Jesse Darling and The Ballad of St Jerome

by Rey Conquer

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 28.11.2018

The stories of saints are difficult because they show us that things can be otherwise. This is often quite literal: a wild lion can become tame, as in the story of St Jerome; a rich man can become poor (Francis, among many others); a woman can become a man (Marina, Euphrosyne, Theodora). Ideas of purpose are upturned: a hand becomes a nest for a blackbird (Kevin); a lion wears the harness made for the donkey it has been accused of killing, and faithfully carries out the donkey’s work as punishment for a crime it did not commit (Jerome, again). Such stories run counter to ideas of measure or order; they expose the fragility of worldly structures and institutions, including the Church; they show by exaggeration how much of what is taken for granted as necessary for a good life is in fact the material accretion of a decadent and impoverished culture.

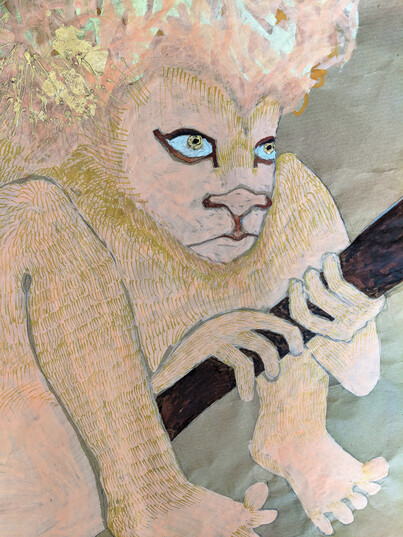

Sanctity and its modes – incongruity, reversal, excess – are the motor for Jesse Darling’s show at Tate Britain, London, the latest in its ‘Art Now’ series. Darling, who lives and works in London and Berlin, has brought together a number of ideas that have surfaced in the artist’s previous work, such as human frailty and vulnerability, as well as the force of ritualised or religious practices (Darling has stated an interest in what they suggestively call ‘liturgical devices’). St Jerome is there in the title, although the show is really a call for the canonisation of the wounded lion he is said to have greeted and instructed his terrified brothers to heal FIG.1. There are icons featuring the anti- or semi-saints of Icarus and Batman. And an accompanying booklet contains the correspondence between Darling and the Anglican priest Tina Beardsley, in which they discuss the discomfort provoked by the stories of certain Christian saints, particularly women who seem to have died ‘more or less because of structural violence’, but also those, such as St Gemma Galgani (1878–1903), who might now be considered ‘crazy rather than holy’.

In the course of this correspondence, Darling comes across one of the FAQs posted on the website of an Anglo-Catholic church, which justifies its statues of saints and angels by referring to the saying, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. Throughout the exchange Darling returns to this idea, which, given the familiarity of the cliché, forms a compelling crystallisation of the ideas underpinning much of the work on view. The many thousand words of the booklet form an important counter to the claim that the show might be iconoclastic in any sense: it is here that Darling sets out what it is they think pictures can do (make things right), and it is also here that it becomes clear that the presence of Christian imagery in the show is not for the purpose of mockery or elegy. Moreover, this wordiness is in productive contrast with the way the sculptures and drawings bypass language and are open to every and any sort of attention. On Darling’s Instagram the image descriptions, which are usually intended as an accessibility measure for those who use screen readers, become a new kind of exegetical form. Titles also do a lot of work. In an art-historical joke, two of the works are called ‘temporary reliefs’, which seems to take seriously the consolation and focus that icons (understood both as religious images and as works of art) can provide. A series of skittish-looking museum vitrines filled with ring binders, cast concrete and model birds, whose spindly steel legs buckle beneath them, is called Epistemologies FIG.2. In its pointed use of academic jargon, however, this second joke strikes a false note in a show otherwise remarkable in the way it manages to be both unapproachable – many of the works are literally spiky, made of toilet brushes or sharp-edged aluminium foil FIG.3, while its palette of clinical pinks and greys might be considered unappealing, even ugly – and, at the same time, stubbornly ‘accessible’. This is not to say that the works are straightforward or obvious, rather that they are immediate, difficult but not abstruse.

Throughout the show there are wounded hands, some robotic with tangled, disconnected wires FIG.4, their index fingers in sheaths or splints. These injuries recall St Isaac Jogues (1607–46), who was granted a papal dispensation to allow him to celebrate the Mass despite not being able to hold the consecrated host in the manner that was then stipulated, since his thumb and forefinger had been lost through torture. Darling’s sculptural hands, while visibly impaired, do things: they hold, point, make signs in BSL, write. One of the lions flanking the entrance, for instance, rests its pawless wire leg on a novelty pen resembling an amputated finger, a jokey detail that is nevertheless tender towards things considered pitiable or discomfiting. The Asemic writing of Correspondence is shaky; the lines of holes drilled into the mobility-cane trees are wobbly. What, the show repeatedly asks, is the minimum competence required for performance, creation or communication?

At first Darling saw the story of St Jerome and the lion as a kind of love fable — the lion’s ‘woundedness’ recognised in the face of fear and aversion – but worried increasingly about the subsequent dependency, the taming, and began to see Jerome as a representative of institutional control, the exercise of sovereignty ‘in gloved hands’ by the Church, Museum or Academy. Jerome, then, is Tate Britain, and here is the exhibition, the wall text for which, in claiming that Darling ‘explores identity’, names a certain kind of woundedness and tames it.

It is telling that the wall text does acknowledge the obvious subversion of the gallery-as-institution seen in Epistemologies: it is an easy gesture of self-critique. By framing the show in this way, the Tate has neutralised the questions that Darling is posing, namely the atomisation of vulnerability, where identity is used as an instrument of taxonomy and isolation that is handed out as a crutch that one seems to have to use. Many of the works can function as a modern memento mori: illness and disability will come for us all. Thus, vulnerability, like sanctity, may seem the ultimate ‘equal opportunity’. But vulnerability particularises: individuals, even individual parts of a person or body, are threatened and affected unequally. How can we take this into account, and how do we make use of the tools and prostheses at our disposal, while mounting a defence against being reduced to them? (How, in other words, does one resist one’s vulnerability being turned into one’s brand?) And can art, which Darling sees as religion’s successor, provide people with a visual vocabulary for imagining such a defence? These are important and ambitious concerns, and the show is, as a result, dense and challenging, unsparing in the demands it makes on our attention, but unsparing also in its kindness.