New Order: Art, Product, Image, 1976–95

by Sacha Craddock

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 06.09.2019

Named after the band with whom the designer Peter Saville is so persistently linked, New Order at Sprüth Magers, London, is a spare exhibition that surveys a range of approaches to class and place in British art between 1976 and 1995.1 Upstairs, watercolours by Richard Hamilton carry the superficial gloss of an Andrex advertisement, morphed with the flow and shift of Cézanne colouring to create something quite other FIG.1. Hamilton’s elaborate printing method, typical of work he made at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, was characterised by a combination of reproduced imagery and product placement. Two other works by the artist carry a level of physical exactitude, with collaged aluminium foil used to describe the top of a machine in Study for ‘Lux 50’-V11 (1976), while a squat and shiny Diab DS-101 computer FIG.2, which once belonged to the artist, is displayed on a low plinth, having become a work of art only when it stopped functioning. Hamilton’s perception of the role of technology and design surpassed any Pop idealisation of mass production in order to integrate touch, sight and surface into a hidden and increasingly dematerialised presence. Such a telling combination of materiality and invisibility is part, after all, of an exhibition in which all work has been made in the pre-digital world.

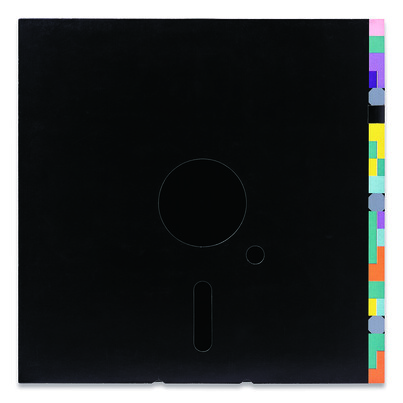

Rather than taking a linear approach to his subtle realignment of history, the exhibition’s curator, Michael Bracewell, allows a skip and jump across the surface of the exhibition, to bring the album cover for Blue Monday by New Order into a new context. The record sleeve, designed by Saville in 1983, is displayed in a vitrine FIG.3. With its limited palette and calm assurance, the cover is typical of the designer’s particular graphic approach. His ability to culturally embolden a buying public – and to provide a sense of glamour – is underestimated insists Bracewell. Saville, who is so knowledgable about art history, brought a sophisticated sense of touch, finish and framing to a fixed format: ‘I had the freedom’, he wrote, ‘to quote from the canon of art and design that I had begun to discover in the library at Manchester Polytechnic, rather than in the reality of my everyday existence’.2

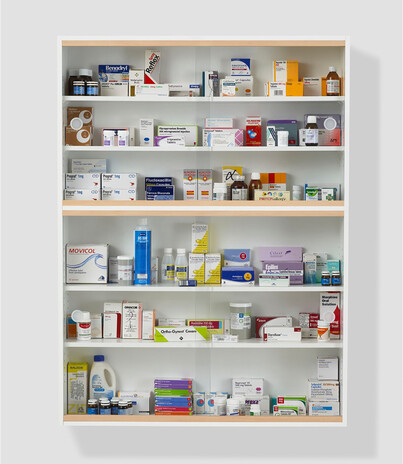

Saville’s object of design and desire lies directly across from Damien Hirst’s Satellite FIG.4, a glass-fronted cabinet of methodically displayed packages of pills and ointments. The medicine, sitting square, is presented in much the same way as a melon or vegetable in a painting by Luis Meléndez. Although these ordered objects do not add up to any sort of personal narrative, they point towards a familiar, if generally hidden, part of everyday life. While Saville engages with the persistently confused relation between art and mass production by merging music with surface, design and function, Hirst addresses the same question very differently, armed with a sort of end-of-the-pier attempt at gravitas.

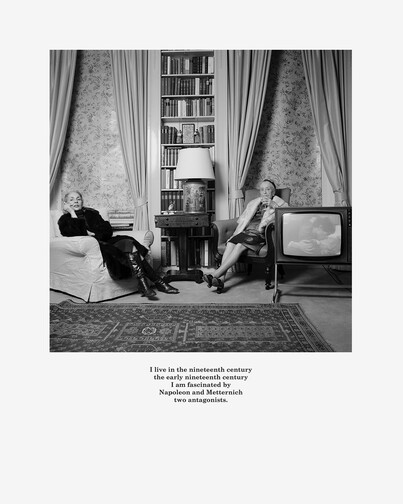

Belgravia (1979–81), Karen Knorr’s series of pictures of rich people, is a revelation. It is an early example of the photographer’s very mannered approach to her subjects, and combines text and image in true 1980s-fashion. The wealthy, staged and still, and are photographed deadpan FIG.5: in front of a fireplace; lying on a bed; and in other strangely amorphous and impersonal places. A woman in a puffy taffeta dress is photographed against patterned wallpaper, while a young man, in bowtie and pale jacket, sitting in a good Modern chair in front of mock-Georgian fitted furniture is coupled with the text, ‘There is nothing wrong with privilege, as long as you are ready to pay for it’. The implication, of course, is that the person speaking is the one photographed.

Early films by the Young British Artists downstairs are the unwitting products of their time, the eventual conclusion of Thatcher’s new England. Four old-fashioned video monitors face the street on the ground floor FIG.6. In one film Angus Fairhurst is running on empty, making something out of nothing: jumping with great force and deliberateness, over and over again. Filmed in black and white, it is low-tech and apparently simple. He is dressed in a gorilla suit stuffed with newspaper, which falls out as he jumps about the empty space. As he does so, elbows appear, followed by a bum, and then a whole naked body, released from the suit. The modernist principle of using what comes to hand combines here with student poverty, allowing beauty, somehow, to creep in.

The other films share this theatrical low-fi aesthetic: Hirst and Fairhurst are dressed as clowns, doing their Peter Cook and Dudley Moore impression: ‘now is the end, the end of the world, oh OK, same time next week’; Gary Hume talks of King Cnut in a bath wearing a Burger King cardboard crown FIG.7; and Sam Taylor-Johnson’s Brontosaurus, which plays a different game altogether, documenting in slow motion a young man’s performance in a corner of a room, near a radiator, the movement of his flaccid penis out of time with the music. Dressed up or naked, this real generation of friends (albeit a somewhat over-constructed myth) is making do, open in terms of expectation and finish.

Downstairs, on a huge screen, Gillian Wearing’s Dancing in Peckham is a dare as to what is viable in art. With no market, no name, the film combines a public, everyday setting with durational performance to provide the necessary level of formal discipline. Generational shifts affect the perception and reception of these works: Wearing, Fairhurst and Hume are represented by early work, and although they eventually demanded a substantial market (or had a market forced upon them), it certainly did not look like they would at the time. With an off-hand questioning of value and worth, the work came out of an irreverential fight against artistic pasts, the heaviness of the 1970s and subject-matter of the 1980s. The people photographed (and caricatured) by Knorr, however, are members of the newly unaccountable and international ‘no such thing as society’ society. Upstairs, in Hamilton’s pastiches, and to a different extent Hirst’s formal gravitas, an artistic lineage is presented, from Cezanne, through Watteau, to the sculptural readymade.

The photographs of London punks taken by Olivier Richon and Karen Knorr are a little less engaging and function here to provide a link between culture, music, representation and fashion. While the Young Artists show themselves to be rough, funny and Beckettian, the punks photographed are projecting a more polished surface. Bracewell writes in the accompanying booklet about a line of artistic greatness, from Hamilton to Hirst through Saville, aiming to define and recontextualise British art in terms of weight and function, from apparently off-hand scraps of film to Great Art upstairs. Although an art-historical lineage may be sought, the actual experience of the exhibition provides something quite other, and better.