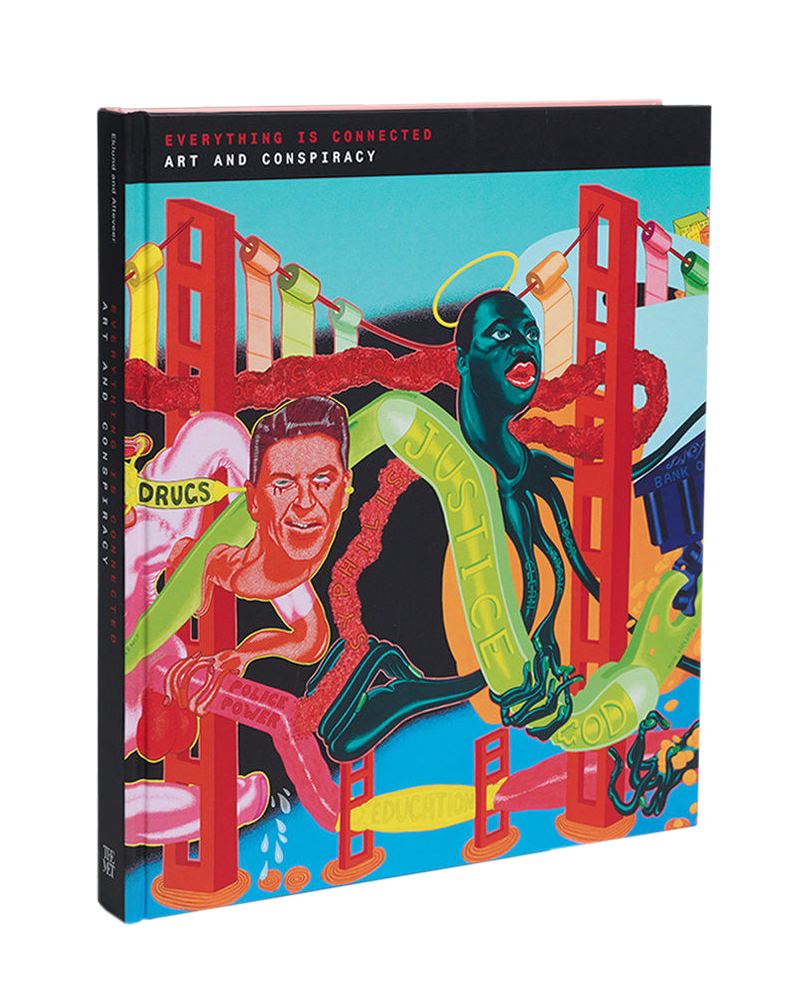

A scandal in Bohemia (Art and Conspiracy in New York)

by Robert Slifkin

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 08.10.2018

With reports in the media of both old-fashioned espionage and high-tech surveillance, alongside accusations of the news itself being falsified (at the behest of elaborate and impenetrable agencies within the avowed ‘deep state’), the exhibition Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy could not arrive at a more propitious moment. While contemporary affairs inescapably inflect the seventy works arrayed on the fourth floor of the Met Breuer, New York, the show looks back a little further to what might be seen as a prehistory to our current sense of paranoia and dread. Assembling the work of thirty artists mostly working in the United States from 1969 to 2016 – from the election of Richard Nixon to that of Donald Trump – the exhibition effectively surveys a range of strategies artists have used to visualise, comprehend and occasionally undermine the elusive nexus of corruption, power and lies that seems to thrive in modern, technologically mediated societies.

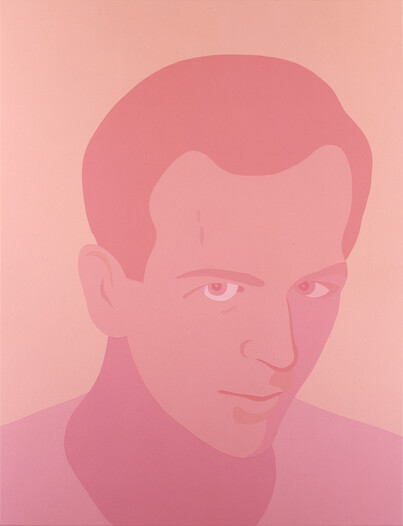

The exhibition presents events such as the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal and the Iran-Contra hearings as examples of what the historian Richard Hofstadter memorably described as ‘the paranoid style in American politics’, a thesis that elaborated an American tradition of populist suspicion of government. But it is the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 that serves as its modern emblem, if not its origin. (In fact, Hofstadter first presented his thesis in a lecture given during that year.) The assassination of JFK appears throughout the show like a leitmotif, first announced in Wayne Gonzales’s large pendant portraits of Jack Ruby and Lee Harvey Oswald FIG.1, which greet visitors coming out of the elevators. With their respectively monochrome palettes of green and peach and their mostly factureless surfaces – punctuated by linear ridges of acrylic where the artist taped off unmodulated sections denoting shadows and contours – the paintings subtly hint at the cover-up that has rendered these two men as ciphers for all things conspiratorial.

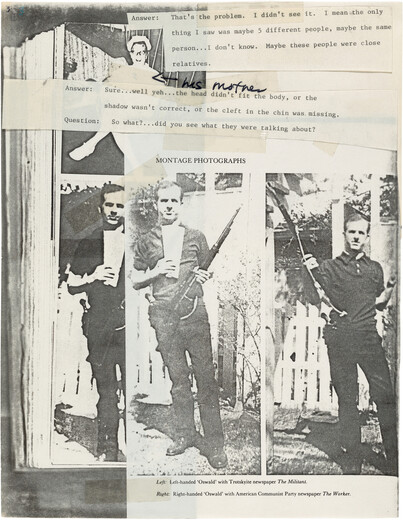

Oswald reappears in Lutz Bacher’s faux-evidentiary series of photocopy collages from 1976 FIG.2. These contain fragments from a type-written transcription of an interview between the artist and an anonymous interlocutor that addresses the assassin’s slippery identity. Bacher employs an off-hand and quasi-documentary aesthetic that became increasingly prevalent in the wake of 1960s conceptualist practices. Numerous artists began to take on the roles of detective or criminal, often deploying willfully amateurish photographic techniques to record ephemeral actions and leaving behind ‘clues’ from a past performance. Bacher’s work seems to express an identification, even empathy, with the alleged villain, in particular Oswald’s capacity to remain unknown despite extraordinary public scrutiny.

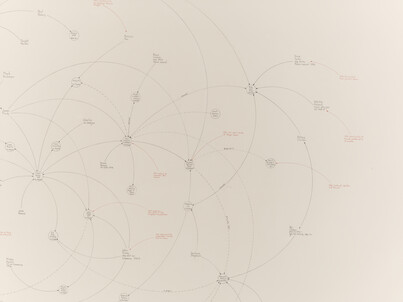

Even in those works that seem most dedicated to justice, such as Hans Haacke’s unyielding grid of thumbnail photos and captions documenting exploitative real estate practices, the convoluted conspiracies are given a degree of formal coherence and even beauty that surpass any accusatory revelations. Two further examples of aestheticized data are Mark Lombardi’s delicate diagrams of the intricate – and intentionally confusing – networks of money and politics FIG.3 and Öyvind Fahlström’s information-packed and colourful map of the world, in which handwritten statistical information largely determines the contours and size of the countries. Both of these endeavours to apprehend the Byzantine matrices of power take on the semblance of the sublime.

Unsurprisingly, webs are a recurrent theme throughout in the show, sometimes appearing quite literally, as in Jim Shaw’s The Miracle of Compound Interest (2006), where a massive red spider’s web covers an idyllic small town depicted on a theatrical backdrop. In other instances, webs are suggested through all-over gestural compositions, as in the oozy, black armature that obscures the words ‘Government and Business’ in an untitled painting by Mike Kelley. Vibrant, hallucinatory conjunctions of body parts and building fragments (notably that of the World Trade Center) create their own all-over rhythms in paintings by Sue Williams FIG.4, whose amalgamation of hidden iconography and biomorphic abstraction provides a chilling update to abstract expressionist angst. Along with the Day-Glo nightmares of Peter Saul FIG.5, including a sketch from 2006 depicting Hitler’s brain, still alive and taking a shit, these works express through abject imagery a sense of indignation at the unjust machinations of power as well as the necessary dynamics of the discharge of suppressed information.

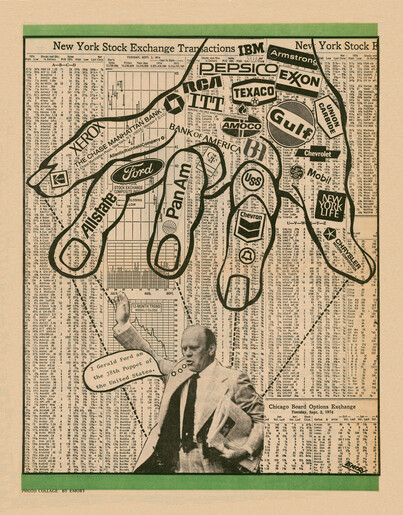

These more fantastic renderings of the conspiratorial temper of modern society point to a central tension of the exhibition. As Salvador Dali recognised in the 1930s, a ‘paranoiac’ artistic method dedicated to uncovering latent messages can bring with it a productive confusion between fact and fiction.1 Accordingly, there is a discernible surrealistic spirit in many of the works on view, largely overshadowing what could be seen as a more hard-headed tradition of speaking truth to power. This latter approach is exemplified by Emory Douglas’s trenchant illustrations for the radical publication The Black Panther FIG.6, which portray the various ways that the mainstream establishment of American society operates to undermine the powerless. Similarly direct works include the strident posters produced by the collective ACT UP that declared previously undisclosed statistics about the AIDS crisis, and Jenny Holzer’s enlarged reproductions of redacted government documents related to the military invasion of Iraq in 2003. In these works the bold and compelling visualisation of suppressed information is offered as evidence. In the case of Holzer’s monumental canvases and LED displays – as well as Cady Noland’s tombstone-like sculptural monuments to newspaper articles – the works’ physical massiveness seem to ensure their preservation into the future, where they may serve as testimony to crimes that remain unpunished.

Art has long served the purpose of visualising unseen powers, and in doing so often takes an antagonistic stance towards institutional authority, visible or not. Everything is Connected makes the compelling case that such an approach became crucial in the media-saturated age augured by the assassination of JFK. Beyond its undeniable relevance to the scandalous abuse of power of our contemporary moment, the show offers something of a shadow history of Postmodernism. It presents art’s increasing engagement with the dynamics of representation not as some academic exercise or illustration of theory, but rather as a vital and necessary means of understanding a world in which interconnectivity and treachery seem to exist in tandem. As expert scavengers and artificers, artists have a privileged perspective on these secretive matters. Whether these skills remain viable in an age when conspiracy has gone mainstream remains an open question, and one which haunts the show.