Peter Friedl: Report 1964–2022

by Claire Koron Elat

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 30.03.2022

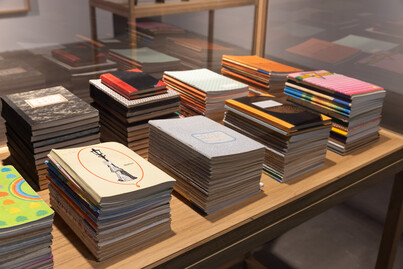

In a diary entry for 23rd March 1914 Franz Kafka notes his yearning to be wholly elusive: ‘I never wish to be easily defined. I’d rather float over other people’s minds as something strictly fluid and non-perceivable; more like a transparent, paradoxically iridescent creature rather than an actual person’.1 Kafka’s desire to be non-perceivable appears to be obliterated, however, by our access to his innermost thoughts, as provided by the publication of his diaries. Report 1964–2022, a retrospective of work by Peter Friedl (b.1960) at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, begins with the Austrian artist’s own diaries. The Diaries FIG.1 comprises hundreds of notebooks in different colours, which are meticulously stacked and sealed in three glass vitrines. According to the exhibition material, each handwritten page covers one day of the artist’s life from the last forty years. In an act that resembles the paradoxical experience of reading Kafka’s private plea for imperceptibility, Friedl leaves himself simultaneously exposed and unexposed. Any inspection of the diaries is physically close yet cognitively distanced, since not even the exhibition curators have been given access to their contents. The Diaries are afforded the status of an architectural or sculptural medium.

This exhibition is the most comprehensive institutional survey of Friedl’s work in Germany to date. It brings together works spanning five decades, encompassing video, sculpture, textiles, installation and drawings FIG.2, revealing Friedl’s life-long interest in alternative modes of narration, historiography and language. Report 1964–2022 is shown across three spaces and covers the trajectory of his practice – from small, early works to more recent, large-scale installations. Shown behind The Diaries is New Kurdish Flag (1994–2001) FIG.3, a pale pink, semi-transparent piece of fabric with a central circle cut-out detail. The textile is a distorted version of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party flag, which features a star enclosed in a circle on a deep red background. This work is a testament to Friedl’s interplay of political and formal concerns, evidencing the artist’s process of simultaneously referencing and obscuring information.

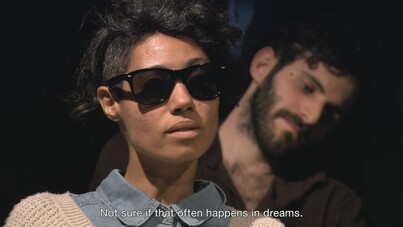

Friedl’s practice often negotiates sociopolitical issues through theatrical modes of presentation. In the twenty-eight-minute film Study for Social Dreaming FIG.4, the artist invited participants to share their dreams in a public group session guided by two psychologists. The work is loosely based on W. Gordon Lawrence’s notion of ‘social dreaming’, which postulates that dreams are products of cultural knowledge and therefore, in part, anthropological documents.2 Social dreaming places the focus on the dream rather than the dreamer, and examines the crucial social and political roles they can play when shared. One might expect these non-private dimensions to become transparent in Friedl’s work as participants disclose their dreams in a public setting but individual narratives are disrupted by the artist’s decision to use a non-chronological form of storytelling. As utilised in The Diaries, Friedl’s mode of narration is one in which a personal form of disclosure takes place in an obscured framework. Although he makes intimacies public, or pseudo public, they remain impenetrable. Recalling Kafka’s yearning, they demand to be perceived as being non-perceivable.

Direct references to Kafka appear in one of Friedl’s most important works, Report FIG.5, after which the exhibition is titled. The film is projected onto a large wall in the centre of KW’s main hall. Filmed in the National Theatre in Athens, it shows twenty-four performers as they recite from Kafka’s short story A Report to an Academy (1917). The text takes the form of a lecture delivered by an ape named Red Peter, who has learned to behave like a human. The actors, mainly amateurs, perform either in their native language or a preferred one, including Kurdish, Dari, Greek, English and French. German, the original language of Kafka’s story, is intentionally left out. The work, which was first presented at documenta 14 in Athens in 2017, investigates the interplay between language, identity and historiography. Although many of the actors had only recently arrived in Greece as refugees, Friedl does not explicitly address these political contexts. The performers, who have all left their respective countries, are not unified by language but instead by gestures, physical presence and their new home in Athens. Moreover, by omitting subtitles, there is an additional narrative displacement and the audience must also seek common ground outside of language.

In her book Nox (2010) the poet Anne Carson noted that the word ‘mute’ is ‘regarded by linguists as an onomatopoeic formation referring not to silence but to a certain fundamental opacity of human being, which likes to show the truth by allowing to be seen hiding’.3 In Friedl’s work, this opacity is annexed rather than nullified. His diaries, which are visible through the transparent glass of the vitrines, are there to be seen, albeit in a diffuse way. Where things were previously unknown or unimaginable, they become, at the very most, imaginable through opaque forms of narration. Despite this, Friedl’s works are in no way silent; there is always a subject that tells us about the existence of their interiority FIG.6.

Friedl’s interest in the simultaneous desire for hyper-visibility and privacy can be applied and extended beyond visual art. A number of fashion brands, including Balenciaga and The Row, are deliberately retrograding to a form of understated exclusivity through concealment. In 2021, for example, the Italian fashion house Bottega Veneta deleted its social media presence, including its Instagram, Facebook and Twitter accounts.4 A year later it launched an app with an AR feature, which allowed users to watch video documentation of the Winter collection projected onto their own surroundings. In a manner that recalls Friedl’s obfuscation, the brand intended to stimulate their consumers’ imagination by transitioning from extreme visibility to a controlled and deliberate obscurity. Although Bottega Veneta claim the move aimed to expand and diversify the possibilities for interaction and conversation with the brand, it is ostensibly a commercial one with a product or object to sell. The object in Friedl’s work, however, remains obscured.

The artist’s work Rehousing FIG.7 FIG.8 comprises twelve scale model reproductions of historical – sometimes destroyed or never realised – houses. These include a replica of the philosopher Martin Heidegger’s cabin in the Black Forest, Ho Chi Minh’s former private residence in Hanoi and an eighteenth-century slave hut on the Evergreen plantation in Louisiana. The miniatures operate on a formal dilution similar to New Kurdish Flag. The flag’s history as a symbol of resistance has been obscured because of its missing and manipulated characteristics; here, the reduction of scale in Rehousing obliterates the houses’ original function. Like The Diaries, they are perceivable only from the outside, whereas the point of both houses and diaries is to provide access to what they contain. While Friedl’s work is a form of bringing people together, he also employs tools that exclude. He assembles domesticities, interiorities, dreams and wishes as a way of presenting and exposing an opaque form of living.