The Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art Museum

With the global rise of the contemporary art museum since the 1980s, an increasing number of modern and contemporary art historians have shifted their critical attention to the architecture of these spectacular storehouses of art. More often than not, scholars have approached such buildings with a good deal of suspicion, wary of what is considered to be their cheapening of the museum experience (albeit at great financial expense) and, as a result, of our encounter with the objects displayed within them. Terry Smith and Hal Foster, for example, have both drawn on theories of the supremacy of spatial over temporal experience in postmodernity, and a resulting consciousness that is unanchored from both past and future, to charge the contemporary art museum with the pursuit and privileging of a new ‘experiential intensity’ above all else.1 Their fear is that this may pose a mortal threat to older ideals of the museum as a space for the focused contemplation of works of art and for the cultivation of the spectator’s critical and historical cognisance.

There is much that remains persuasive about these arguments, yet it seems increasingly apparent that they overstate the salience of an antagonism between art and architecture that most would likely now consider outdated, or nominal at best. After all, the museum as ‘culture factory’ is the inevitable counterpart to contemporary art as a fully fledged creative industry. As Richard J. Williams states on the first page of this concise book, ‘institutions merely represent the priorities of the societies that produce them, so we get mainly what we deserve’ (p.1). Hence, the industrial scale and operation of today’s art museums, as nothing more or less than bourgeois outposts of what Williams identifies as society’s broader ‘entertainment complex’ (p.1), is not only our lot but also, more than ever, our expectation.

Through a series of case studies, Williams’s book skilfully demonstrates how changes in museum design have both reflected and propelled these developments, looking especially at how museum architecture over the past fifty years has often anticipated and thus, quite literally, prepared the ground for the industrialisation of art’s consumption. Indeed, Williams goes so far as to assert that it is largely on account of the prominence and popular impact of these buildings that today’s ‘expanded audience for contemporary art’ (p.66) has come to exist at all. Substantiating this claim, The Culture Factory takes the reader on an engaging tour of many of the most significant examples of museum architecture from the mid-twentieth to the early twenty-first century, to demonstrate its role in the emergence of art as merely ‘one point on a continuum of consumption’ (p.15) in the contemporary experience economy.

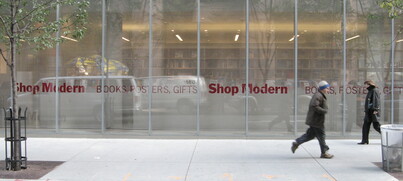

Many of Williams’s examples are already world famous: the ‘industrial imagination’ (p.19) of Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone’s Museum of Modern Art, New York FIG.1; Richard Rogers’s and Renzo Piano’s Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris FIG.2; and Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao FIG.3. Much of this territory will be overfamiliar to many readers, which, in many ways, is part of the book’s point. Williams’s argument proceeds from the observation that many such buildings nowadays – most obviously Guggenheim Bilbao but also, four decades before it, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York FIG.4 – are designed less for their suitability as vehicles for the display of art than for their potential currency as icons on a scale and ambition that far exceeds the resources and possibilities of any other artistic medium. It is, then, the contemporary icons of art museums that are the key ‘expressions of globalisation’ (p.71) of our era. For Williams (drawing on Foster), this amounts to the novel claim of the museum ‘as a form of contemporary art in its own right’ (p.14), a claim that exceeds conventional notions of architecture as a fine art and positions it as culturally pre-eminent, as ‘the authentic cultural form of big capital’ (p.11), to the extent that it ‘has displaced the very activity it ostensibly exists to show’ (p.116).

Williams’s disarming assertion that the rise of the contemporary art museum as architectural icon spells the end of ‘art’s exceptionalism’ (p.9), and that the most globally significant art of our time therefore ‘entirely [lacks] the critical dimension we [have] come to expect from contemporary art’ (p.72), will surely be difficult for any art historian to square with his dispassionate claim that The Culture Factory is ‘not a regretful book’ (p.9). After all, one would think that the social value of art history must be premised on a commitment to the possibility of art’s ongoing capacity for resistance to the capitalist sensorium. Williams’s sights, however, are firmly set on a future that the global pre-eminence of architecture-as-art may now be steadily bringing into view. For Williams, contemporary museum architecture allows us to glimpse a future in which the critical tradition of Modernism may come to be revealed as a historical anomaly, and in which the residual traces of resistance that the contemporary art of today inherits from the movement are revealed more and more as the quaint vestiges of a bygone era. In such a future, the suspicions of Foster, Smith and others would certainly prove well-founded, yet whatever sense of historical loss or regret is still perceptible today – and still channelled by such authors – may have finally receded.

The Culture Factory concludes with an examination of the diffuse ‘art zones’ (p.114) of New York’s High Line FIG.5 and Beijing’s 798 Art District FIG.6, spaces that Williams argues are the clearest auguries of this future, and that ‘define an emergent global sensibility about the consumption of contemporary art’ (p.96), characterised by ‘amiable wandering in [. . . locations] defined by “art-ness”’ (p.96). We may yet discern the autonomous works of art that still populate these ‘generalised art landscape[s]’ (p.97); for Williams, however, their significance within them has become uncertain. Art is not merely displaced in these environments, but is very possibly ‘brought [. . .] to the point of dissolution as a meaningful category’ (p.116). At the very least, as the ‘quasi-public’ (p.113) spaces of the museum and art zone increasingly bleed and disappear into one another, and as we ‘drift from one spectacle to another’ (p.114) in such spaces, art’s own distinction within such a terrain is becoming ever harder to determine. Against the author’s wishes, perhaps, many are likely to find cause for regret within these pages.