Andrew Kerr

by Jamie Limond

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 15.05.2019

Mist at the Pillars, Andrew Kerr’s 6th solo show at the Modern Institute, Glasgow, invites comparison, judgment and thus, criticism. The Glasgow-based painter makes works that are generally small, frequently on paper, and with layered washes of thin paint. Their quotidian subjects – most often abstracted still lifes – and airy colours give a twentieth-century, British-painting feel. Yet a recurring strangeness holds in check any danger of their sliding too far into Bloomsbury gentility, while the layering of buried forms suggests exploration. Determinacy and indeterminacy are consistently examined.

A telling picture in this respect is titled Stamp FIG.1 (all works 2019). It could depict just that, a small ink stamper resting on a pile of books, carrying with it notions of cataloguing and categorising, while also playing into the show’s questioning of ‘completed’ status, resolution, the stamp of approval. Yet the specific relationship of the stamper to the surface it ‘sits’ on is highly ambiguous, as is its scale; generalised, book-like forms could equally be lines of deep perspective, the ‘stamper’ instead a buoy adrift in a coastal landscape, an inscrutable indicator, bobbing and un-berthed. There are such slippages in register across the exhibition.

The paintings are displayed here in groups and clusters of like, related or apparently unrelated works. The gallery text explains how the artist has recently taken to ‘repeating’ paintings, and these re-done motifs are placed close to one another, or are echoed across the room, punctuated by rogue elements, one-offs. The extensive text goes on to list a host of Kerr’s influences, which invites more than usual licence for comparisons with other artists. Kerr is by turns a Richard Tuttle, a Richard Aldrich, a Robert Ryman. Things are assembled, pinned or glued together or to the wall, merging notions of construction and instability, doubt and authority. Rainbow FIG.2, its marks like impressions or residues, has a mono-print quality resembling the work of the Glasgow artist Lotte Gertz, and so invokes notions of ‘reproduction’ versus original gesture. Similarly, rainbows – fairly common phenomena that appear strikingly singular to onlookers – perhaps speak of paintings as being striking-yet-repeatable phenomena themselves; iterations of potentially hackneyed, but nevertheless arresting, motifs.

The misty pillars of the exhibition’s title FIG.3 are strongly reminiscent of Merlin James’s viaduct paintings, particularly in their exploration of solidity and evanescence. The thinness of paint and support, their itchy abstraction, maddeningly close to representation, puts Kerr close to Tony Swain, while there is an implicit sense of process through the paintings’ layering and revision that is close to Victoria Morton's. All these artists are cited, and the exhibition stresses the importance of Kerr’s Glasgow peers. Indeed, the show questions whether Kerr sufficiently distinguishes himself either from his peers or from the wider field of contemporary painting generally. Do the works become more or less distinct, more or less communicative, more or less exceptional when seen outside of this local context?

Kerr’s candid, even emphatic, referencing of other artists speaks not only of influence and originality among practitioners, but also of the need for due attention to be given to the groupings, allegiances and distinct identities of individual paintings within any practice. The works in the present show frequently extend or mutually support one another, as visual metaphors slide across and between the paintings. A question-mark-shaped motif, perhaps an umbrella or winch FIG.4, haunts the show, as do images of grappling hooks and claws, props that support and suspend. And the metaphors set up are in turn about support, carrying. Bottles become banisters, which become pillars. Yet doubts persist. What, precisely, are the roles of minor or supporting works?

We are left to question our own assumptions of slightness or finish. There is a sense that the evaluation process is ongoing, although production is at a halt. Each work’s status is provisional (comparisons with Raoul de Keyser would be appropriate). Sometimes a work’s apparent meagreness of scale or materials is bolstered by its framing, albeit in frames of thin plywood, semi-transparent paper, or the implied ‘frame’ in one case (Yellow Bands), wherein a work on paper is transposed, at the same size, onto a larger stretched and primed canvas, painted white. The gallery text suggests that the works on canvas are the ‘final’ pictures, but it is not clear what that means precisely, beyond common prejudices about finish, or legitimacy through materials (all works are in acrylic).

Aside from the still lifes of stamps, hooks, books, vessels and trophies, there is a recurring marine theme. Shrimp-like forms parade in The March, while Rocks is a recognisable seascape. And this is perhaps where Kerr’s declared affinities with Prunella Clough are most visible. (A small selection of Clough’s diverse works were shown at the neighbouring 42 Carlton Place gallery across March–April). Kerr’s seaside is like Clough’s, un-pretty, post-industrial; little bits of plastic flotsam are redeployed and scaled-up to the size of a landscape, or estranged in wacky abstraction. The spiral in Kerr’s painting Roll is like a trilobite or a discarded pastry swirl, and The March bears more than a passing echo of Clough’s late 1950s slag heap paintings.

There may also be ritual, perhaps Christian, imagery running through the show: fish, vessel, alcove, arch. A silhouetted angel or gargoyle is suggested in one work FIG.5. Such images might be elaborating on notions of faith and doubt, or on how such differentiated symbolism is highly dependent on context and tradition. Certainly, the central group of pillar paintings carries a sense of druidic rite, the two smaller studies evoking standing stones wreathed with laurel garlands, the ‘mist’ more like smoke or incense than, say, the steam of an unseen train. As with James’s viaducts, these images recall Manet’s The Railway (1873; National Gallery of Art, Washington), in which a girl looks through iron bars, held rapt by the unquantifiable play of light and steam, the relative solidity and insubstantiality of matter. Kerr operates at the unstable end of this spectrum (a Morandi-esque wobbliness pervades). His ‘thinness’ could be seen as symptomatic either of supreme doubt or supreme confidence. But the paintings’ scale and sense of absorption would seem to err more towards a quiet questioning, rumination; gestures may be quick in themselves, yet accrued over time; the paintings are mist-thin or water-thin; wet, settled dry, with the bubbled patterns of evaporating liquid-paint captured on the surface.

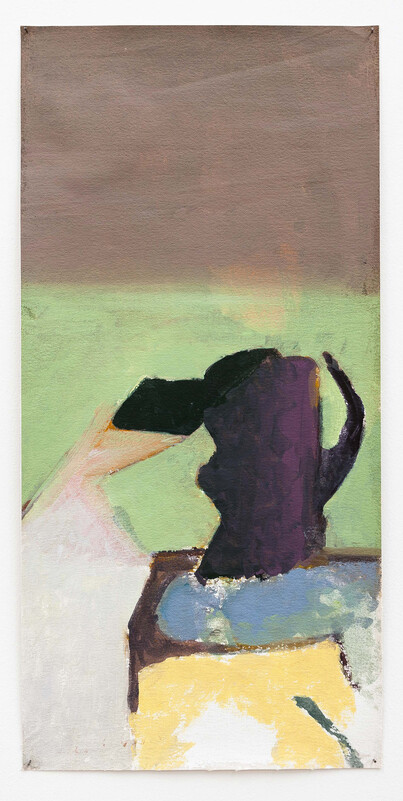

The success or failure of the show rides on whether the works can maintain a distinct identity while playing the game of repeat/reshuffle. It mostly succeeds, but suffers when, as in the series of Yellow Bands, they are too little differentiated. The presentation might have benefited from losing some pictures, while the role of scale in remaking an image is largely unexamined, since most works are of a similar small size. Mist at the Pillars prompts an examination of how we might find excellence in a work; how, broadly, one painting may be demonstrably ‘better’ than another, and how this quality is tied to the painting’s distinctiveness. Is Kerr’s painting of a Small Jug [fig.6], for example, exceptional among small-jug paintings (the hidden, pursed-lip profile on the left of the jug like a representation of Zephyrus, ‘blowing’ and sustaining its own form)? Kerr’s pictures FIG.6, with their visual slips and ambiguities, their pictorial probing, suggest that a painting's distinction lies not in its subject alone, but in its active interrogation of that subject.