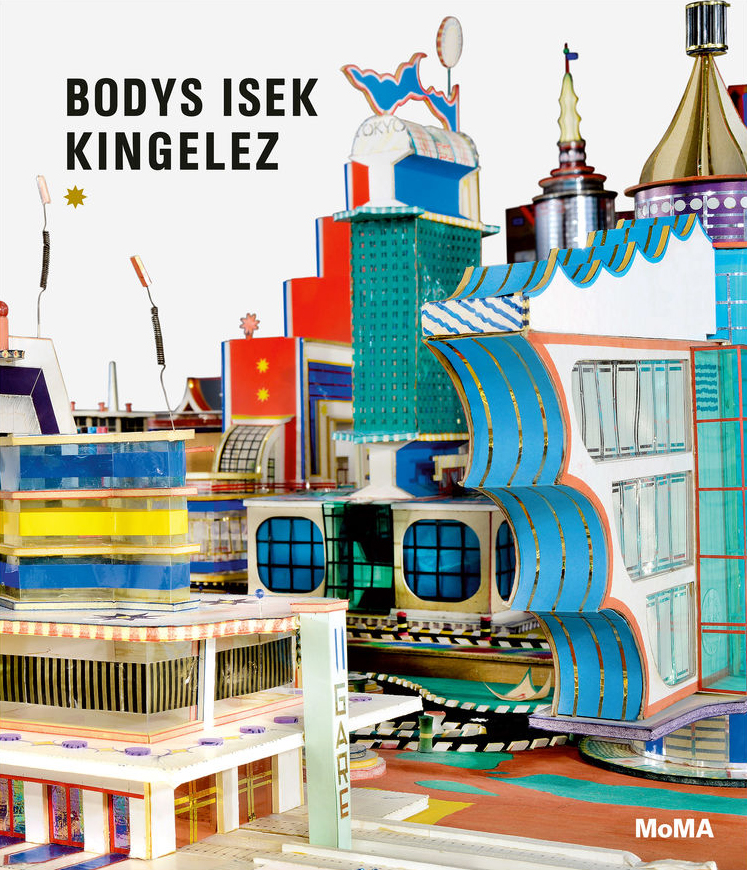

The enchanted world of Bodys Isek Kingelez

by Gauvin Alexander Bailey

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 01.10.2018

Many have been there: a down-at-heel resort hotel, conference centre or airport in a developing nation, built, in happier times, in a boldly optimistic style. Tropical colours abound, as do geometrically daring but dangerously teetering balconies and brise-soleils, concertina-style verandas now rusted and mouldy and sweeping walls of glazed white brick. Congolese artist and self-proclaimed ‘small god’ Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015) brings us back to one such buoyant moment in the 1970s, when Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) was poised to become the new cultural powerhouse in Sub-Saharan Africa and sponsored architecture to prove it. His miniature buildings and cities, which pack the punch of the real thing (Kingelez aptly called them extrêmes maquettes) were made with found materials, from fizzy drinks bottles to cigarette boxes and assembled with scissors, razors and glue. They emanate joy: the hope that buildings and urban spaces can bind people together and that a new beauty can be created through a fusion of global historical and contemporary styles. Few can look at them without glee.

Featuring thirty-three buildings and miniature cities this exhibition, curated by Sarah Suzuki, is the first full retrospective of Kingelez’s work in the United States and is accompanied by a handsomely illustrated catalogue. His creations are arranged on a series of low, white platforms to allow a bird’s-eye view. Visitors to the exhibition eagerly snap photos, bending down to focus on tiny details or kneeling on the floor to experience them at street level. Kingelez had no doubt about his work’s ability to enchant: ‘since time immemorial, no one has had a vision like this [. . .] I’m dreaming cities of peace’.1 Only art historians are confounded. His maquettes collapse time and cultures, adhere to no movement and defy categorisation as architecture, sculpture or design.

Nevertheless, Kingelez’s work does reflect his surroundings. Born in the then Belgian Congo, the artist moved from his home village to the new capital, Kinshasa, in 1970. There, President Mobutu Sese Seko was creating a visionary city on an altogether different scale, with a utopian suburb for foreign dignitaries called the Presidential Domain of Nsele. This project in urban planning, which V.S. Naipaul dismissed as resembling a luxury resort, came complete with gold-plated bathroom fixtures and a massive Chinese palace with cantilevered eaves, a landscaped garden and a pagoda. Other projects included the multilevel Palais des Bambous and the soaring, unfinished television tower, the Tour de l’échangeur. The Senegalese architect Pierre Goudiaby Atepa (b.1947) created tropical buildings for a ‘solar city’, notably his pyramidal Banque Centrale des États de l’Afrique de l’Ouest.

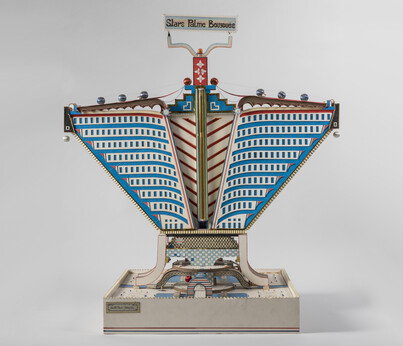

Kingelez drew deeply from the urban fabric of Kinshasa. His Stars Palme Bouygues FIG.1 turns Atepa’s Banque Centrale on its head, the structure perched precariously atop a terrace resembling a record turntable. The television tower makes several appearances, most directly in Approche de l’Échangeur de Limete Kin (1981), which is crowned by a pinnacle the original never had and rises from a base formed of grand chrome-plated loggias alternating with sloping walls bearing pictograph-like scrolls.

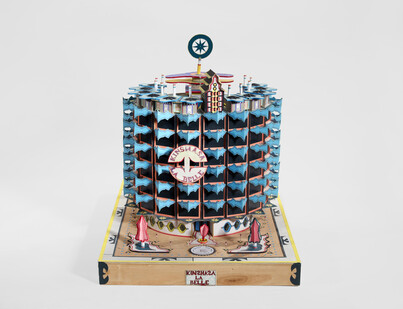

But most of Kingelez’s work derives from a world all his own, a spiritual ‘vision’ that came to him each time he began a maquette. Despite its name, the spectacular Paris Nouvel FIG.2 resembles the kind of hotels the Soviets used to build in Tashkent or Dushanbe, with its stars, radio towers, and colonnades – all in turquoise, yellow, pink and purple with polka dots. The round tower Kinshasa la Belle FIG.3 is like a 1970s Sheraton in Dar es Salaam with an encirclement of delicate blue butterfly-shaped balconies and brise-soleils, a clutch of rooftop pavilions and pink and green umbrella-stars. It even has a multi-storey car park.

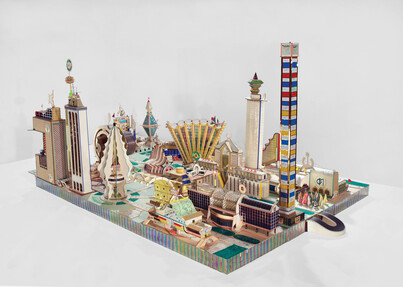

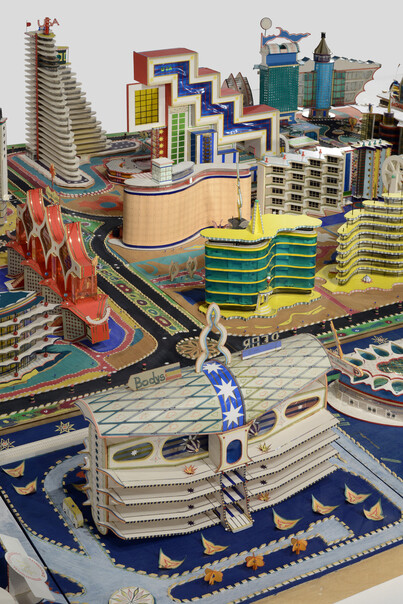

Kingelez’s most astonishing inventions are his full cities, with motorways, overpasses, bridges, stadiums, and petrol stations. Styles clash in harmonious irregularity. His Kimbembele Ihunga FIG.4, named after the village where he was born, includes an office building with a wave-like scalloped outer wall, a banana-yellow tower shaped like an open fan, a skyscraper straight out of 1980s Manhattan and a railway station that combines Las Vegas kitsch with Soviet provincial. One of the biggest of all is the Ville Fantôme FIG.5 in which towers from New York and Shanghai happily coexist with a scallop-edged, chocolate box-shaped ‘Aeroport Internationale’, and enough tropical resorts to populate a small Caribbean island. It even has an outer faubourg reached by the inauspiciously-named ‘Pont de la Mort’.

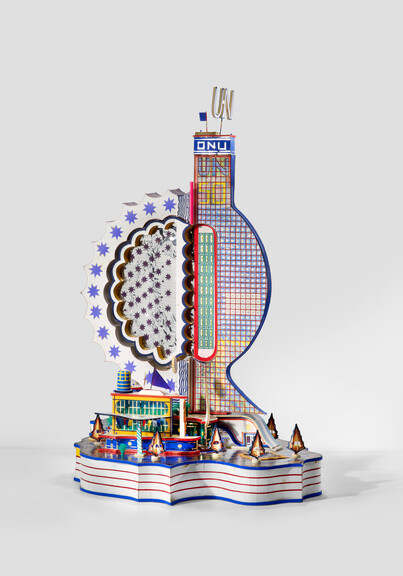

Kingelez’s patriotism is ecumenical: the Stars and Stripes stand next to Kremlin-style red stars; Zairian, German, Canadian and Belgian flags punctuate his work (he held no grudge against the Congo’s former colonial rulers); and his buildings display signs in a babel of languages. His peaceable kingdom is most overtly embodied in U.N. FIG.6, a roulette-wheel United Nations tower with pirouetting stars, rainbow rooftops, scalloped walls in deep purple with racing stripes and flags in appropriately neutral primary colours.

These buildings and cities have led many to call Kingelez a naïf. But he was a university-educated industrial designer, economist, and museum technician, spoke five languages and in later life travelled the world. He was also a prolific writer and philosopher, inventing new words and syntaxes (a ‘langage bodysois’ as he called it) as an extension of his art, much like Argentine painter Xul Solar (1887–1963) – who as it happened also designed space-age skyscraper cities, but only in two dimensions.

Playlist selected by Carsten Höller and Kristian Sjöblom

to accompany the exhibition