Thomas Demand: Mundo de Papel

by Lisa Stein

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 09.02.2022

Writing about his project In Scala (1977–78) – a series of photographs taken in a theme park in Rimini, which features scale models of such Italian landmarks as St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, and St Mark’s Square, Venice – the artist Luigi Ghirri suggested that ‘perhaps it’s in this very space, one of total fiction, that truth is concealed’.1 For Ghirri this artificial landscape, a ‘colossal photomontage’ spanning historical eras and geographical distances, was as real as any other: ‘it’s here and only here that on seeing St Peter’s dome, we do not refer back to the stylised images we have of it, but recognise the sham, and return to a perception of our own, seen in reality’.2 To Ghirri the theme park revealed a way of seeing that Susan Sontag, writing about photography two years earlier, referred to as a ‘grammar’ resulting from our need to ‘collect the world’.3 Although the photographs in which Ghirri chose to include the concrete paths and guard rails installed for tourists enhanced the surreal and absurd quality of the surrounding landmarks, it is the images in which he employed a more pictorial photographic language that complicate the difference between the ‘cliché, the copy and the stereotype’.4 If Ghirri’s image of the plaster model of Mont Blanc, for example, its black silhouette captured against the setting sun, could be mistaken for a photograph of the actual mountain, how would we determine which of the two images is a more accurate representation of reality?

The difference between original and reproduction has always been at stake in the work of Thomas Demand (b.1964), who began making small paper sculptures of everyday objects as a student in the early 1990s. Following the advice of his tutor, Demand began to use photography to record these objects before throwing them away, inadvertently creating narratives by capturing multiple sculptures in one image. Over time, the artist’s interest shifted from the objects to the photographs of them. Demand’s exhibition at Centro Botín, Santander, provides an accomplished overview of his transition from sculpture to photography and finally, to architecture. For the largest exhibition of his work in Spain to date, Demand has designed wallpaper installations and eight uniquely shaped pavilions FIG.1 FIG.2 to display some thirty large-scale photographs and a small number of stop-motion films made between 1996 and 2021. Suspended from the ceiling of the top-floor gallery, the pavilions, intended to simulate an ‘urban landscape’, mirror the design of Renzo Piano’s building, which hovers over the bay of Santander. Designed to ‘blend in completely’ with the surrounding Jardines de Pereda, which were subsequently remodelled and extended ‘to make the most of the building construction’, Centro Botín provides a suitable setting for Demand’s photographs of hyper-realistic full-scale paper and cardboard models, which consistently achieve an unsettling balance between the real and the artificial.5 In the early 2000s the artist also began to move beyond the traditional exhibition format by transforming gallery spaces with specially designed wallpapers, and the publication he has created to accompany this exhibition includes carefully crafted cardboard pop-ups that replicate the show’s eight pavilions.6

Although Demand is known primarily for his life-size reconstructions of vacant and at times bleak architectural spaces, such as, Zeichensaal (Drafting Room) FIG.3 and Lift (2005), his more recent work demonstrates an interest in the constructed natural environment. Upon entering the vast, light-filled gallery, viewers are confronted with the imposing installation Pond FIG.4. What initially appears to be a direct reference to Claude Monet’s Water Lilies – the photograph of numerous lily pads ‘floating’ on a dark blue surface has been mounted onto a concave wooden frame especially for the exhibition – is not a reproduction of the artist’s painting, his garden in Giverny, or the Japanese garden that inspired it. Rather, it is based on a recreation of Monet’s lily pond on Naoshima, a small island in Japan known for its collection of contemporary art. Demand has recreated scenes from nature to a painstaking degree before – for Clearing (2003) and Rasen (Lawn; 1998) he assembled thousands of individual paper leaves and blades of grass. However, Pond, a copy of a copy, is a more overt reference to the artificiality of landscaping as it has featured throughout the history of art and as part of present-day eco-architecture.

Demand also has a proclivity for recreating mass media images, in which the construction alluded to is not a material one. Folders FIG.5, for example, is based on a news photograph taken at Donald Trump’s first press conference after he was elected President of the United States, which he delivered standing next to a table supporting stacks of Manila folders. Trump famously claimed that the papers contained in the folders, which journalists were not allowed to consult at the time and have since been described as props, detailed his plans to distance himself from his business before starting work as President. While the photograph evokes Trump’s post-truth leadership, Demand’s work also gives new meaning to the former President’s concept of ‘alternative facts’ – the artist himself has spoken of the difference between ‘factual truth’, ‘fictional truth’ and ‘truthfulness’ in relation to his photographs.7 Junior Suite (2012), Demand’s recreation of a tabloid photograph of the table at which Whitney Houston dined on the night of her death, speaks to the fabrication of celebrity identities in the mainstream media. The photograph, which recalls the carefully arranged tables of Dutch still-life paintings, fills us, the viewer and consumer, with guilt and self-doubt, challenging our belief in the ‘reality’ of such images and how we fetishise objects that once belonged to musicians or actors (or artists).

Politically charged images have informed much of Demand’s work. Perhaps one of his most famous images, Badezimmer (Bathroom; 1997) is based on a 1987 photograph of the West German politician Uwe Barschel, taken after he was found dead in a hotel bathtub. Demand’s image is arguably more powerful than the black-and-white original, which includes Barschel’s fully clothed body, because Demand’s empty bathroom – still highly recognisable due to the angle the photograph is taken from – only hints at the events that unfolded in it. The circumstances of Barschel’s death remain controversial and Bathroom succinctly raises the question of how much we can know about the event from looking at the original photograph. Vault, a reconstruction of a photograph taken in a storeroom at the Wildenstein Institute, Paris, where in 2011 police discovered thirty works of art that belonged to the heirs of a Jewish family displaced during the Holocaust, is equally opaque. In Demand’s photograph, like in the image it is based on, the paintings, which included works by Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, are turned towards the walls, hidden from view. Whereas these works present a more overt challenge to photography’s claim to verisimilitude, Demand’s more light-hearted series Dailies FIG.6 FIG.7, based on photographs the artist takes with his smartphone, are suggestive of the changes in the way we take, share and encounter images, and how this in turn has affected the subject-matter of photographs circulating online today.

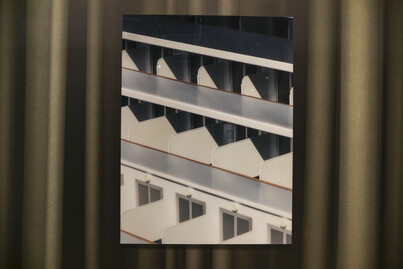

Conceived during the COVID-19 pandemic, Mundo de Papel also includes subtle hints at how lockdown restrictions impacted the way we experienced different spaces. Princess FIG.8, for example, was inspired by a cruise ship, held under a mandatory fourteen-day quarantine by Japanese officials, after several passengers were diagnosed with coronavirus in early 2020. Markise (Canopy) FIG.9 shows balconies in a block of flats, one of which has its canopy fully extended, alluding to the inhabitant(s) of this confined space – a reminder of the sense of isolation felt by many during the lockdowns implemented around the world. The individual pavilions that Demand has created, some of which barely allow for more than one or two visitors at a time, conjure up these feelings, the memory of which certainly enhances the sense of joy at being able to come together for such an exhibition.