Forests of the mind: spectres of deforestation in contemporary English aesthetics

by Laura Ouillon

by Anna Campbell

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 10.03.2019

George Shaw’s paintings glow with otherworldly light. There are flaming dawns and overcast afternoons, wet pavements and bright spring skies. There are lamps in dark windows and dappled forest floors. Their hues are vivid, saturated and glossy to the point of banality. Yet catch them out of the corner of your eye and they sing like colours never seen before in painting.

In many ways, they are just that. Shaw’s medium of choice is Humbrol enamel – a utilitarian paint traditionally found in aeroplane modelling kits. With this humble hobbyist’s material, the artist crafts elegiac hymns to the Tile Hill council estate in Coventry, where he grew up. In his mid-career retrospective at the Holburne Museum, Bath, Shaw’s visions shine out of the dimly lit gallery like beacons. Farrow & Ball coats the walls: ‘a corner of a foreign field’ indeed.

The exhibition is downsized from its first instalment at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. Selected highlights from the past two decades follow a loosely chronological narrative. No. 57 (1996; Royal College of Art, London) depicts Shaw’s childhood home: a modest terraced house still inhabited by his mother. Works from his ongoing cycle Scenes from the Passion chart local haunts across the changing seasons, bestowing a near-spiritual sense of revelation upon desolate pubs and garages FIG.1. His Ash Wednesday paintings, inspired by James Joyce, capture the estate at different times on a single day FIG.2. Although Shaw describes himself as a lapsed Catholic, the message is clear: ‘Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return’.

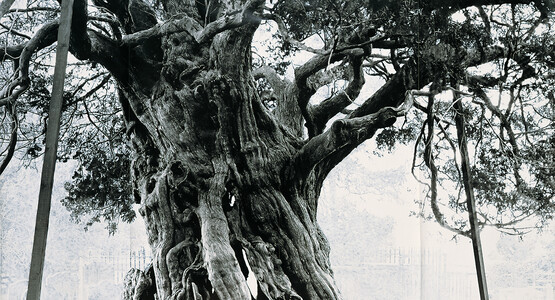

Built in the 1940s and 1950s, Tile Hill was once a utopian dream. Nestled in the Forest of Arden – the setting for Shakespeare’s As You Like It – it set a new benchmark for public housing, offering a pioneering union between modernist architecture and nature. As the exhibition progresses, this history plays an increasingly poignant role. Shaw captures the decay of the estate: the graffiti, demolition sites and uprooted trees. In Every Brush Stroke Is Torn Out Of My Body (2015–16) FIG.3, painted as part of his residency at the National Gallery, London, the woods begin to bleed. In The Call of Nature (2015–16) FIG.4, the artist himself makes a rare appearance, urinating unceremoniously against a tree. As the reverence of his early works begins to unravel, so too does the exhibition’s narrative: wall texts are increasingly repetitive, cycling somewhat laboriously through the same stories and analyses.

At the centre of this downward spiral, however, stands a bastion of youthful hope. Spare Time (2006) FIG.5 is an installation of drawings created during idle moments, whose subjects reflect Shaw’s teenage infatuations. Based on printed source imagery, and rendered with immaculate precision, they move seamlessly from religious iconography and pornography to David Bowie, Francis Bacon and Frankenstein. It provides a fascinating insight into an artist who first encountered the work of Caspar David Friedrich on a CD cover. These studies match the optimism and loving scrutiny of his early work; collectively, they offer a glimpse of the figures who haunt his vacant landscapes.

The exhibition’s accompanying catalogue represents the most comprehensive book on Shaw to date. Mark Hallett offers a detailed survey of his practice, structured around key series and early exhibitions. Essays by Catherine Lampert and David Allan Mellor discuss his influences and imagery, while Thomas Crow discusses his drawings. A conversation between Shaw and Jeremy Deller yields some lively anecdotes, wending its way through art history, literature and pop culture. Perhaps the book’s most enlightening observations are to be found in Eugenie Shinkle’s essay on the relationship between Shaw’s paintings and post-war architectural photography. As well as shedding light on early representations of Tile Hill, it offers crucial context for an artist whose works rely heavily on his own snapshots, stored by their thousands in old shoeboxes.

Nevertheless, the book suffers from some of the same problems as the exhibition. Rather like Shaw’s practice, which returns periodically to certain landmarks, much of the text covers similar ground. The challenge of distilling clear thematic strands from his meditative œuvre leads to a slightly inflated emphasis on biographical details, which recur like signposts across the essays. The book’s promise to contextualise Shaw’s work in the history of British landscape painting, meanwhile, remains somewhat unfulfilled. Surely Lucian Freud, who turned his own piercing gaze to the ‘wastegrounds’ of suburban London, deserves deeper discussion. So too does David Hockney, whose treatment of light quivers in Shaw’s Humbrol elegies, and whose paintings of felled trees in Yorkshire are practically contemporaneous with Shaw’s Woodsmen FIG.6.

Perhaps the most notable absence from the discussion here is Peter Doig, Shaw’s former teacher at the Royal College, and a clear influence upon his work. Despite the book’s title, curiously reminiscent of Doig’s 2013 exhibition No Foreign Lands, there is little acknowledgement of this lineage. Doig’s depictions of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation – another modernist utopia submerged in nature – are mentioned only fleetingly. Fruitful comparison could equally be made with Shaw’s contemporary Hurvin Anderson, another student of Doig, who shone a similarly complex light upon neighbourhoods of Trinidad. And while critics have typically been quick to distance Shaw from the Young British Artists, they too might offer alternative possibilities for historicisation. Tracey Emin spun autobiography into art, Gary Hume made his name using functional gloss paints and Damien Hirst probed religious metaphors. Do Shaw’s Scenes from the Passion owe nothing to this world? The artist, after all, began his career filming medical procedures in hospitals: ‘I think if I’d carried on with that, I would have been a YBA!’, he admits. 1

One senses, however, that this is said in jest. Shaw’s practice, although rooted in contemporary concerns, is not fundamentally provocative. It comes close in Someone Else’s House FIG.7 – a work that simultaneously opens and closes the exhibition – whose fluttering England flag might be read as a judgment on Brexit. Yet while Shaw acknowledges the significance of the vote, the painting ultimately transcends socio-political commentary. Perhaps the blood-red cross of St George might be better understood as a crucifix; perhaps the rumpled fabric is merely a sign of life, as dynamic as his rippling bark or falling blossom petals FIG.8. Poverty tourism was never part of Shaw’s agenda: these are emotive portraits of home, as timeless as they are timely. It may not be Rupert Brooke’s halcyon dream of England. Then again, as the sun rises over the forest, maybe it is.