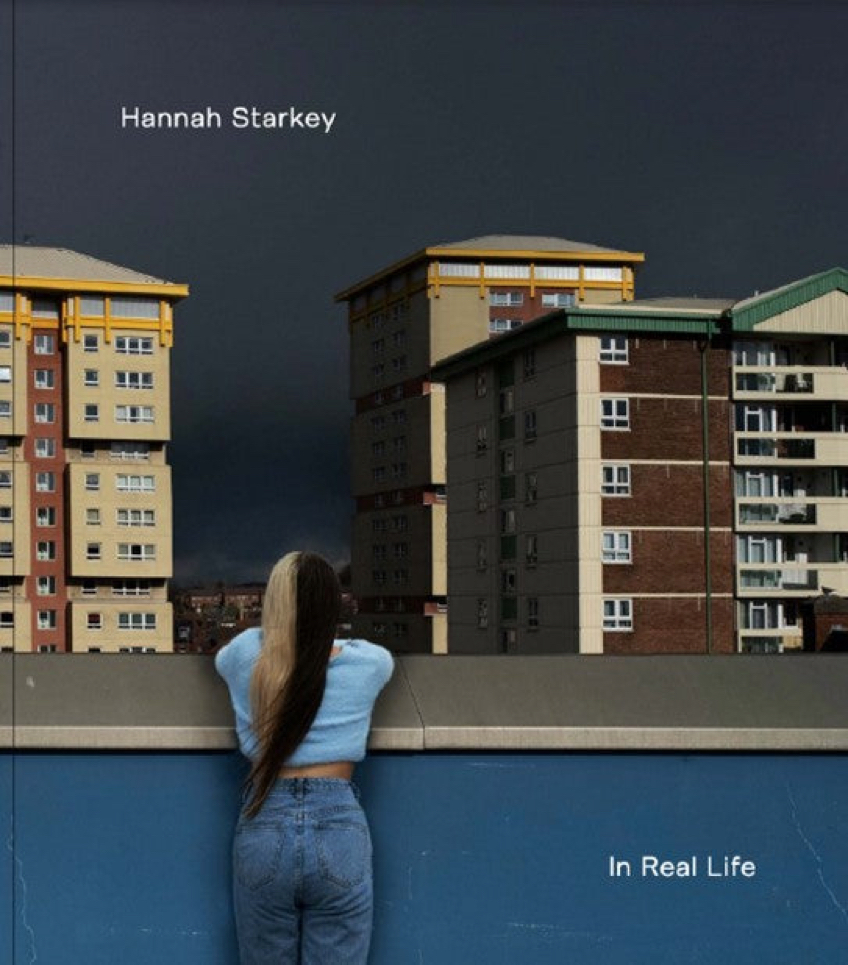

In Real Life: Hannah Starkey’s staged photographs

by Margaret Iversen

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 29.03.2023

Staged photography has proved to be a remarkably productive genre for female artists, who use models, architecture, lighting, props, clothes, gestures and photographic techniques to explore the constructed nature of female identity. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977–80) are early examples of staged scenarios that raise questions about the status of women in contemporary society. Although Hannah Starkey (b.1971) is certainly part of this photographic tradition, she does not – like Sherman and other exponents of the so-called ‘pictures generation’ – use film and advertising imagery as source material for her photographs. Nor is she interested in the postmodernist practice of deskilling and critiquing traditional notions of artistic originality by appropriating and reproducing images already circulating in the world. Rather, she sets up scenarios based on incidents that she has encountered in the street or public spaces. She shows women out and about in the city; domestic scenes are conspicuous by their absence. Her scenes are not fictional, they are found. Her large-scale, colourful and quasi-narrative photographs are cinematic and, in this respect, have much in common with those in the ‘directorial mode’ by such artists as Jeff Wall (b.1946), Philip-Lorca diCorcia (b.1951) and Gregory Crewdson (b.1962).

Starkey’s focus on found subjects is signalled by the title of her exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield: In Real Life suggests an effort to cut through the layers of mediation that so fascinated her predecessors. The abbreviation of the phrase, IRL, took on new resonance during the COVID-19 pandemic when meetings, events, classes and even parties were forced online. Starkey’s commitment to ‘real life’ has an impact on her choice of subject-matter and her approach to photography as a medium. Wary of exercising too much control over the image, she devises ways of allowing chance, the inadvertent incident, to enter the work. Commenting on a number of her photographs from the late 1990s to the 2000s in an interview with the philosopher Diarmuid Costello, she noted that these photographs of women in ‘controlled and sterile’ public spaces with hard-edged interiors ‘strive for perfection’.1 The look of flawlessness is further enhanced by digital post-production techniques and by favouring rectilinear compositions. Yet, these women seem uncomfortable or withdrawn; they somehow fail to conform to the spaces of corporate modernism. This dissonance, she says, ‘disturbs the controlled nature of the image’.2

An example of this strategy can be seen in some of the photographs on display in the exhibition. Newsroom, 2005 FIG.1 was made in the wake of 9/11 and the 7/7 London bombings. A woman is seated in an icy blue television studio and is surrounded by banks of spotlights, cameras and monitors. As the wall caption informs us, she is being interviewed about the traumatic events that she has witnessed. Her gesture, lowered gaze and the vividness of her red top suggest that the interview may be retraumatising. Other examples of uncomfortable women in alien environments were staged in a dentist’s waiting room (The Dentist, 2003) and the UBS reception lobby in London (Untitled, August 2006).

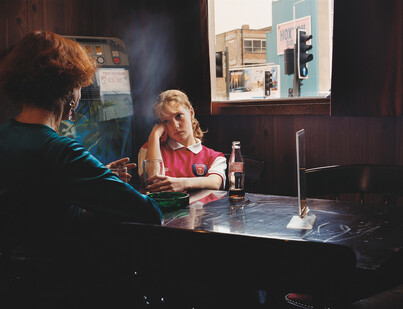

Starkey also disturbs the controlled nature of the image by including details that the viewer might at first overlook. Discussing this practice, she refers to the photograph Untitled, October 1998 FIG.2, which shows two women in a pub – an adolescent girl and older woman – and points out three disruptive details: the disgruntled girl wears an Arsenal shirt; the Coca-Cola bottle is strangely alluring; and the older woman wears a crystal earring that captures the scene.3 She could also have mentioned the uncontrollable cigarette smoke, which features here and in several other photographs. For Starkey, these features have an effect akin to Barthes’s punctum: a detail in a photograph that touches the viewer. As she put it, these points of connection ‘can seem like insignificant details that the photographer wouldn’t have bothered considering but was simply part of the scene’.4

The women in Starkey’s photographs who inhabit contemporary corporate buildings appear to be under societal demands to conform. Their failure to do so therefore conveys the hope that they might be able to preserve a sense of themselves, representing a point of resistance against the dominant culture. Recently, Starkey has become particularly interested in exploring sociopolitical conditions for prepubescent and teenage girls, who are subject to pressures in the form of fashion, advertising, music videos and social media: they live in a world full of seductive pictures – ‘perfect images’ – designed to make them feel inadequate.5 This new focus is prompted by the artist’s experiences of raising two daughters and becoming acutely aware of how teenage girls absorb the prevailing visual culture and try to emulate its ideas.

For example, Untitled, March 2022 FIG.3 shows two young teenage girls standing in front of a series of mirrors, the effect of which is vertiginous, multiplying everyone in the space to infinity. The figure on the left, who sports a heart-shaped patch on her cheek, is helping her friend apply make-up. Initially, she seems to be the dominant figure in the scene, until one notices that she is out of focus, and that, although the friend’s face is turned away from the camera, her reflection looks directly at us. As Starkey has made clear, it is not so much the external image as the ‘inner workings’ of her subjects that interests her (p.118).6 Scrutinising the mirror-image, one understands that the girl is receiving a heart-shaped mark to match her friend’s. It is also just possible to make out the photographer’s hand and her finger pressing the camera’s shutter release button. The scene, bathed in pink light, is ambiguous. Although the viewer empathises with the girls’ shared experience, one also laments their internalisation of an ideal of femininity promulgated by a misogynist visual culture.7 A shocking photograph commissioned for the exhibition FIG.4 appears to reference the extreme damage such ideas can cause: a young woman seated in a café props her head up on an arm covered in scars left by self-harming. The photograph is an updated version of one taken over twenty years ago FIG.5, which similarly shows a woman gazing out of the window, however her arms do not carry such scars. The development of the image – from the isolation of teenage years to something much darker – speaks to ‘the mental health crisis fomented by social media and the mechanisms required to support young women’ (p.10).

One room of the exhibition FIG.6 is devoted to works that mark a shift in Starkey’s practice. On 21st January 2017 Starkey joined the Women’s March in London FIG.7, which, like those in Washington and many other cities, was held the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration and was prompted by his misogynistic rhetoric and policy decisions that threatened women’s rights, such as proposing a large number of Supreme Court candidates who oppose legal abortion. These images – although they are carefully framed and digitally manipulated by combining details from different photographs – have more in common with documentary than staged photography. Often showing the backs of heads, they were taken from the viewpoint of participants in the crowds and are formally less composed. These images of defiant and joyful women are a far cry from the constrained, uncomfortable and solitary women of the earlier work.

Although Starkey’s photography has always been concerned with the position of women, her work has recently taken on a greater sense of urgency. She has become increasingly concerned with the ways that her own medium is used for creating and circulating stereotypical conceptions of womanhood aimed at selling commodities. She responds to this in a variety of ways, one of which is her series of portrait-like photographs of women and mothers with their children. A particularly striking example, Untitled, February 2013 FIG.8, shows a woman, who Starkey notes is a single mother, with a small child striding across a snow-covered field in a park. The woman carries her grocery shopping bags slung over a pole balanced on her shoulders. Shot from a low angle, the woman seems monumental, towering above the buildings in the background. It is a picture of this individual’s resilience under the pressures of single parenthood. This ‘portrait’ series and the vibrant protest images succeed particularly well in achieving Starkey’s stated aim of ‘changing the value system of what is beautiful’. As she put it herself, ‘this is real life and it is also beautiful’.8