We, a part of them: Laura Anderson Barbata and the disassembly of border regimes

by Madeline Murphy Turner

by Edward J. Sullivan

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 18.06.2021

Dedicated to showcasing art by Puerto Rican and Latin American artists and artists of Latin American and Caribbean descent working in the United States, El Museo del Barrio has long played a crucial role in the New York art scene. Beginning in 1999 the biennial exhibition The (S) Files charted the course of what was then popularly known as ‘Latino’ art. After a number of successful editions and changes in the museum’s direction, the series ended in 2013 and has now been replaced by a triennial. Its first iteration bears the title Estamos Bien (We Are OK).1 Its preparations were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and a number of the pieces by the forty-two participating artists and collectives deal with themes relating to chaos, destruction and, in some cases, the ravages of the disease itself.

This engaging exhibition takes its name from a work that was prompted by one of the most cataclysmic natural disasters of the last decade. The Brooklyn-based painter Candida Alvarez created the two-sided banner-like work Estoy Bien (I am OK) in 2017 FIG.1, in the wake of a personal and a collective tragedy: the death of the artist’s father and the devastation caused by Hurricane Maria, which shattered life and land in Alvarez’s ancestral island of Puerto Rico. An ironic declaration of the artist’s stoicism and self-awareness, this work suggested to the three curators – Rodrigo Maura, Susanna V. Temkin and Elia Alba – a title that would indicate both the strength of contemporary movements in Latinx art and the self-reliance of practitioners working across a diverse range of media.

The artists in Estamos Bien are from a variety of backgrounds: many were born in the United States to families of Caribbean or Latin American origin whereas others arrived as immigrants from Central and South America. They all embrace the recently derived term Latinx, in which the ‘x’ renders the formerly standard denomination of ethnicity, Latino, as gender-neutral. The term now has broad currency and Latinx art is enjoying serious scholarly and popular interest.2

The Triennial does not hesitate to proclaim the many politically and socially engaged points of view shown within it. In this respect, it is reminiscent of some of the most outstanding, and controversial, Whitney Biennials of the 1990s. As to be expected from an exhibition of topical art, Estamos Bien charts many common thematic trends, both political and subjective. The consequences of colonialism and enslavement manifest foremost as leitmotifs. How could this be otherwise in an exhibition that mines, even implicitly, the history of the western hemisphere? Further subjects include migration, terror at the southern United States border, the ravages of Trump-era policies and the depredations of capitalism run amok. The wreckage on the collective health, psyche and economy by the actions of Big Pharma constituted one potent example of this abuse of power, as seen in the work of the Los Angeles artist and queer activist Joey Terrill. Family ties, often strained by the consequences of immigration and exile, the importance of food as a means of bonding in Latinx communities, queer sensibility and queer aesthetics are also among the most noticeable connecting threads in the show.

The curation of the Triennial was an immense challenge, compounded by isolation and distancing of all kinds. The museum undertook a series of ‘Think Tanks’ in 2019 and 2020 that included curators, artists, scholars and critics to form the core ideas of the exhibition. Alba also held a remote ‘Supper Club’ as part of her artistic practice – the results of which are revealed in the ‘In Conversation: Identity, Race, and Trauma’ chapter of the catalogue. The publication is also valuable for its work descriptions, and the ‘Reader’ section at the end, in which key texts on Latinx art are republished. The use of text in the show is also thought-provoking; introductory wall texts of the overarching themes and goals confront the viewer only as they are halfway through their visit. The labels for individual pieces are admirable in that they clearly lay out the concepts of each piece while also suggesting multiple meanings.

For her work Mammy Was Here: dirty?detox-bareMinerals, the Chicago-born, Haitian-raised artist Dominique Duroseau creates a series of poignant dramas with her own body FIG.2. In the performance, photographed by the artist, Duroseau’s nude form moves in dialogue with a mask and beads; a checked cloth entangled with the artist’s hair recalls the garments worn by enslaved persons. All of these elements indicate, as she explains in her catalogue text ‘abstract narratives: a raconteur telling tales of racism, misogyny, sexism through minimal imagery, micro-gestures. Interrogating racism and eroticism simultaneously’ (p.123). Although it was not possible to stage the performance Monument I by the Cuban, New-York-based artist Carlos Martiel with an audience, the video documentation carries an almost-equally potent impact FIG.3. The artist stands silently on a white plinth, his nude body is covered with blood. Capturing the monumentality of his silent stance, the work suggests stoic abjection in the face of physical and psychological abuse suffered by people of colour.

An accumulation of elements, the use of colour and the evocative power of kitsch are present in some of the most arresting works in Estamos Bien. The Chicago-based artist Yvette Mayorga utilises pattern and decorative form to create statements about identity – a method that recalls the work of the Cuban modernist Amelia Peláez. Works such as The Procession (After 17th-century Vanitas) – In Loving Memory of MM nominally refer to older forms of art but also celebrate abundant shapes and colours, such as shocking pink FIG.4. They are a type of celebratory Latinx resistance to all forms of hegemonic propriety in recent art of the past. Terrill also enlists the communicative power of colour, as well as images of mass produced, fresh comestibles and HIV medication, to critique American consumerism. Each of his works, such as Black Jack 8, includes a muscular Black male, with whom, the artist states, ‘I have had a sexual engagement’ in these ‘scenes celebrating the drugs that have allowed me to be a practicing maricón’ (p.231) FIG.5.

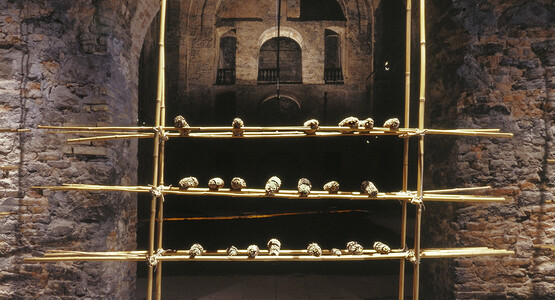

Collective performances and projects play a serious role in the show. For example, the performance collective Poncili Creación, consisting of the twin brothers Pablo and Efraín del Hierro, staged a protest action in San Juan. One brother beat a relentless rhythm on a drum while the other walked and danced in the street, fitted with an outrageous lattice structure including banners ‘filled with the great demands of Puerto Rico in the twenty first century’ (p.203) FIG.6. Shown in the gallery, a video of the performance faithfully relays the potency of this piece to the visitor. Documentation of a much larger public protest is presented in a monumental photograph by Ada Trillo. Taken during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in Philadelphia, the images juxtapose the monument to George Washington and other iconic buildings in the city with the massed participants – in an image reminiscent of some of the most moving Civil Rights era photographs FIG.7.

One of the most disconcerting and provocative pieces is a series of paintings by the Houston-based artist Vincent Valdez called The Strangest Fruit FIG.8. Here, living male figures are painted as lynching victims, shown isolated, without the tree, noose or other details. The artist ‘examines the historic subject of lynchings of Mexican and Mexican Americans in the American Southwest through a contemporary lens’ (p.243). These photorealist works immediately bring to mind not only the historical proximity of the lynchings of Black and Latinx people that occurred well into the 1960s, but makes palpable the constant and immediate possibility of the revival of this singularly horrifying practice in the United States in 2021.

Estamos Bien offers a richer and denser panorama of ideas and images than is possible to suggest here. This review will likely not be the only one to end with words of admiration for El Museo’s curatorial effort but, at the same time, a plea to reinstate the biennial format. The art on display in the Triennial responds to both universal and culturally specific phenomena. As all of the issues confronted here – inequality, violence, suppression of individual liberties, homophobia, transphobia, and so many more – continue to evolve and morph into new areas of concern. These engaging, innovative and at times brilliant Latinx artists will not hesitate to create work that reflects the instantaneous nature of society. Their reactions to both the degradation and exaltation of the world around them would be seen to greater advantage in closer proximity to their creation.