A Countervailing Theory, a parable

22.12.2020 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Beth Bramich

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 25.06.2021

Rehearsing identity can move us towards a practice of radical self-love. It can also move us further away. All depends on who is in charge of the script. Although some may claim that education is apolitical, our understanding of ourselves in relation to our peers, communities, society and the world are indelibly shaped by what we listen to and repeat. First in schools, and then through popular culture, we come to understand ourselves. Naturally, we look for people like us in the stories we are told, and are informed by how those who share characteristics such as gender, race, sexuality and ethnicity are treated and perceived.

In terms of well-rehearsed stories, the Nativity is a classic. In most schools in the United Kingdom the nativity play is an annual Christmas event. Britain may be a notionally secular nation and we may go to notionally secular schools but ours is a Christian culture; the lines between church and state exist more like a braid than a boundary. The Nativity – the birth of Jesus Christ, son of God, King of Kings – is performed perennially and it is us who act it out: blonde angels, shepherds in tea-towels, kings bringing gold, frankincense and myrrh. Each rehearsal of this Christian story, whether we are given any lines or not, affirms its cultural values and beliefs in our lives. We learn, repeat, manifest, honour and obey.

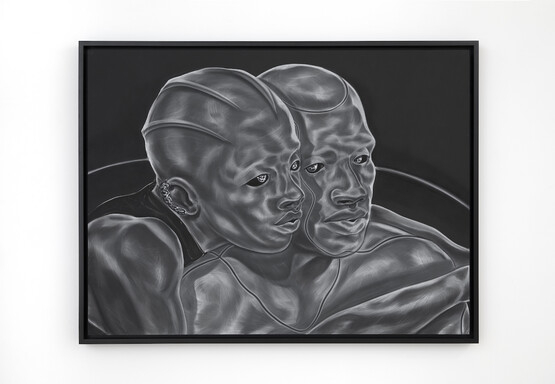

In her school nativity, Rosa-Johan Uddoh was selected to be a king. This was a formative casting, her first performance as a Black British person, playing the only non-white role in the primary school play. A teacher cast Uddoh as Balthazar, a King said to represent Africa, who gave the gift of myrrh to Jesus. The Magi first appeared in depictions of the Nativity from the medieval period onwards and became individualised in the early fifteenth century, when one was identified as a Black man and given the name Balthazar. In Uddoh’s solo exhibition Practice Makes Perfect, the Magus, in all his finery, takes centre stage. For her large-scale, gold-backed collage Breaking Point, Uddoh found approximately one hundred and fifty Balthazars in Adoration paintings made throughout European history FIG.1 and collated them into a visual fanfare FIG.2. His gowns and trims are sumptuous and he greets himself in many guises, some more Eastern, ‘Oriental’ or African. Hung on either side, on unfurled scrolls like scripture, are texts written by Uddoh FIG.3. Here, she writes about Balthazar and her role in the nativity, inviting the viewer to walk in between, to observe his expressions, gestures, interactions, and to imagine the unnamed Black models who posed for this role FIG.4.

And here is the truth that Uddoh draws attention to. In her work, we find an early history of Europe – specifically Britain – that is not solely white. This history is one of multiple colonial powers, of countries building empires through invasion, oppression and displacement of others. In our systems of learning, we are told that Britain beat a path of ‘discovery’ through a wilderness – that prior to our landing there was no culture, tradition, society or knowledge. Moreover, this narrative erases the presence and contributions of Black people in Britain prior to an imperial invitation in 1948, when in June the HMT Empire Windrush arrived in the United Kingdom from Kingston, Jamaica. Subsequently, the boat became a symbol of multicultural modern Britain, an origin point for inaccurate scholarship of Black British history.

Breaking Point depicts hundreds of Black people, who were painted centuries before, as the artist puts it, a ‘bloody big boat’ docked at the Port of Tilbury, Essex. These depictions however, render them tokenised people. Without fail, Balthazar is subjugated in relation to a white baby: he kneels as King of Africa to show Jesus’s power and prove Christianity’s dominance. Using scale and theatrical tropes, Uddoh has humanised him by focusing our attention on each model in turn. Her immersive collage and accompanying narrative set them on a joyous parade, returning agency to these citizens of major European cities. She imagines for us a little of what their lives and experiences were like – how with whatever they had to hand, in a tired old get-up and for a fee, they would consent to take up this role, to ‘do the nativity’.

Balthazar, although generally not referred to by name, is still one of the few Black people of importance who one is likely to encounter in primary education in the United Kingdom. In March 2021 the government’s commission on racial and ethnic disparity released the Sewell report, which was commissioned by the Prime Minister following the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. Its investigation into our education system found no evidence of institutional racism in policy or practice, instead it found the United Kingdom to be a model of racial equality. The report was met with anger and frustration. As activist groups campaigned for and worked towards new curriculums, which would address the absences and erasures in our education that are foundational to the perpetuation of racism, this report stated that this was unnecessary. Uddoh cites the Black Curriculum, Black Blossoms and the Free Black University alongside her own long-term research as the impetus for the works in this exhibition, which point to the glaring omissions of Black British history.

Shown winding on a scroll across the front of Focal Point Gallery, WINDRUSH: A TONGUE TWISTER is inspired by the British love of the tongue twister. Uddoh contrasts the act of mastery over something that is difficult to say – Peter picked a pepper, a peck of pickled peppers – with British institutions, who over the last year in particular have found it difficult to speak to their own day-to-day and structural racism FIG.5. One line asks ‘And if black Britain began before that bloody big boat / Why won’t sir say so?’. In her video Practice Makes Perfect, the printed text is twisted into new shapes by a group of Year 8 pupils from a local school in Southend-on-Sea FIG.6. They turn it into a set of sketches and competitive tasks, performing for the camera as if starring in their own TV show FIG.7. Uddoh’s words become the basis of play as the group test new words, stretching the syllables of ‘colon–ia–lism’ and picketing the education secretary with placards and speeches calling for more and better food, more free periods and time to be creative. In editing the film, Uddoh and collaborator Louis Brown turn the group’s play into a reality, with the addition of graphics, jingles and comedy cuts to camera for reaction shots – the whole thing credited to the school group as Chicken Nuggie Productions.

Shown next to this is the video Brown Paper Envelope Test, which stems from another significant educational experience: exam results day. Holding sway over her future, a brown envelope is comically enlarged and suspended over Uddoh allowing her to clamber up and peer into it FIG.8, while her mother, played by the actor Josephine Melville, looks on, eager to find out whether her daughter will succeed in life. Uddoh combines this familiar period of waiting with popular science data, using DNA results to represent the general public in a list of countries of origin FIG.9 FIG.10. The title of the work frames this mini-drama in reference to Nella Laren’s 1929 novel Passing, written during the Harlem Renaissance, when the ‘Brown Paper Bag Test’ was employed as a door policy by night clubs to refuse entry to those whose skin was darker than a brown paper bag.

There is a type of self-love that representation enables. For those who do not see themselves in the histories they are taught or in popular media, such as Black British people, it is instead an exclusion from culture and an absence of respect for their value and humanity. But there is also harm inflicted on those who see themselves and their cultures, which are built on oppression and exploitation, represented too generously. In her book Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent, Priyamvada Gopal highlights that a history in which elite white men of the West led humankind towards freedom inevitably presents the rest of the world as passive beneficiaries of white rule. This understanding of history, which remains part of British mentality, pretends that there was no anti-colonial resistance that was not borne out of imperial gifts; no possibility of freedom or self-determination outside of capitalist terms; and that the ultimate goal of empire was always to reward suitably developed and enlightened nations with self-government – a conquering to liberate primitive peoples. Gopal’s book tells the stories of anti-colonial actions and movements led by colonised peoples that have shaped British conceptions of nation and freedom. She demonstrates that a willful ignorance and attempted erasure of these histories continues to underscore British, American and NATO neoliberal foreign policy, particularly under the banner of wars of liberation.1

The denial of our cultural heritage leads us on into a blinkered future. To introduce WINDRUSH: A TONGUE TWISTER, Uddoh quotes from Stuart Hall:

Britain’s relations with the peoples of the Caribbean and the Indian sub-continent does not, of course, belong to and begin in the 1940s. British attitudes to the ex-colonial subject peoples of a former time cannot be charted from the appearance of a black proletariat in Birmingham or Bradford in the 1950s. These relations have been central themes in the formation of Britain’s material prosperity and dominance, as they are now central themes in English culture and in popular ideologies. That story should not indeed require to be rehearsed.2

This absent history, before and after the arrival of the Windrush generation, is a massive loss to all who do not learn it. Black British history did not start and end with the arrival of a bloody big boat.

Practice Makes Perfect marks a shift for Uddoh – not only in terms of scale as her first institutional solo show or in a move away from her past live performances or performances to camera. Here, we also see her working in pursuit of self-fulfilment and wish fulfilment through her practice. Drawing on Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic (1978) and Poetry is Not a Luxury (1985), this work is about a radical self-love that considers not what roles she is asked to perform but those that she wants to rehearse. In this is a desire for self-expression, not to take on responsibility for representing others but instead find a way to speak clearly and honestly in order to resonate with them. Through this expression she invites the audience and her participants to consider what parts they want to play.

Rosa-Johan Uddoh: Practice Makes Perfect

Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea

19th May–29th August 2021