The art of thought: Katie Paterson’s ‘idea-images’

by Lisa Stein

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 04.03.2019

When the American educator Abraham Flexner founded the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, in 1930, his guiding principle was the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. The Institute, which he envisioned as ‘a haven where scholars and scientists could regard the world and its phenomena as their laboratory, without being carried off in the maelstrom of the immediate’,1 became one of the world’s leading centres for ‘curiosity driven basic research’ and home to such distinguished thinkers as Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer and Erwin Panofsky. In an essay published in Harper’s Magazine in October 1939, Flexner presented the case for basic research, maintaining that ‘curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful, is probably the outstanding characteristic of modern thinking’ and that ‘institutions of learning should be devoted to the cultivation of curiosity, and the less they are deflected by considerations of immediacy of application, the more likely they are to contribute [. . .] to human welfare’.2 Focusing on experimental science and mathematics, Flexner argued that pioneering inventions were often wrongfully attributed to one individual when in fact they spanned many decades of research conducted ‘without thought of use’ and that the greatest discoveries were made by men and women who sought, first and foremost, to satisfy their curiosity.

This approach lies at the heart of Katie Paterson’s practice. The work of the artist from Glasgow, currently on display at Turner Contemporary, Margate, is based on an ongoing series of thought experiments. Published in a book to accompany the exhibition, Paterson’s Ideas are short texts relating to nature, geology and cosmology.3 Reminiscent of Yoko Ono’s ‘instruction paintings’ from the 1960s, which ‘not only delegated responsibility for the realisation of the work to the viewer but [. . .] also overturned the conventional requirement that art should take physical form’,4 Paterson’s Ideas are works of art intended to inhabit the imagination FIG.1. While some may never come into physical existence, a selection has been realised in a series of installations that are presented across four gallery spaces.

Paterson’s most recognisable work is suspended from the ceiling in one of two larger rooms. Totality FIG.2 is a disco ball whose individual, mirrored tiles depict phases of nearly every solar eclipse ever documented. The effect of the large sphere as it slowly turns, projecting hundreds of overlapping crescent shapes on the surrounding walls, floor and ceiling, is dizzying. An automated grand piano playing nearby heightens the effect; there is something unsettling about its seemingly familiar melody. For Earth–Moon–Earth (2007) Paterson used a radio communication technique also known as ‘moon bounce’, which relies on the propagation of radio waves directed via reflection from the surface of the Moon back to a receiver on Earth. The familiar composition playing in the gallery space is Beethoven’s Quasi una fantasia – more commonly known as the Moonlight Sonata – which, having been reflected off the uneven lunar surface, now contains gaps and absences. Here the moon’s craters and shadows are rendered audible.

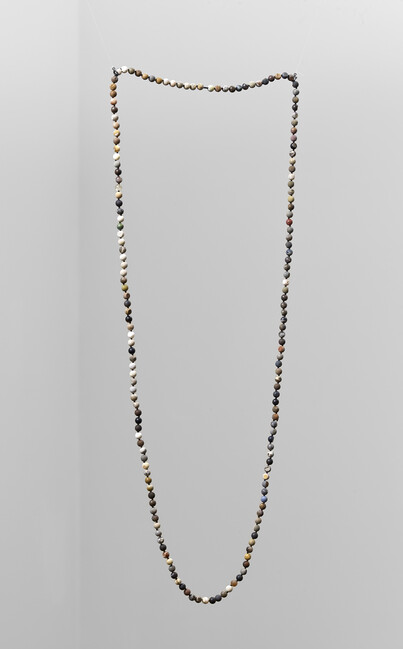

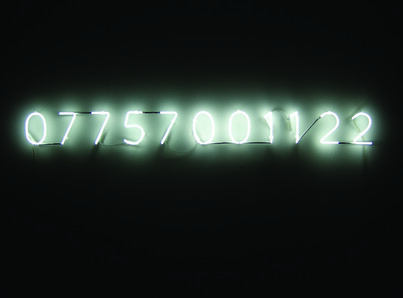

Such works as Totality and The Cosmic Spectrum FIG.3, a large colour wheel painted in the shades of the universe throughout its existence, spinning fast enough for the different colours to blend, create a sense of bewilderment not unlike the kind experienced by observing natural phenomena. Similarly, the sheer scale of The History of Darkness FIG.4, Paterson’s ever-expanding archive of slides recording the darkness of the universe, each one containing handwritten information about the distance from Earth in light years, puts the human life span – itself a starting point for many of the artist’s projects – into perspective. Although Paterson’s art is often discussed in the context of Kant’s dynamical or mathematical sublime there is also an ethical dimension to her work, which communicates the interconnectedness of all things in the universe. Fossil Necklace, for example, which comprises 170 fossils carved into small spherical beads that chart the development of life on our planet FIG.5, and Vatnajökull (the sound of), for which Paterson established a phone line to a melting Icelandic glacier via an underwater microphone submerged in a lagoon FIG.6, highlight the disastrous effect humans have had on the planet in the relatively short time they have inhabited it. Indeed, the glacier has since disappeared and all that remains are archived recordings and a phone number, now out of service, installed on the gallery wall FIG.7.

While Paterson’s œuvre certainly appeals to the senses – sight, sound and even smell – the viewer’s perceptual engagement with her work does not prevent their imaginative engagement with the ideas underlying it. On the contrary, by using familiar objects, sounds and technologies the artist enables the viewer to engage with the invisible and the unfathomable. It is precisely the beauty of such works as Fossil Necklace and Vatnajökull (the sound of) – the colours and patterns of the individual, meticulously carved fossils and what would have been the soothing sound of trickling water – that intensifies the sense of loss the viewer experiences when confronted with them. However, Paterson’s presentation does not always live up to her ‘idea-images’: the effect of Ara, a string of festoon lights matching the relative brightness of stars in an unspecified constellation, is underwhelming. Hanging high above the heads of visitors in the brightly lit gallery space the installation is hardly ‘immersive’. Similarly, Paterson’s idea of merging the colours of the Los Angeles cityscape with the stellar landscape of the Milky Way arouses the viewer’s curiosity, and yet the resulting photograph, Colour Field, has no real visual impact. But to dwell on the aesthetic qualities of these works is perhaps to miss the point, especially in the context of Flexner’s approach. Paterson’s series of thought experiments exemplify what he referred to as the ‘unobstructed pursuit of useless knowledge’, for her Ideas are not conceived with the intention of creating a physical work of art, but rather embody the art of thinking itself, giving rise to questions of epistemological and moral significance.

What is arguably Paterson’s most ambitious work is represented by two small posters on the gallery wall: for Future Library the artist planted a forest in Norway in 2014, which will supply paper for an anthology of books to be printed one hundred years later.5 Each year Paterson commissions an author to contribute to the project, and these texts, by writers including Margaret Atwood, David Mitchell and Elif Şafak, will be held in trust, unpublished, until the year 2114. Conceived as an abstract thought experiment – ‘A forest/of unread books/growing for a century’ – Future Library has taken on immense proportions, addressing such themes as materiality, impermanence, authorship, sustainability and technology. Whereas many of her works require the trust of the viewer, in this project it is the artist, Paterson herself as well as one hundred authors, who must relinquish control and put their faith in a trust whose objective is to ‘compassionately sustain the artwork for its one hundred year duration’.6

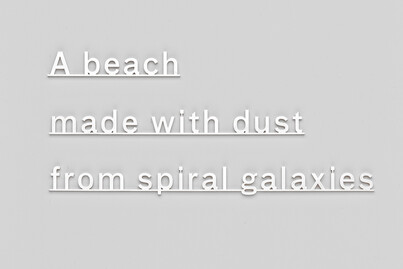

With views over the Kent coastline, Turner Contemporary provides an apt setting for A place that exists only in moonlight, which combines Paterson’s works with a selection of paintings by JMW Turner FIG.8, whose interest in geology, chemistry and astronomy led him to conduct restless experimentation. His small, abstract works – some consisting of no more than two or three brushstrokes – are displayed among Paterson’s installations in the first two galleries, while notes from his experiments are exhibited in a separate room alongside writings by Mary Somerville and Caroline Herschel, the first two female members of the Royal Astronomical Society. Unlabelled, Turner’s paintings, which are echoed in Paterson’s palette of light pastels combined with the deepest, darkest brown and black, complement her Ideas, particularly those that adorn the wall in the form of barely legible texts cut from sterling silver FIG.9 with the potential of becoming labour-intensive works of art. Together, Paterson’s minimal texts and Turner’s atmospheric washes of paint form quasi-constellations, revealing the various ways in which we can come to ‘know’ something. And for Flexner it was precisely this type of restless experimentation – aesthetic, intellectual or artistic – from which, ultimately, ‘undreamed-of utility’ might be derived.