his interests and critiques. For me making a painting is most similar to writing a poem. If you’re going to write it in a certain language, you only have a certain number of letters, which you can expand and reorganise. A roller may be a printmaking tool or a painting tool, however, to me it’s still part of my language. I need a certain level of consistency; I need to have an ongoing, intensive, even repetitive, conversation with what’s happening on the canvas surface. This requires an understanding of physics on a basic level: what gravity, centrifugal force and friction do to paint on fabric. I learn that by doing things over and over.

PG: There is a kinaesthetic dimension to your artmaking that keeps evolving similarly to how biological processes do. I make that analogy because of your interest in nature, in particular harking back to your growing up on a farm in Vermont. It’s stunning how many different textures you manage to create with a simple roller.

EN: Yes and it’s a process that is never separate from my body: it requires my activity and it’s also a record of my motion. The rollers I use to document movement – opaque swathes of jumping or jittery repeating shapes – are the same. They’re run-of-the-mill rubber rollers in various widths. You can get them anywhere, but they create just the right level of resistance. When the barrel rolls over other marks, sometimes a ghost of those marks will repeat FIG.7. Anything that happens like that visually, mirroring of the mystery of nature and the repetition of DNA, that’s wonderful. It’s an accident, but I always think of life as an accident, the most extraordinary accident. Little cells came out of a primordial soup and now we are where we are.

PG: There is sequence in the documentary in which the viewer sees you pour a large amount of paint. I imagine that it takes a lot of courage – perhaps more so at the beginning of your career – to work with expensive materials and not be able to make any corrections or changes after this process. Do you still have to work on being fully present when you do it or has it become a natural part of your flow?

EN: I have a battle with my own psychology, as people do. I have an internal conversation: ‘should this be thinner, should it be a different colour?’ or ‘did I go too close to this part?’. That being said, I’ve come to a place where anything that seems like a problem can also be food for the making process. I know more or less what tends to be productive, although I can’t always be sure. That initial pour is an exciting element because it’s a little scary and yet anything is still possible – the painting is just beginning. As I go through and build up and add, my options become more limited. Each decision becomes more important at that point. Whereas in the beginning, there’s a lot of latitude.

PG: That makes sense, yes, like in our lives, where certain options tend to narrow as we grow older. How do you keep your creative range as rich as possible?

EN: I tend to do this with tools: I’ll order one of everything, because maybe adding or removing a variable will complicate or simplify the equation in an interesting way. The other way I do this is to read or listen to literature as much as possible. The human story gets told and retold and speculated upon over and over again. I suppose that recycling connects me to the integration of life and art and gives it all meaning, which in turn gives me the energy and enthusiasm necessary to continue working.

PG: Do you remember a specific moment in the making of the works in Limb after Limb?

EN: For Stranger’s End FIG.8 I thought that the colours were going to be horrendous, and that the particular green was going to fight with the other colours. Sap green is fairly transparent and I tend to put yellows or ochres into it. But with this painting, because of the burnt sienna and those things underneath it, adding white to the green promised to create a lot of problems with the way the composition was functioning. So I thought, well, maybe doing the ‘wrong’ thing is the best thing to do here, and it ended up really working. I love it when that happens. Some paintings go along in progressive ways and then others require a near total loss. They all have their own personalities and experiential identities. Each one is its own poem in a way, its own performance.

PG: For the Eve paintings, at which stage did you fold the canvas to create this mirroring effect in paint, and how much do you switch between working on the floor and taking the canvas up to the wall?

EN: I go back and forth from the floor to the wall with every painting but I don’t stretch the canvas until the end. With Eve, the fold happened midway through. Folding always has to occur on the floor.

PG: In the documentary, you show the folding process with a small piece of canvas, which you’ve taped down so that you know exactly where the centre line is. With a painting like Eve, do you do the same: lay the support down and then decide in advance where you’re going to fold it and mark the folding line at the edges?

EN: I have to be very specific about it. Little differences, of millimetres, don’t matter because the canvas is always changing – because of the weather, for example – but establishing a level, a vertical and horizontal, is essential. Levels create a framework to hang gestures on but they also give the eye a point of comfortable reference in the turmoil – almost an x and y axis. When I laid down the initial parts of Eve 2, I put it up on the wall and immediately thought that I wanted something on the right side, not dead centre. If the fold is absolutely in the middle, it automatically reads as a Rorschach inkblot. That’s interesting in its own way, but it really becomes the dominant theme and the subject. I’ve made quite a few works using the central fold approach, but they’re really specific and they have a specific effect.

PG: In The Magda there is a magnetic blue shape on the left that could be a heart or a lung or angel wings FIG.9, while on the right a V-shaped pattern grows gradually fainter. How did it come about?

EN: This happens when the paint drips travel downwards and then as the roller passes across them it picks up just that line and repeats it over and over again. It’s so satisfying because the marks are uncanny, but essentially the action is simple. Painting is as joyful as it is gritty for me.

PG: There are a number of compositional elements in these paintings, where the surfaces look tufted, for example the orange wedges in Eve and Eve 2. The tiny, sharp peaks in the viscous paint look like something was pressed into it and then lifted.

EN: Yes, the viscous paint sticks to the roller and creates an almost hairy texture FIG.10. I tape the shape off, use a palette knife to fill in the area and then I drag a roller over it. This technique unifies the paint so that there are no palette knife marks or things that I find distracting for that kind of shape.

PG: When and why did you switch from oil paint to acrylic in your paintings?

EN: In 2014 I started using acrylics on canvas. I’d always worked with acrylics on paper. When I was wrangling with the compulsion to become a painter, with all the historical and personal reasons that seemed to advise against it, I thought of paper as portable and direct. I thought that I wouldn’t need a big studio, and could even work outside if the weather is nice. When I made the decision to paint seriously and applied to university in 2005, my application portfolio was mainly acrylic works on paper. For a long time after that, I thought that acrylic wouldn’t work on canvas for me. I was wrong. When I finally got the guts to focus and make a proper attempt it was so utterly freeing. I could make decisions in a space of continuity because of the quick drying time. With oil paint I use a lot of thinner to create washes and the fumes would make me sick and tired. The shift to acrylic paint made my life more interesting and content.

PG: Tell me a bit more about how you settled on the theme for the exhibition and how the context for the works’ display changed over time. There is an exacting beauty to the paintings and an expansiveness that testifies to your embrace of what the material will do.

EN: To me, they’re beautiful and also tragic. Because this work was initially made for a church, I was thinking about the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald and Nikolaus Hagenauer (1512–16) and the different ways its two sets of wings can be configured. I wondered how I could bring something of that to this project. The set up in the final room at the gallery reflects that interest FIG.11. Had the work been shown in a church those three pieces would have been in the apse. Instead of Jesus in the middle I have The Magda. Women’s roles in Christian mythology changed radically over time. These are so complex, contradictory and disruptive, but also elevating. I’m not interested in stressing a particular theme but I hope to inspire an evolving relationship with content and image. Paintings should be uncomfortable or even frustrating but also seductive. That’s how I feel about life and narratives in general.

PG: I think this sacral origin is still palpable and at the same time your imagery, wrought from your technique, transports it directly into our current period of pandemonium.