Lee Lozano: Strike

26.04.2023 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Helena Reckitt

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 26.03.2019

‘Do You KEEP thinking THERE MUST BE ANOTHER WAY’, asks a hand-drawn text fragment in one of Emma Talbot’s floor-to-ceiling paintings on silk, 21st Century Sleepwalk FIG.1. Turning a nondescript corridor into an exuberant portal, Talbot’s paintings set the exhibition’s tone of feverish uncertainty. Diaristic quotes mix with silhouetted female forms who climb and reach, topple and fall, in a game resembling snakes and ladders FIG.2. Combining the obsessive repetitions of outsider art with science fiction’s hallucinogenic tone, Talbot’s abstracted plant and bird forms hint at ecological crisis and connection.

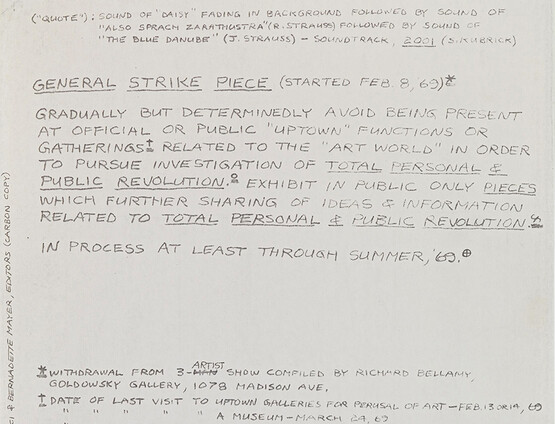

Acts of resistance and withdrawal are explored throughout the exhibition at Mimosa House, London, which takes Talbot’s question as its title. Lee Lozano’s 1971 decision to boycott women looms large over the show’s conceptualisation, although its physical presence – a facsimile from a page in her notebook – is slight. Announced shortly after Lozano withdrew from the art world, her choice to stop communicating with women lasted for the rest of her life and included relations with her mother. While Lozano did not conform to expectations of feminist solidarity and refused to participate in collective actions of the time, her determined questioning of obligatory consensus can be understood in feminist terms, as Jo Applin argues in her insightful monograph Lee Lozano: Not Working (2018).

Querying the terms by which dominant institutions accept marginalised subjects informs another key work, Howardena Pindell’s video Free, White and 21 (1980) FIG.3. Covering and uncovering her face with assorted bandages and cosmetics, Pindell plays two characters: ‘herself’, an African American artist narrating her lifelong experience of racism, and the white woman from the video’s title, for which Pindell dons sunglasses and a blonde wig. While dismissing her accounts of racism as paranoid and ungrateful, the white woman outlines the steps Pindell needs to take if she wants to gain mainstream acceptance. ‘You have to use symbols that are valid if we are to validate you. Otherwise we’ll find other tokens’.

These poles of inclusion and withdrawal play out in Raju Rage’s Under/Valued Energetic Economy (2017 and ongoing). The installation’s title is inspired by the work of the African American writer and activist Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and presents Rage’s work on self and collective care among that of other artists, scholars and militants. Centred around a fabric mind map that reflects the collective knowledge generated over kitchen table conversations FIG.4, the installation encompasses ephemera, publications and audio recordings FIG.5. Surviving Art School: An Artist of Colour Tool Kit, written by members of Collective Creativity, the QTIPOC (Queer, Trans* Intersex People of Colour) artist group, includes poignant letters of encouragement to their younger selves. Kyla Harris’s 2017 Self Care Manifesto, printed on an apron, conveys advice both serious and playful. ‘Always keep a book, a scarf, a water bottle and nuts on you. Unless you’re allergic. Then no nuts’. Listing acts of refusal as well as pleasure, Sophie Chapman’s and Kerri Jefferis’s Extraction October relates to their month-long effort in 2017 to protect their energies and resources, and avoid (self) exploitation. Like Pindell, Rage is sceptical about how established groups appropriate marginalised identities and neutralise them in the process. A poster by TextaQueen sardonically celebrates ‘The Circus of the Oppressed’, where ‘Minority Artists Bring the Political Heat Yet Contain the Flame within the Frame; a sweatshirt by Rage hanging on the wall reads ‘NOT YOUR QTPOC CELEBRITY’, made with temporary medical stitching.

The expectation that artists perform versions of themselves on demand is challenged in Georgia Sagri’s Documentary of Behavioural Currencies / Georgia Sagri as GEORGIA SAGRI (still without being paid as an actress) (2016). We see the artist attempting to renegotiate her contract with Manifesta 11, which includes the stipulation that she is filmed for a documentary for no additional pay or creative credit. ‘It’s about artistic integrity’, she explains to the baffled biennial staff, whose faces and voices are rendered anonymous. ‘This is my content and my intellect, acting the artist’. Alongside the original Manifesta contract, Sagri presents her two proposed (unaccepted) alternatives. Both acknowledge and remunerate her labour, in one as an ‘actress’, in the other an ‘artist’.

The Mexican feminist art group Polvo de Gallina Negra (Black Hen Powder), formed by Maris Bustamente and Mónica Mayer in 1983, use humorous intervention to question and transgress social norms. Two videos of 1987 show the artists as guests on popular daytime television shows. In one, they discuss myths and realities of motherhood with the prim female host while their young children cavort about the studio. Viewers are invited to phone in to discuss motherhood, and to send candid letters addressed to their own mothers to the museum. In the second show, a pregnant Bustamente dresses the patronising male anchor in a pregnancy apron and crown and administers him pills, in order to give him insights into expectant motherhood FIG.6. While the studio audience sniggers at this temporary disruption, the host reassures them: ‘after a break, the macho of this programme will return’.

Historical research becomes manifest in Georgia Horgan’s exquisitely tailored costumes on mannequins FIG.7. The clothes are embroidered with phrases denoting women’s class and moral status, drawn from Ferrante Pallavicino’s novella The Whore's Rhetorick (1683) and a recent essay about prostitution and dress. They are accompanied by a digital response to Pallavicino’s book, in the form of a script for a speculative film, which is viewable on an iPad in the gallery and a website commissioned by Mimosa House. While so much written material is hard to digest in a single gallery visit, Horgan nonetheless compellingly evokes how the regulations of gender and class, obscenity and eroticism have played out in the sex work and textile industries. The prevalence of textiles in the exhibition, together with video and print, points to a counter-history of feminist aesthetics.

Highlighting tensions between classification and control, subversion and strike, the exhibition asks who and what dominant systems routinely include and exclude, and on what terms. Urgent, funny, and unapologetically didactic, the exhibition stages a dialogue between – as well as with – feminisms past and present in order to imagine how things might be otherwise.