Art writing is in trouble. This is not the usual crisis in criticism – a perceived death of rigour, commitment and judgment connected to the proliferation and expansion of art. It has simply grown apathetic and bloated like the various art worlds it supports, starved of content and determined to avoid defining a cultural or ideological position. This type of writing takes its form in books by jobbing journalists stuck knocking out material for Frieze or Texte Zur Kunst (the latter glued to a cynical form of conservative critique), who want to reinvent themselves as theorists or novelists in order to accrue a serious veneer, or the authority to pen endless catalogue essays that allow commercial galleries to shift work. In the end, this is writing that few will read, it has little critical impact and simply looks bad for dealers and artists if it is not there.

Artists’ writing meanwhile has recently taken an ambitious turn towards mainstream literature. This is interesting because it represents an attempt to escape the myopic ghettos of the many art worlds we inhabit. Since 2014, for example, Fitzcarraldo has boomed with its brand of ‘experimental writing’ and long-form essays. Its aristocratically understated visual identity lends it a certain gravitas, and the publisher is having a significant impact in the wider culture: its authors were Nobel laureates in both 2015 and 2018 and the publisher was recently awarded the ‘Republic of Consciousness Prize’ for Animalia by Jean-Baptise Del Amo. This award is an accolade that celebrates the best fiction from companies with less than five full-time employees, with the small outfit instrumental in supporting writing that blends art and literature.

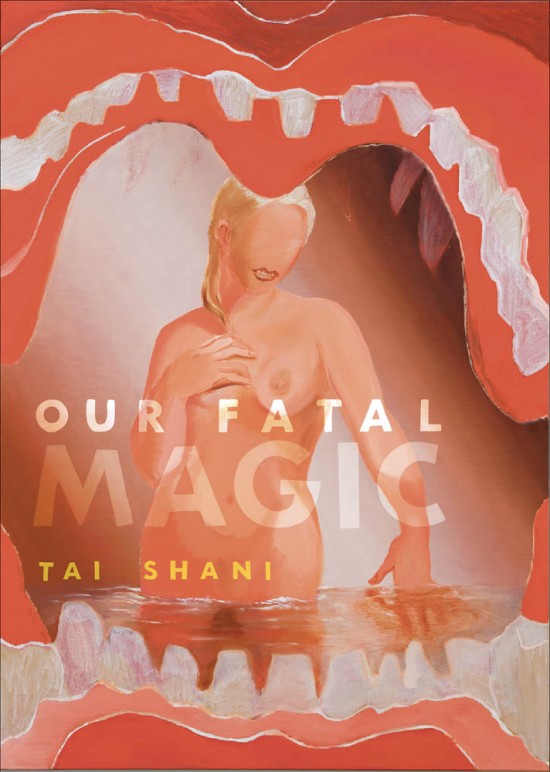

Two new books were born in this context in 2019: Tai Shani’s collection of sci-fi vignettes, Our Fatal Magic, and Ed Atkins’s stream of consciousness prose poem Old Food. The latter, published by Fitzcarraldo, started its life as an installation consisting of video works, wall texts and performance readings. Most notably, it was shown at the Venice Biennale in 2019 (FIG.1; FIG.2; FIG.3), and was read by the actor Toby Jones at Conway Hall, London, in December of the same year.

Atkins’s narrative describes scenarios in an abject English landscape, where characters play and eat among the ruins of their lives. Hannah, who one might describe as the narrator’s main romantic concern, accompanies Granny, who pops up intermittently throughout this hedonistic and grotesque stream of thought. Near the start, we are introduced to the overriding concept of rancid sustenance when the main protagonist comes across a banner reading ‘Old Food’. What follows is an extremely stylish index similar to Viz’s epic list of bodily functions in ‘Roger’s Profanisaurus’, its tragicomic tone reminiscent too of the magazine’s ‘Drunken Bakers’, a pair of hopeless alcoholics who destroy themselves with absolute dedication to the cause. In Atkins’s case, it is food not booze that is the bad ingredient. Add to Viz references to Artaud and Bataille and the linguistic posturing of Clockwork Orange, and the result is an erotic and violent narrative comprising two compadres who eat, fuck and fist themselves to oblivion.

Atkins is a stylish and funny writer. We get glimpses of great turns of phrase, including ‘speech impediment grout’ (peanut butter and bread), ‘spastic veal calves’ and ‘squeaky erasers of hot salty haloumi’. The visual layout of the text also accentuates a chic English literary clang; an elegant right-kind-of-wrongness, with line endings shunted forward unexpectedly in the manner of concrete poetry. If Atkins falls short, it is because he is not nasty enough. In fact, I once heard him described as ‘the new Adrian Mole’, which strikes a chord: here we have Atkins aged thirty-eight and three-quarters, an aspiring poet and writer, or gentleman-thug, full of performative bluster but without the satire on human pretention.

Old Food really gets going towards the end, when time starts to stretch and ‘countless billions’ in the story ‘die of pestilence’. Bleak scenarios of malnutrition are held together with a wistfulness reminiscent of Artaud combined with Edgar Allen Poe and Laurie Lee’s Cider With Rosie. English summers from the 1920s and 1970s are evoked, along with a theatrically cruel and absurd nihilism. Descriptions include those that feed on the blood of animals, and others forced to drink their own urine, recycling it through the body ten times in a row.

At this point the book’s already non-linear time becomes warped and magnified, as vampires crowd the dark ‘spent earth’. Essentially this is a huge recipe (for disaster), written over years that is simultaneously ‘forever’ and an abject ‘non-starter’, in Atkins’s own words. In the same vein that Deleuze viewed Proust – as a ‘universal schizophrenic’, whose paranoiac erotomaniac characters become ‘marionettes of his own delirium’ or ‘profiles of his own madness’ – Atkins’s own fixation is held in his characters’ insatiable desire for death. The text might also be seen as an uncanny portent to the current global crisis, filled as it is with home habits, enforced domestic science populated with leftovers, toilet paper and first-world fretfulness.

Like Old Food, Shani’s Our Fatal Magic is the conclusion of a long-term project. The artist’s five-year multi-form work DC Semiramis, which led to her Turner Prize nomination in 2019 (FIG.4; FIG.5), is based on proto-feminist and feminist literature. Included in this story is Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), which invents a new city without rigid genre roles, as well as Pamela Sargeant’s sci-fi novel The Shore of Women (1986). Whereas information about the timeline of Atkins’s wider project is only briefly set out in his colophon, the long development of Shani’s idea is detailed in a foreword by Brigid Crone. Crone’s text is heroic in nature, which is humorous as it somehow mimics epic patriarchal endeavours, and yet in this it goes slightly too far. Crone’s text is concise, accurate and perceptive, but as a giant theoretical caption for the work it seems perhaps a little too edifying, written as it was before any significant time has lapsed for the work’s historical appraisal.

Nevertheless, the writing itself is a revelation. As a series of descriptive scenarios somehow taken out of time and space, the chapters are sexual and hallucinogenic. The writing style is similar to that of Old Food, and in a section titled ‘The Vampyre’, there is also a concern for the living dead. A passage reads:

‘She is the Vampyre. She lives at the salient threshold of this world in a single frame; the subliminal intervention between here and nowhere. She is lifelessness, but she is not lifeless. She is the shadow. She is the crepuscular dusk lapping at our feet where ever we go.’

It is important to ask what this work achieves. If one of Shani’s (and Crone’s) main questions is: ‘What constitutes the feminine?’, one answer seems to be that the female body represents a collective space. This is figured first through Shani’s female-only city as a metaphorical entity, secondly through an imagined quixotic past and future in the present, and thirdly through the book’s twelve chapters that form another meta-body of text, a holistic or universal unit or being, reinforced by the religious, mythological and magical associations of the number twelve with perfection, entirety or cosmic order. This suggests that Shani’s structure is a satirical take on flawlessness, as the stories explore the infinite sublime of possibility in identity politics, and the delimited nature of identity.

Like Atkins, one of Shani’s concerns is for a different register of time, not only in literature’s past, but also for future speculations about the feminine. Shani’s is therefore a device, like Atkins’s, that serves to radically disrupt the space-time of the present as a political tool. Semiramis becomes an inclusive city of women in a temporal register outside of chronology, a disruption of mechanical time by the nature and rhythm of grass-roots activism. Simply put, Our Fatal Magic is a portal to an alternate world, and Shani’s illustrative attempt at sci-fi might be read as a form of satire.

The work is less convincing when it reaches into outright fantasy. As the artist Martine Syms has argued in relation to Afro-Futurism of the 1970s, which contained elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy and magic realism, such a complete departure from political realities can offer little more than escapism. Syms’s view is that important issues should be grounded in a tangible reality: ‘no interstellar travel – travel is limited to within the solar system and is difficult, time consuming, and expensive’. Shani’s Femino-Futurism falls into the same trap, with real-time activism or a different aesthetic approach (as meta-political methodology) somehow being preferable to her own space-time explorations. There is also something uncomfortable about Shani’s religious references, in that the mystical-temporal catch-all of her universal-utopian narrative holds a form of authoritarianism in its own right. Utopianism is, as many claim, innately a patriarchal construction. Aside from these minor points, Shani’s writing chimes with fifty years of radical feminism and queer theory to problematise totalised subjects of identity.

Both books present an alternative to an endemic form of meta-criticism that pervades the culture of our current art ghetto. Such narratives are one technique for inhabiting the wider world with distinctly durational and equivocal positions, Shani with preposterous – ‘pre’ (past) ‘post’ (future) – bodies and identities in flux, and Atkins through a cataclysmic yet strangely hopeful view of the body in multi-temporal space.