Magdalene Odundo

by Marina Vaizey

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 04.04.2019

The Journey of Things is a heartbreakingly beautiful collection of objects brought together by the intelligent, widely curious and omnivorously observant ceramicist Magdalene Odundo, who has curated the show. The titular phrase can be taken literally, as many of the objects gathered at the Hepworth Wakefield originated thousands of miles away or thousands of years ago. The title can also be interpreted on another level: much of the art on view is held in public collections and is therefore divorced from the domestic, utilitarian and religious contexts from which the objects emerged. The exhibition juxtaposes fifty of Odundo’s own vessels with almost one hundred contemporary and historic pieces, including pottery, sculpture, dress and textiles. The result is an enthralling and instructive anthology. Within a few steps, one can see objects from New Mexico, the Congo, Nigeria, Colombia, France and Ancient Greece: this is a worldview impervious to categorisation.

Odundo’s own journeys give context to her wide-ranging eye. Born in Kenya, she moved to Britain in 1971 to attend art school in Cambridge, where she studied commercial art. She decided on ceramics as her chosen medium several years later, when studying in Farnham at the West Surrey College of Art and Design, now the University of Creative Arts – of which Odundo is currently chancellor – and then the Royal College of Art, London. In 1974, encouraged by Michael Cardew, she studied at the Pottery Training Centre he had founded in Abuja, Nigeria, and her course was set. Clay, she reminds us, can be made into anything: vessels, containers, votive objects, burial urns and buildings; it is a material that is ubiquitous, even ordinary, and hardly costly; it is, she has said, ‘the material that has informed the history of mankind’.1 Odundo travelled to study her medium in Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda. Having gained numerous professional qualifications and taught extensively, notably in Farnham, she is eloquent about the importance of looking at art of all kinds.

With ease and disarming grace, Odundo manages to break down Eurocentric hierarchies in relation to the geographic origins, materials and functions of objects, views that have been cemented over several centuries and which are embedded almost subliminally into Western culture. The display is enhanced by the superb installation designed by the architect Farshid Moussavi, who deploys platforms of varied height and uses a range of dappled greys for the walls and bases. The design gives plenty of room for Odundo’s own work, occasionally gathered in self-contained clusters FIG.1, or else interspersed in visual dialogue with the other objects. It is another way of looking at past and present, with the only constant characteristic being the captivating and absorbing beauty of the work on view. Improbably, a phrase from Yoko Ono springs to mind: ‘beauty is what you love’.2

The groupings of Odundo’s ceramics, threaded through this anthology, include gracefully bulbous vessels of fired clay that contain nothing but air and are eminently embraceable. The curved and rounded shapes suggest the human form, and perhaps above all the roundness of advanced pregnancy, but labelling most of her work Untitled, Odundo leaves room for visitors to project their own semblances and resemblances onto the works. As fragile as these objects may be, they are made of a material that survives millennia. Some of them are gigantic and look as though they might be utilitarian but they are not. The burnished and oxidised or carbonised terracotta gleams, coloured in variations of orange and black. These ceramics honour the quality of their material. Odundo often needs multiple firings to achieve her smoothly glistening, tactile surfaces.

Although the exhibition includes works by famous artists that resonate with Western viewers, including those by Degas, Henry Moore, Giacometti, Hans Arp and Picasso, there are also large numbers of anonymous pieces (or as the label charmingly has it, ‘unrecorded maker’) from across millennia and continents. Earthenware pottery and Congolese textiles, with their seductive textures and abstract patterning, complement Odundo’s own early ceramics, which are more apparently functional as receptacles than her later work. Nearby there is a host of teapots by such artists as Cardew, Ian Godfrey and Walter Keeler. As objects these teapots can seem subtly eccentric and unexpected: the graceful curve of a handle is almost ethereal compared to the robust spout.

In one grouping, bottles and jugs from various tribal cultures, including those in Ghana and Uganda, are shown alongside a bottle by Lucie Rie from the 1970s and a Cypriot earthenware jug that is nearly four thousand years old. In another, a nineteenth-century fertility doll from the Asante culture, Ghana, nestles in a corner with a late sixteenth-century portrait of an elaborately dressed and bewigged Tudor woman in court dress (1590) and a vivid patterned green dress by Yinka Shonibare FIG.2. Shonibare’s Jane Morris (2015) explores the cross-currents of cultures: the Dutch waxed and printed fabric uses a technique learnt by Europeans from Indonesian batik, but was later imported back into Africa from the Netherlands; the title, meanwhile, refers to William Morris’s wife. Typically for this fascinating compilation of objects, Shonibare’s art questions the nature of sculpture, and is itself a multilayered object with several cultural references across time and geography.

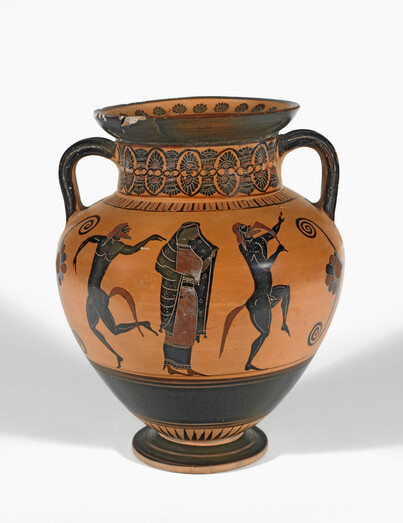

Dance, movement and gesture are explored many of the objects FIG.3, including in the decorations on a Greek amphora from the 6th century BC FIG.4, Degas’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen FIG.5, a dancer by Rodin (c.1911) and Bernard Meadows’s bronze fiddler crab in full scuttle (1980). Reduction and refinement may be found in Cycladic sculptures, a Henry Moore head (1926) a burnished and carbonised vessel by Odundo, typically Untitled FIG.6, as well as a still-life by Giorgio Morandi (1954) and Wedgwood-inspired jasperware cups by Rie (1963).

As curator and artist, Odundo has precisely summed up why we want and need to see: ‘Objects hold the knowledge of our history’. Through her selection, Odundo shows how the past informs the present: Peruvian stirrup cups, often shaped like birds or human faces, have been a direct inspiration for the nineteenth-century vessels of Christopher Dresser and Odundo alike.