Communist witches and cyborg magic: the emergence of queer, feminist, esoteric futurism

by Amy Hale • Article commission

by Amy Hale

Reviews /

Film and moving image

• 21.05.2021

In his book Psychedelic White, the scholar Arun Saldanha characterises the normative story of the psychedelic experience as typically that of a man: a white man, undergoing a deep, transformative experience, often facilitated in some way by a cultural ‘other’.1 People from ‘exotic’ – read non-white or indigenous – cultures and women serve as agents of change for the seeker; they possess an earthly or otherworldly essence that the man is attempting to integrate into his development. If women feature at all they support the male journey as nurses, mothers, lovers, demons or goddesses. As Mariavittoria Mangini has argued, women’s psychedelic histories are rarely considered, especially those concerning themes of personal development and discovery.2 Current attempts to highlight women’s contributions to psychedelic culture and its emergent industry are primarily focused on healing and wellness, creating narratives of wholeness and overcoming trauma rather than a search for enlightenment. Can a symbolic feminist reading of the psychedelic experience disrupt male-centred narratives, which are often structured as Joseph Campbell inflected heroic journeys?3

In Kim Hewett’s essay ‘Psychedelic feminism: a radical interpretation of psychedelic consciousness?’, she argues that the psychedelic experience, regardless of the participant, is essentially feminine in nature:

Psychedelic experiences offer infinite possibilities for libidinous fusion: with other humans, nature, spirits, ancestors, and the cosmos. Altered states of consciousness challenge our culturally constructed concepts of the body, individuality, gender, time, and every other bounded category structured by linear human thought. Discussion of consciousness, like the body, is always mediated by text and yet cannot be contained by it. A foray into expanded consciousness is a plunge into the realm of the symbolic feminine which will always be in excess of language.4

This is the world of Tai Shani’s The Neon Hieroglyph. The artist's previous works have established her as a maker of unconventional feminist mythic histories and magical stories. DC: Productions (2014–19), a series of tales, films and installations conceived over a five-year period, was Shani’s reimagining of Christine de Pizan’s radical The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) FIG.1. The project takes the audience to future worlds through alternate histories and intimate interior spaces, endeavouring to circumvent the patriarchal language and structures that restrict lives and imaginations. The Neon Hieroglyph, her first online project, extends this social commentary and develops the visual language and mythos of an occulted, feminist, psychedelic vernacular.

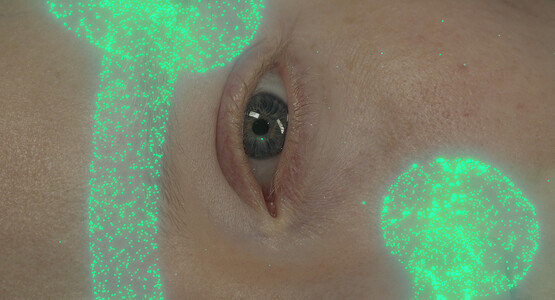

Shani envisions The Neon Hieroglyph as a collection of projects that emerge from nine fragmentary tales featuring ergot (a fungus that grows on rye) as a psychedelic catalyst. The work debuted in its initial online form in March 2021 at Manchester International Festival’s Virtual Factory as nine short interconnected films. Scripted by Shani, each instalment explores this enduring yet underacknowledged psychedelic, immersing the audience in mythic and historical settings associated with incidents of ergot poisoning or consumption. Our guide in these filmic journeys is the actor Molly Moody FIG.2, who is compellingly real and unreal, with an accent deliberately engineered to be both marked and unmarked, simultaneously evoking a particular place and no place at all, or perhaps every place at once. The haunting score is written by Shani’s long-time collaborator, the composer Maxwell Stirling. Together with Moody’s narration, it provides an evocative continuity to the visually diverse vignettes. The films slide between the micro and the macro, exploring caves and planets, spores masquerading as nebulae, phosphenes functioning as universal visual codes, ice cream sundaes and darkness FIG.3 FIG.4.

For Shani, ergot evokes a different, feminist history of psychedelics. Unlike ayahuasca or peyote, the consumption of ergot is not typically linked with ritual ingestion; it happens more by accident than by design. Within the context of women’s health, ergot has been more conventionally described as an abortifacient and a migraine treatment. Its unofficial effects, however, are linked to tales of underworld initiations, witches, astral travel, demons, dances of possession and the communal folding of reality – all themes that are knotted together in Shani’s work. Although The Neon Hieroglyph points to specific histories and locales, the temporal narrative is effectively disjointed, simulating time travel through the psychedelic eyes of the narrator.

In episode 1, the journey starts in the French village of Pont-Saint-Esprit, where an ergot outbreak poisoned 250 people in August 1951. It was blamed on ‘cursed bread’: ‘We had eaten the poisonous bread, milled from contaminated rye.’ / ‘Do you too feel manic when you swell and are about to burst? We ask the dragon, tiger, paisley, whey clouds’.5 Episode 6 FIG.5 draws on tales from the Italian island of Alicudi where, according to local legend, women baked ergot-laden bread, keeping islanders in a visionary state for 450 years: ‘This bread is a placebo; the bread is a spaceship’. / ‘This bread is real, it kills heroes. This bread is a starmaker of collected stardust’.6 In Episode 5 Shani’s tale of initiation conveys the communal underpinning of shared experience through time, as she relates a colourful, hallucinatory version of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Kykeon, the barley wine ingested during the rites in ancient Greece, is believed to have included ergot as a component, leading to visionary states: ‘Down, Rharian field, ellipses, carnivores, swanskin and poplin. Consumed spoiled grains fatally atrophies, in muted purple, the useful limbs and tessellates fractals that bridge into worlds unknown where our grasp on a telepathic, interdependent language is sensual’.7

For Shani, the psychedelic state breaks down both the structures of the universe and oppressive social conditioning. She is interested in the ways in which psychedelic spaces can drive new visions of society; an important feature of The Neon Hieroglyph is the notion that psychedelic experiences can create freer mental spaces, unfettered by normative ideas about society and culture. As a result, people are able to experience imaginative states liberated from the influence of language, where new collective futures can emerge:

That sense of collectivity was the main thing I wanted to explore, and ergot seemed like a very interesting conduit for me to address how the more metaphysical questions, or the immaterial mysticism, or the fantastical dimensions of [how] our lived experience or culture might be put to use in a more direct, social-materialist way.8

Shani’s ideal psychedelic figure is not the enlightenment seeking hero. Instead, she is the witch, who, in the Aeolian islands, where Alicudi is located, is a liberatory figure. Shani explains:

The figure of the witch is a psychedelic one, the witch represents a threshold between the natural and supernatural, between the material and metaphysical, like acid, ergot, mescaline etc. [She] is an agent that has both a material and immaterial life, a threshold between two realms. The witch is also the vessel that contains the changing attitudes to excess, from her porosity to the divine, which becomes her permeability to evil. The witch is the human embodiment of chaotic wickedness and dark powers, and powerful she is but she is also a wrecker of civilization and morality.9

Shani’s excessive Italian witch, encountered in episode 6, is a Robin Hood figure, redistributing food during nocturnal flights. Yet this emphasis on collectivity is not a hippie vision that draws on the aesthetics of an idealised antimodern past. In Shani’s work, time collapses: past and future are experienced on a cellular level. Her indebtedness to science fiction is clear and The Neon Hieroglyph engages with more than a touch of the speculative future. Shani’s imagery allows the audience to explore the monstrous and the permeability of the body as both the experience and objective of psychedelically induced union: ‘We exchanged spectacularised ocular fluids continuously, mouth to mouth, watertight, the screen and us, hewing grooves for the fluids to douse and drain, to and from each other’ FIG.6.10

The fragmented structure and pulsing viscerality of the films eerily establishes Hewett’s concept of the feminist psychedelic:

The symbolic feminine encompasses what has been excised as unnecessary, a threat, or excess: irrationality, the unconscious, emotion, imagination, play, mystery, and pleasure without purpose or closure. Feminine discourse is similar to the Bakhtinian carnivalesque that subverts the established order and revels in the messiness of the ‘grotesque body’ that is always in flux and cannot be contained.11

Shani creates imaginative spaces for exploring social transformation, inhabited by the fluidity of feminine excess and unboundedness, transcending confines of language, making way for visions of new, communal relations. Yet for all the dark chthonic power of The Neon Hieroglyph, Shani’s urging toward the collective is marked by the revelation that all beings in the universe already exist in a state of connection and interdependence with all other things:

We are phytoplankton, greenly photosynthesize into photosensitive green life givers. We would be eternally green communists, eternally horizontal, eternally porous, eternally communing to collaboratively compose the epic unsung anthem of the unbroken cycle of our interdependency. A fragile ecology in the powerful movements of astral dust.12

The world of The Neon Hieroglyph is fleshy, it oozes and dreams, merges and spills over, envisioning futures we as yet have no names for. It is generated in a space that lies beyond words, ultimately envisioned as a radical undoing. Yet The Neon Hieroglyph leads the audience to a space of connection, inviting them to personal and communal discovery: ‘We, us and our could be a cosmic community that connects time and space’.13

Tai Shani: The Neon Hieroglyph

Manchester International Festival: Virtual Factory

31st March–18th July 2021